Ali the Man

Special | 1h 4m 43sVideo has Closed Captions

A Q&A with Ken Burns, Jesse Washington (moderator), Rasheda Ali Walsh, and Howard Bryant.

In this virtual event series, filmmakers and special guests explore Muhammad Ali: The Man. Conversations on Ali is presented by PBS and The Undefeated, and features Ken Burns, Jesse Washington (moderator), Rasheda Ali Walsh, and Howard Bryant.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate funding for MUHAMMAD ALI was provided by Bank of America. Major funding was provided by David M. Rubenstein. Major funding was also provided by The Arthur Vining Davis Foundations,...

Ali the Man

Special | 1h 4m 43sVideo has Closed Captions

In this virtual event series, filmmakers and special guests explore Muhammad Ali: The Man. Conversations on Ali is presented by PBS and The Undefeated, and features Ken Burns, Jesse Washington (moderator), Rasheda Ali Walsh, and Howard Bryant.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipMore from This Collection

Conversations on Muhammad Ali has Ken Burns and special guests exploring Muhammad Ali's life and legacy. The hour-long discussions feature clips from the four-part series.

Ali, Activism & The Modern Athlete

Video has Closed Captions

A Q&A with Raina Kelley (moderator), Malcolm Jenkins, Claressa Shields, and Ken Burns. (1h 5m 4s)

Video has Closed Captions

A Q&A with Ken Burns, Justin Tinsley (moderator), Ibtihaj Muhammad, and Sherman Jackson. (1h 4m 57s)

Video has Closed Captions

A Q&A with Ken Burns, Lonnae O’Neal (moderator), Janet Evans, and Todd Boyd. (1h 10m 6s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship- [Narrator] He was bigger than boxing.

- [Ali] I am the greatest!

- [Narrator] He was larger than life.

- His magnetism just was amazing.

Who is this guy?

- He was a revolutionary.

He was a groundbreaker.

- Ain't nobody gon' stop me!

- [Narrator] Ken Burns captures an intimate story of victory, defeat and determination.

- The price of freedom comes high.

I have paid but I am free.

- [Narrator] Muhammad Ali.

Tune in or stream.

Starts Sunday, September 19th at 8/7 Central, only on PBS.

- Good evening and welcome to the first event in our discussion series, "Conversations on Muhammad Ali presented "by PBS and ESPN's The Undefeated."

I'm Sylvia Bugg, Chief Programming Executive at PBS.

For more than 50 years, PBS has been proud to serve as America's home for documentaries; providing our audiences with impactful and inspiring films that cover a wide range of topics and perspectives.

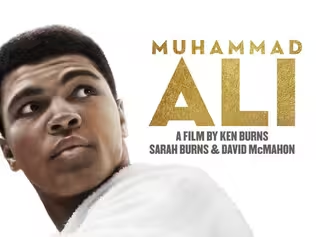

This September, PBS is delighted to present the latest from Ken Burns, Sarah Burns, David McMahon, and their team; a four-part documentary series on the global icon, Muhammad Ali.

This series take us deep into the life of one of the most indelible figures of the 20th century, showing us the true nature of the man who called himself "The Greatest" and proved it.

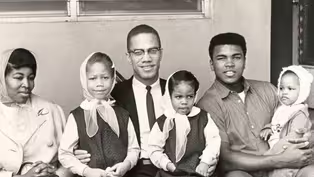

Today's discussion, simply titled "Ali: The Man," will explore the humanity of Muhammad Ali as a loving father, an advocate for peace, and an inspirational voice of pride and self-affirmation in the black community.

In just a few moments, we'll show you the introduction to the film.

Then, senior writer for The Undefeated, Jesse Washington, will moderate a conversation with co-director Ken Burns, Muhammad Ali's daughter, Rasheda Ali, and author and sports columnist, Howard Bryant.

Thank you for joining us this evening and please enjoy this evening's discussion.

And don't forget to tune in to the premiere of "Muhammad Ali" on September 19th at 8:00 PM Eastern Time on PBS - Can I have some of your corn flakes?

Oh, I don't want none.

I won't take none, I won't take any.

I won't eat any if you don't want me to.

Oh, look at the pretty horsey!

Is that a white horse?

See?

Stand up, look over there.

Stand up, you gotta stand up (indistinct).

(indistinct) What?

(crowd cheering) - My earliest memories that I can think of as a child with my father are walking through airports and being in crowds, and feeling the vibrations of people's clapping and shouts in my chest.

And just looking at my dad, like "Who is this person?"

And it was all the time, anywhere we went.

"You're the greatest, we love you!"

And the clapping and "Muhammad!"

- Ali Bomaye!

Ali Bomaye!

- [Crowd] Ali!

Bomaye!

Ali!

Bomaye!

- We now think of Muhammad Ali as this vulnerable guy, lighting the torch in Atlanta and everybody on the globe loves him.

Black people like him, white people.

He's a universal hero, almost in a religious way, like the Buddha.

But when he was in the midst of his career, and not just in the early bit, he was incredibly divisive.

- Boo, yell, scream, throw peanuts, but whatever you do, pay to get in.

- People hated him, whether it was along racial lines, class lines, Vietnam lines, political lines, religious lines, or they just couldn't stand him.

And people, of course, had the opposite and this was, "I loved him!

"Loved him!"

(upbeat music) But you had an opinion about him.

- (indistinct) Look how pretty I am.

The long, trimmed legs, and the beautiful arms, and a pretty nose and mouth.

I know I'm a pretty man.

I know I'm pretty.

You don't have to tell me I'm pretty.

- [Ali V.O] I'm cocky, I'm proud.

- You never talk about who gon' stop me, 'case ain't nobody gonna stop me!

- I say what I wanted to say!

It ain't no more big niggas talking like this.

- He was a pioneer.

He was a revolutionary.

He was a ground breaker.

A guy known simply as "The Greatest."

- I am the greatest!

- [Ali V.O] I've rassled with alligators, I've tussled with a whale.

I done handcuffed lightning, and put thunder in jail.

You know I'm bad!

I can drown the drink of water and kill a dead tree.

- This will be no contest.

- [Ali V.O] Wait 'til you see Muhammad Ali.

- To have that chutzpah and to be a black man in America was just outlandish.

- "Muhammad" means "worthy of all praises;" and "Ali" means "most high."

- And I just don't think I should go 10,000 miles in there and shoot some black people that never called me nigger.

I just can't shoot 'em.

- I always wonder why Miss America was always white, Santa Claus is white, White Swan Soap, King White Soap, White Cloud tissue paper, and everything bad was black.

Black cat was the bad luck.

And if I threaten you, I'm going to blackmail you.

I said, "Mama, why don't they call it whitemail?

"They lie too."

- I loved being around him.

I love being around Muhammad Ali.

- You gon' float like a butterfly and sting like a bee.

Rumble, young man, rumble.

- The price of freedom comes high.

I have paid but I am free.

- [Announcer] The winner and still the heavyweight champion of the world.

- [Narrator] He called himself "The Greatest" and then proved it to the entire world.

He was a master at what is called "the sweet science;" the brutal and, sometimes, beautiful art of boxing.

Heavyweight champion at just 22 years old, he wrote his own rules in the ring and in his life, infuriating his critics, baffling his opponents, and riveting millions of fans.

At the height of the Civil Rights Movement, he joined a separatist religious sect whose leader would, for a time, dominate both his personal life and his boxing career.

He spoke his mind and stood on principle, even when it cost him his livelihood.

He redefined black manhood, yet belittled his greatest rival using the racist language of the Jim Crow South, in which he had been raised.

Banished for his beliefs, he returned to boxing an underdog, reclaimed his title twice, and became the most famous man on earth.

He craved adulation his whole life, seeking crowds on street corners, in hotel lobbies, on airport tarmacs, everywhere he went, and reveled in the uninhibited joy he brought each adoring fan.

He earned a massive fortune, spent it freely, and gave generously to family, friends, even strangers, anyone in need.

"Service to others," he often said, "is the rent you pay for your room here on earth."

Even after his body began to betray him and his brain had absorbed too many blows, he fought on, unable to go without the attention and drama that accompanied each bout.

Later, slowed and silenced by a cruel and crippling disease, he found refuge in his faith; becoming a symbol of peace and hope on every continent.

"Muhammad Ali was," the novelist, Norman Mailer wrote, "the very spirit of the 20th century."

- I've always wanted to be one black one who got big or your white televisions, on your white newspapers, on your satellites, million dollar checks, and still look you in your face, and tell you the truth, and 100% stay with and represent my people, and not leave them and sell them out because I'm rich, and stay with them.

That was my purpose.

I'm here and I'm showing the world that you can be here and still free, and stay yourself, and get respect from the world.

- Welcome, welcome, welcome everyone, I'm Jesse Washington from The Undefeated.

Really pleased to be here today to discuss this wonderful new film, "Muhammad Ali."

I'd like to introduce our panelists.

First, we have the director himself, Ken Burns; the prolific documentary filmmaker whose credits are far too numerous to name here.

But he is bringing us this new look at the life and meaning of "The Greatest of All Time."

I think it's important to note that there's a lot of talk about GOAT this and GOAT that these days, it's become almost a cliche.

We've got herds of GOATs everywhere, but there is only one "Greatest of All Time" when it comes to athletics in this country forever and ever, and that is Muhammad Ali.

Ken Burns, welcome and we're glad to have you.

- Thank you, Jesse.

It's great to be working with you and The Undefeated, and on behalf of Sarah Burns and David McMahon, who are the two co-directors and those two are the writers, we're so grateful to be part of this.

Thank you.

- Thank you.

We also have Howard Bryant here with us, the journalist and author of nine books.

Most recently, his most latest book, is "Full Dissidence: Notes From an Uneven Playing Field."

And Howard is a longtime columnist at ESPN, has worked at many other newspaper outlets in this country.

All of the best ones, if I may say.

And is also a newly minted contributor to Meadowlark Media, where we will be seeing more of his work in a variety of other forms and platforms.

Howard, welcome.

- Thank you, Jesse.

Good seeing you again.

- Good to see you too.

And also we have Rasheda Ali, an author, speaker, humanitarian, and daughter of Muhammad Ali.

Rasheda, it's great to have you here today.

- Hi Jesse, thanks for having me.

I'm honored.

- You're very welcome.

We're honored to be here with you.

So wonderful film, Ken.

It was great to see an early version of it.

I was enraptured and riveted by your work.

And the first thing I'd like to ask you is that you're approaching this giant, so much has been written, so much has been said.

Films upon films, books upon books.

What is it that you wanted accomplish when you started out with this film, and now that it's finished and about to be released on September 19th on PBS, what is it that you want people to learn from this film about Ali?

- Oh, that's a complicated question.

Thank you, and Sarah and Dave would probably have different variations of that question... Or the answer to that question.

You know, we're drawn to him.

He's a spellbinding, hugely important person in the history of the United States.

It's not just sports.

I'm drawn to him personally.

In the course of my professional life, I've gotten to know a lot of amazing Americans.

Only two others come to mind that have a sense of charisma, a sense of purpose, a sense of being able to embody us in all of our contradictions.

One of them is Abraham Lincoln and the other is Louis Armstrong, and Muhammad Ali is in that select group of someone who's just personally touched me.

I'm not talking about where he is placed in the pantheon of sportspeople.

I agree with you Jesse, he's at the top.

There are a lot of films about him.

There are a lot of really, really good films about him but I think what we wanted to do is do a true biography from his boyhood in Louisville, in Jim Crow America, up to his death not too many years ago by Parkinson's and everything in between.

So not just a couple of fights, there's two dozen that are treated in detail, not just his difficulties with the United States over the draft and induction, not just this or that, but the whole thing, and try to get a sense of who the whole man is, warts and all, as the introduction, I think, suggested.

And it would be so presumptuous of any one of us, Sarah, Dave, or me, to say this is "What you should take away."

We just want to tell a good and complicated story that is able to contain contradictions.

But at the end, you begin to realize how extraordinarily gifted this man was, not just at his chosen profession, but at the profession of being a human being.

You know, I've said this a few times; It's always really good if you leave this planet being the most beloved person on this planet.

And that's what all of us should be tilting towards if we can.

He did, and he was, and I'm interested in who that is.

I'm interested in it, warts and all.

But at the end of the day, it's about love.

That's what he understood.

And there are people who spend a long time trying to get at that, he got at it.

He understood it.

And I'm so happy that Rasheda is here because she carries not only whatever genetics, the bloodline, but she also carries this sense of love and spirit.

And having Rasheda close to me is like he's still here in a way.

- Absolutely.

So Rasheda, I was struck as I watched the film, and as I thought about our world today, how we still... Islam has not truly been accepted in America.

I was struck by the fact that so many people mispronounced the word "Muslim" in the movie, or mispronounce the word "Islam," you know?

And so, what is it that you might hope or think that America can learn about your father and his relationship to his faith from this film?

- Thank you so much.

First of all, I wanna thank you so much, Ken for those beautiful words.

And thank you, Jesse.

I think my dad, he led by example.

So he was a great role model, not just for us but for the whole world, because I think when my dad did was he wanted to urge us to be the best version of ourselves and to push ourselves to become better than who we think we are.

So he adopted this faith and he was...

It was full circle.

He really was passionate about joining the Nation of Islam, and it gave him so much courage and bravery at a time where his people were being lynched and killed, and segregation was going on, and there was so much hate against our people.

He felt that this religion was the one that was going to give him the power to believe in himself and his people.

And so, he did all that thinking of his people.

His people were always something that he had in mind whenever he did things because anything he did, he empowered them.

And so, as the religion evolved, he became even more spiritual as a man because this religion, Islam made him not only strong mentally, but it gave him the courage to do things that I don't think he normally would have been able to do if he didn't have his religion backing him up, so to speak.

So he felt like.... And there are clips in this film that I've never seen before, and I've seen probably thousands in my life.

I mean, I've just over and over.

But there were really interesting clips and I know most of you have already seen the clip where he says I'll face gunfire without denouncing my faith and my religion.

So if we can all adopt his passion and his love for faith and in God, or some higher power, I think we'll all already be that much closer to getting what we're all seeking, and Ken said it so well, and that's love.

I think that's what makes the world go round.

My dad adopted a religion that was not socially accepted.

It's still not.

So I think our passion to be able to become role models for those who still have Islamophobia on their minds, we have to remember that people are looking at us as Muslim all the time, trying to find out, when are we going to make a mistake?

And when are we going to commit a crime?

So I think my dad felt his responsibility as a Muslim was to become a role model for people who are Muslim, but not only that, but for people who are trying to find themselves, trying to find their faith, and I think he did a very good job of that.

He wasn't perfect, as we know that.

(indistinct) humanize my dad.

In this film, he wasn't perfect.

He was human, just like all of us.

- Jesse, you're muted.

- Thank you.

Those contradictions are fascinating.

How a man can emanate so much love and still do what he did to some of these people in the ring is one of the most interesting journeys that there is in the field.

Howard, I wanted to ask you, there can never be another Ali because of who he was and what he did at the time that he did it, in the tumultuous 1960s, when black people, as a whole, in America, were taking control of their destiny.

And so, we've just, in 2020, came through another tumultuous and incredibly moving and...

Emotional upheaval and a racial reckoning, awakening, something along those lines.

We're still processing what it was.

Ali doing what he did when he did it... And now, it's fashionable for athletes to be "aware" or "activists" or all this kind of stuff.

And a lot of these young athletes who probably do care about racial justice don't know Ali's story.

So what lessons do you think Ali and what he did, today's athletes should really take and learn from and use as they try to use their platforms as he used his?

- Yeah, well for me, I just feel like the biggest thing, when I think about Muhammad, I always think about risk.

And risk not to himself, but the type of risk that is very much prevalent today when it comes to professional athletes, and that is you are asked to make a deal when you're a pro athlete.

And that deal is to really separate yourself from your own people.

You're constantly being asked not to advocate for black people.

You're constantly asked to hang out with a different crowd or you know that in the culture, being what it is today, simply advocating for or supporting black people is a political act.

You know that because the minute somebody says something that's in support of black people, it becomes a news story.

Why is it so controversial?

Why is this such a risk?

Why is it such a... Why are you putting your entire career in jeopardy simply by saying, "I support the people of Ferguson or Baltimore or whatever"?

So I think that's one of the things that needs to be done, that maybe athletes have a great shot of doing right now, which is demystifying the idea of supporting black people, right?

I mean, why is this the defining thing that can threaten your livelihood?

And so, I think that's one of the biggest things for me when I think about athletes today.

I think the secondary thing is the idea of the comparison.

You're not going to compare yourself to this man and it's not because he was so great, even though he was; the real reason is is because what he did and what Jackie Robinson did, and what so many before us did, made it unnecessary for you to duplicate what he did.

And I think that's the road, when you think about the Colin Kaepernicks, when you think about LeBron James, and you think about Serena Williams, or whoever else is out there today, doing their thing, their paths are just different from his.

And you don't want his path.

You do not want the entire weight of the federal government and its people to come down on you.

You don't want what he went through.

And if you have to go through what he went through, that says so much more about what little progress this country has made than it would say about him.

- Man, thank you.

That's so accurate.

So Ken, I'd like you to setup this next clip that we're going to watch, and not to step on your toes here but it was one of the most meaningful moments of the film for me.

And really, I was sort of vaguely aware of it, as much as I've read and seen about Ali, but it packs such an emotional wallop for me.

So what does this next clip that we're about to see?

- Well, thank you.

Two of our secret weapons in the film are here with us this evening, Howard and Rasheda, and they're wonderful.

One of the others is a man named Michael Bentt, who's a heavyweight fighter who helps interpret mid fights.

He's mainly, almost his entire presence, is within the fights to help us perhaps some of us who don't understand it and find it just brutal, understand what it's about.

So this is 1966.

He's been the champ for two years.

He's announced when he won the championship that he is a Muslim.

It's caused him lots of problems.

He's had his license revoked in some places in response.

He's now said he is not going to be inducted into the United States Army, and he's having a hard time finding fights.

He has to go to Canada, he goes to Europe, and then he comes back and he has a fight.

And that's basically what we're going to show you, is this fight.

So please roll the clip.

- [Narrator] After four fights abroad, Ali's promoters had finally managed to secure an American venue; The Astrodome in Houston, Texas.

A brand new and first-of-its-kind domed stadium, dubbed "The Eighth Wonder of The World."

Ali had agreed to fight Cleveland "Big Cat" Williams, an army veteran who had once been shot by a police officer during a drunk driving arrest.

Williams had knocked out 51 of his 71 opponents.

It would be the largest audience for an indoor boxing match in history.

- I think his masterpiece is with Cleveland Williams.

That's Picasso, right?

That's Baryshnikov, right?

That's Miles Davis.

He throws like a 10-punch combination, he's going back with his man.

Now look, I don't know how to define that.

I'm not a scientist, but like that kind of artistry will never be seen again.

When he did that, it looked effortless, and it looked like he came out of the womb doing that.

- [Narrator] Introducing a new move he dubbed "The Ali Shuffle," he peppered Williams with jab after jab, as the Big Cat struggled to land a single punch.

Ali floored his challenger three times in the second round.

"It was a two-fisted assault "of vicious effectiveness," wrote frequent critic, Arthur Daley, who declared that Ali had won over all the doubters.

A minute into the third round, the referee ended the fight.

(crowd cheering) - [Announcer] (indistinct) - Wow, wow.

I mean, so aside from the physical display there, I'm going to give them a little more context for the audience for this clip.

In the lead up to this fight, Ali had recently embraced the Nation of Islam and had changed his name to Muhammad Ali, and this boxer refused to call him by his name.

And throughout the whole fight, Ali is tagging him, and tagging him, and saying, "What's my name?

"What's my name?"

I found it rather resonant the victim there had a perm in his hair, which is a sign of really of us being brainwashed to want to be more like white people.

And then another really subtle thing in that clip was after they called the fight and Ali went back to his corner, he turned over his shoulder and gave this man a look of utter domination and contempt.

And it was just like...

It gave me chills to see it.

So, "Oh, you're not going to use my name, Muhammad Ali?

"You're going to call me Clay?

"Boom, I'm punching in your face.

"You can't do anything about it.

"Now, say my name."

I mean, it was just so powerful to me.

And it gets us to the Nation of Islam, which was a driving force, an overriding presence in Ali's life, and really depicted in great detail, and historically accurate detail, painful detail, in this film.

And there's a lot about the Nation that is problematic.

The historian, Gerald Early calls it a cult.

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar says it's not true Islam.

And yet, it helped to give us the great mindset and everything of Muhammad Ali.

And I did not know, Ken, that Elijah Muhammad, the leader of the Nation of Islam, gave him that name.

Everyone else was "Something X" or "This X."

So Howard, I would like to ask you, what would Ali have been without the Nation of Islam?

Specifically, that brand of black Muslim?

What would Muhammad Ali have been?

- Well, I think that's a great question, but I would always step back when I think about Muhammad and I would ask, "What would he be without Malcolm X?"

I mean, that's the first connection.

And to so many people, it was... To so many black people, it was an articulation.

It was an attempt to recognize that something's not right here, in terms of what I'm being taught.

There has to be a counter to what I'm being taught because what I know in front of me is not what I feel.

I remember when I was in high school, my mother gave me a copy...

I didn't even know she had it.

She has a first edition copy of "The Autobiography of Malcolm X."

And I was like, "Where did this come from?"

It was like in the living room and she gave it to me.

And when you open it up, she... My mother as a 17 year old; all of these sentences are underlined, underlined, underlined, and that's what I think about when you think about Muhammad.

There's the articulation.

"I get you," right?

"I understand you, I feel you.

"This is exactly what I see."

And I think that when you think about... You look at the clip with Cleveland Williams; here's a guy whose hair is comped and he's talking about respect.

And so, what the Nation did for so many black people was to give us an outlet to say what you're feeling is not preposterous, and what you're feeling is real, and we're going to try to give you some form of roadmap to what we think your true self is, to what you know your true self is.

Because even if it's not this, you know it's not what you're actually living in the United States.

- I think Howard's right.

The courage part of it is so interesting, that you said earlier.

And while the Nation of Islam was a kind of classically American hybrid of stuff and had lots of corruption at its core, it did offer an alternative narrative against the old slave narrative, one of the ones, and it was liberating for this young man and he was able to transform it.

And where Malcolm X, who was excluded from it, was headed both politically and then spiritually is where Muhammad Ali also got to.

And Rasheda says this in the film, the fighting is just one aspect.

He just happened to be doing that.

He happens to be greatest athlete.

But it's amazing that this is about, as he says over and over again, freedom, and the way he found the path to freedom was by accepting this new narrative, this new story of oneself and one's possibilities that the Nation of Islam offered.

- Yeah.

Rasheda, what are your perspectives on the Nation of Islam, both as a presence in your father's life and the criticisms that have been leveled against it in the film and elsewhere?

- The Nation of Islam is not true Islam.

Of course, my dad realized that later, when he adopted orthodox Islam.

But at the time, it was important because it really allowed my dad to face all of the issues that was going on in his life.

Remember, he grew up in Louisville, so that's the Jim Crow south.

So segregation was worse in the South than anywhere else.

He felt, in a sense, like what he did for the United States, winning a gold medal, didn't mean anything.

So the Nation was very important for him at that time because it allowed him to face what was going on in his own hometown, as well as the rest of the world, head on.

So the Nation was important, even though it isn't true Islam.

The ideals was important because it really made daddy understand the importance of being... And Malcolm mentioned that too, is that if you can brainwash someone to hate themselves, that's the worst crime you can do.

And that's what my dad was really trying to allow people to realize, is that as he got more and more recognition and fame, he used that to help his people get out of the situation that they were in.

And so, he did that by saying, "I'm beautiful, I'm great.

"I'm so pretty."

That's something that African-Americans...

It seems like a small thing to do, but for an African-American to say on national TV, "I'm so pretty, I'm great," that was unheard of back then.

And so, he even got a lot of backlash from African-Americans who were also athletes and were saying, "just be quiet."

So my dad was really, in a sense, telling our people "Wake up.

"We can be beautiful.

"We can be proud "and we can get what we want."

So that was the importance of my dad and the Nation.

- Yeah, so much of this is liberation.

When you think about the broad definition of that word, it's liberation.

When you're black, you're taught that you're ugly.

When you think about it, when you grow up, and we all know it, right?

Growing up, even growing up around the way, when black people make fun of each other, our humor is based in making fun of how you look.

Always making fun of how you look.

And he was one of the people... Where do you think "black is beautiful" comes from?

It was the counter to this, to say, "Look, there's another way here."

And our humor is rooted in it.

When you look around, you walk into a store and you look at all the magazines, who's on the cover?

You're not on the cover.

These standards of beauty, they're not you.

Everything about it is not you, right?

You're taught completely to dislike yourself.

And so, as much as the Nation liberated a lot of black people in terms of trying to find a pathway that eventually, in Kareem's case, in Malcolm's case, in Muhammad's case, got them to Orthodox Islam, it also gave you a pathway to pull yourself out of this idea that "I'm not worthy in the white world," that it gave you something to look at that you could be proud of.

And that's one of the things that when we looked at Muhammad, that was the thing that he gave everybody.

He made you feel like you are as beautiful as he was.

- Unless your name was Joe Louis.

Unless-- - and Joe Frazier.

I was gonna say-- (speaking over each other) - What's really ironic about that is that all the things that Muhammad gave us, he used against Joe Frazier.

And the cruelty, He knew what he was doing with Frazier.

I mean, we all knew it and you watch this.

And over time, as you get older, especially the first fight, it was essentially two black men pitted against each other, but one was supposedly representing "White America," and that was Frazier, and he's from North Philly.

So the psychological battle between those two and the cruelty, I hate to say it because Muhammad was everything to me, but the psychological cruelty on someone that he knew was not at his intellectual level as well sold a lot of tickets, but caused a lot of pain as well.

Those fights were real.

And when you watch those fights, and which is why I can keep talking about this forever, Ken, you watch those fights, you can feel black America right there.

You feel all of it.

I mean, right in your face, it's just so powerful.

I watch Ali fights just for fun, 10, 20 times a year.

Let's just go...

Even the second fight, I'll watch that one too.

- Yeah, and he also used that tactic, these inter-black conflicts against George Foreman and set himself up as the black man.

He always set himself up as the black man and would diminish these others, his opponents' blackness, or exaggerate their blackness in order to disrespect them and things like that, and it was... And at the end of the film, he says that he regretted it.

And so, he knew he was wrong.

Ken, do you think that this is... And you're very faithful to telling the story and not putting your finger on the scale, your thumb on the scale, one way or another.

But one thing that really struck me was how young he was when he developed his identity, and young men are headstrong and brash, and plunge forward without considering the full ramifications of their actions.

Do you think that these cruelties that he perpetrated on his opponents were strategic, come from avarice, trying to make more money, fame, attention, some of the above?

How would you analyze that?

- It's a good question.

It was important for us to show everything.

I think we live in an unfortunate culture where everything is on or off, good or bad, and no life is like that.

And our notions of heroism are so limited.

We think a hero is perfect and lament that we're in an age where no heroes, but in fact, heroism is about the negotiation, even the war, between a person's strengths and their weaknesses.

This was not a good side.

Todd Boyd says in the film, "He's using his his power there for evil "and not for good."

But most of the time, it's for good, and it's complicated.

It is strategic and yet, I think he doesn't know.

But let's, remember when you bring up the young man this is a person who, very early in life, understood that he had some mission, he had some purpose.

You don't start boxing for a few months and call yourself "The Greatest" when no one even thinks that you are that, and then make yourself that, and keep yourself that over time, and bring a larger message of love.

So, to me, this is a classic hero's journey.

This is a...

There are lots of dragons to slay and as we know, we're our own worst enemies.

He was his own worst enemy in lots of ways, as we are, all four of us, our own worst enemies, and I think that was an important part to share.

And I was so happy that this beautiful woman here who carries the spirit of her father understood that you couldn't tell it with just only the icing on it.

It had to have complexity and depth, as he did because you can't then emerge from it without appreciating what he went through.

The kind of sacrifices, the risks, as Howard said, that he took, they're unbelievable.

And when something turned out good for him, legally, for example, people say, "Well, is this restore your faith?"

And he just turns around, as if he was talking today, and he said, "Somebody's going to get killed by a cop, "someone's going to get beat up by a cop.

"This is it.

"This was a good decision for me "but it doesn't end it."

And so, there was always a purpose.

He loses to Frazier after belittling him and saying he's going to win with all the confidence, drove white America crazy.

A lot of people were for Frazier just to shut him up, and Frazier, in a way, did, and his post-fight response about his responsibility to people to show that life will bring this... You'll lose someone you love, you'll lose a job, you'll lose a title, and you need to get back up, it can't defeat you.

You cannot understand.

It's the parallel of what Howard was saying about "beautiful."

The parallel to that was a kind of empowering spirit, that this world will throw you a lot of difficult things and I will show you, you can get through this.

So he is as magnificent in defeat as he is in victory.

And we saw the clip where it's Baryshnikov.

it's Miles Davis, it's Picasso.

And that fight with Cleveland Williams is in it... Jesse, just to set you right, that is not the fight, which is "what's my name?

It's another fight that's coming up in that that episode, in which he has been consciously belittled.

I think the important thing about Cleveland "Big Cat" Williams is that he's shot by the police.

This stuff has been going on well before Rodney King, well before Muhammad Ali, well before Emmett till, well before Jack Johnson, well before anything.

It's a 402-year old disease, and it's a virus that's infected our story, and Muhammad Ali intersects with that in powerful ways.

- Yeah, I wanted to throw one quick thing out there to that too, Ken, when we talk about the liberation of this and what Muhammad was saying; It's also, he was liberating athletes because to Jesse's point, ballplayers were supposed to be grateful.

Ballplayers, the first thing about a ballplayer, you call the owner of the team "Mister."

They still do it today.

You win a game and you say, "Thank you," and you're deferential to the reporters, you're deferential to the fans, you're deferential to everybody.

And he was the first guy out there who really took control of his own narrative and understood that "no, no, no, I'm the show.

"You're coming here to see me.

"And what that does is that gives me power."

And Henry Aaron was very similar to that, where he realized that, "If I'm here, you have to listen to me."

And the number of black athletes at that time who were frightened because of what he was doing in terms of that liberation...

There was another generation who said, "Yeah, I want to be just like him."

- Rasheda, what were the most emotional moments of this film for you?

- Well, I cried throughout.

There was some.... Well, most...

There were just tears of joy because it was great to see my dad.

And then, the times where he was...

There was a part in the clip where he was kissing me, or my twin...

I have a twin.

So I look and I'm like, "I'm not sure if that's me or Jameela.

"I'm not sure."

But he was kissing him one of us, me or my twin, and he was like, "Don't you know your father's... "Do you know your daddy's the greatest?

"Do you know your daddy's the greatest?"

My whole face, I just...

I never saw that clip before.

And for daddy to be like, "Did you know your father's the greatest?

"He's the greatest all the time."

I just started crying.

- It's a home movie for you.

- It was like a home movie.

It was like... 'Cause I've never seen that before and I was like, "Oh my God, I've never seen that.

"That's me!"

And it was a time where I didn't really remember because most of my time I remember my dad were Parkinson's.

Because we grew up with the divorce and everything, we didn't grow up with seeing my dad every day.

So to see him interacting with us and with the wagons in Deer Lake, Pennsylvania, I just got some really great memories that just started to rush through my head because they were good times for us, as kids, because we were with our parents.

And we were on this great training camp, and we watched our dad train, and it was just a fun time for us.

But for us, he wasn't famous, he was just our dad who just took us on pony rides and was just being a dad.

- This is what we wanted to do.

The whole film starts with a very long sequence about stealing a bite of cornflakes.

There's not a parent in the world that doesn't know what that kidding is with a toddler, and it was our way of saying, "Okay, okay, we'll get to the boxing.

"Okay, we'll get to the conflict.

"We'll get to this.

"But this is a person who loves other human beings, "and he particularly loves his family, "and he particularly loves his girls."

And it was important to move that from its placement way up in episode three and move it back to the very beginning of the film, and say... Let's just start with something like, "Look over there, I'm going to steal your corn flakes."

- Good call there, Ken.

- Great call.

It was really beautiful opening.

I just immediately started crying as soon as I saw Miriam and my dad just playing around.

I never saw that either.

Again, we're seeing footage I've never seen and it's really taken me back.

It's good memories.

- Our fourth producer, Stephanie Jenkins, and the team of people who look for stuff; the reason why these films take four, five, six, seven years to make is because we want to do the deepest possible dive, possible and make sure that it's not an additive process, but it's subtractive.

We collect hundreds of hours and then say, "Okay, we love that, "but it just doesn't fit."

And the clip we're going to show right now, Jesse, if I can segue into that so we don't run out of any time, is not too much after the other clip but he's refused induction, he's delayed some stuff by changing his draft board from Kentucky to Texas, but he's...

When he's finally inducted, he refuses induction and he is put on trial.

And so, this clip is really self-explanatory and we've sort of hinted at it before, but it may be a good way to finally get at the man.

This human being, Muhammad Ali.

So could you roll the last clip?

- [Narrator] Two weeks later, an all-white Houston jury found Ali guilty of refusing the draft.

The judge, ignoring the more lenient recommendation of the prosecutor, sentenced him to the maximum; five years in prison and a $10,000 fine.

And he would have to surrender his passport.

Ali's lawyers immediately filed an appeal, prepared to go all the way to the Supreme Court, if necessary.

A process that could take years.

Ali remained free, but without his title or a license to box.

He fully expected that he would one day go to jail for his beliefs.

- We, who are followers of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad in the religion of Islam, we believe in obeying the laws of the land.

We are taught to obey the laws of the land as long as it don't conflict with our religious beliefs.

- [Reporter] Will you go into service as such?

- This would be a 1,000% against the teachings of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad, the religion of Islam, and the Holy Quran, the holy book that we believe in.

This would be all be denouncing and defying everything that I stand for.

- [Reporter] This would mean, of course, that you stand the chance of going to jail as a result of not going into service.

- Well, whatever the punishment, whatever the persecution is for standing up of my religious beliefs, even if it means facing machine gun fire that day, I will face it before denouncing Elijah Muhammad and the religion of Islam.

I'm ready to die.

- When I think about him saying, "If they want to put maybe for a firing squad tomorrow, "I'm ready to die before I abandon my religion."

That's it.

You can't teach that kind of thing in lectures and books.

That kind of thing has to be modeled.

And models turn into traditions, and traditions provide people with the mechanical memory to do the right thing.

That's what Muhammad Ali represented in that moment.

I mean, anybody now faced with a major decision in which the right way is clear and the wrong way is clear, but the consequences are dire, now they have a model that they can fall back on, psychologically, emotionally, spiritually; That's what Muhammad Ali represented in that moment and that, to me, that moment will live on forever.

- Wow.

I love that part of the film.

Howard, you've written so evocatively about the heritage, which is the title of one of your books, of black athletes and activism.

Can you explain today's athletes, whether they know it or not, what are some of the examples of how they're following that model that Ali set?

- Well, they are part of a lineage and I think that people...

I think we hear it.

I don't think we know it because you don't really know it until you're faced with it.

I think that one of the mistakes that I see, that I don't love, today is this idea that you are in the heritage of Muhammad Ali by owning a team, or by making money, or being part of an empire.

It's exactly the opposite of that.

He's exactly the opposite of all of these things that we have.

We have conflated athlete activism with commerce.

And so, to me, what I find in... What I find appealing to what's happening today is the citizenship element of the athletes.

When you see athletes doing things that allow them to speak for other people, I find that to be compelling.

I always remind myself when we go through this, whether we're talking about Colin Kaepernick or we're talking about LeBron James or whomever else, the level of risk is never going to be the same and it shouldn't be.

And that I feel like we compare people to Muhammad way too easily because it's incongruous to us to think about having a government come after you.

I think very few people have any idea of what that means.

And when I say the government coming after you, I'm talking about the citizens, not just the prison, being threatened with prison, but I'm thinking the number of conversations that people were having that were in absolute support of this man going to prison or worse.

And so, I'm very, very wary of ever comparing anybody to Muhammad.

- And the judge is given the chance, the prosecutor's had asked for a much more lenient sentence, he sentenced him to the maximum.

We cut to a newspaper, years after he's changed his name, they're still calling him Clay.

We don't know what he was up against.

I mean, that's one of the reasons why we wanted to make the film, is to describe that thing and I think, as I said before, Howard, I think you really hit the nail on the head, that this risk is a huge, huge part of the story, that sometimes we just don't put it together.

It's sitting there right in front of us.

This is a person who said he would risk a firing squad.

I mean, that's something.

- And it sounds hyperbolic but one of the things that I always remind people is if you really want to compare anybody to Muhammad, in terms of some of these risks, it has to be someone like Tommy Smith or John Carlos; they lost their careers.

And even someone like... And this is why I don't like the comparison game because it makes it seem like you're criticizing someone.

You're not, you're putting it into the proper context.

Is that at no point in his career has LeBron James ever been threatened with his live... And his livelihood has never been threatened by anything he's ever said in his career.

He's that protected, and that's a good thing, right?

You don't have to be destitute in order to be a good person or a good citizen, or do the right thing.

And the fact that they have that insulation is great, but that does separate you from Muhammad, which is also a great thing.

You don't want to be in that category.

He did this for us.

We don't need any others to keep doing this for us.

And so, I always feel when you come back to what he went through and you see it in the film, especially '67 to '70-'71, and even beyond, even by the time you get to '74, it's unprecedented what you saw because I honestly believe that most athletes, most people would have found some way to compromise and not go as far as he went.

He did not compromise at all and still found his way back.

Most players who do, most people who do what he did, they get broken, and he didn't get broken.

He was unbroken.

- He absolutely was.

And one of the comments that you made in the film, Howard, that I found really resonant was that the Rumble in The Jungle, him coming back and beating Foreman, he was made whole.

He was made whole, and then that, in terms of his story and what it meant, was so rewarding.

(speaking over each other) - I was going to say, Jesse, when we think about these stories, even Jackie, even Jackie Robinson, at some point, realized what had been taken from him.

Kurt Flood lost his career.

Colin Kaepernick lost his career.

Smith and Carlos lost their careers.

Everybody who talks, they find a way to break you.

And he had to win that fight, that's why Zaire is my favorite fight.

Zaire the resilient spirit of resistance.

It is everything.

And think about... Are we even watching this film if he loses that fight?

Is there a film if he lo...

It's a different film.

But the story.

Most of us lose when they come after you.

- Yeah, yeah.

So he was made whole, absolutely.

I agree with you.

And then, at the end of the film, we see him in pieces.

And the pieces of him that that made him so compelling, his voice, his movement, are what's robbed from him.

And the film even quotes Ali as saying, "This may be my punishment for the wrongs that I've done "and the way I treated these opponents "or the infidelities that I had "in my relationships and things like that."

So what part of the Ali story and the meaning of his story is filled by his condition at the end of his life?

And maybe, Rasheda, I'll start with you since you interacted with him personally and had to see him in this state.

How does that part of it fit into the overall message of his life?

- Well, I mentioned after I saw all the clips, the whole entire series, I mentioned to Ken, and Sarah Burns, that it was really beautiful to watch my dad, the good and the bad.

He was young, changing the world.

You're going to make mistakes.

But it's beautiful a man evolve into a better man.

He's always evolving into a better man.

He's not the same person he is now.

His convictions are the same but his choices aren't the same.

So it's beautiful to watch how my dad has come full circle, and kind of had regrets with the Malcolm X and Frazier and stuff.

He was human.

And when Parkinson's became a part of his life, my dad was devastated, and I think he disappeared from the media for a while because he was trying to figure out, wrap his brain around, what is this condition that is stopping me from being the person I was?

Because my dad's biggest asset was his mouth.

And so, then you get this condition that's muting him and now, he's barely some...

In some clips you'll see, he's barely whispering.

So that was his strength.

And so, my dad had to kind of really figure out, "What am I going to do with this "now new condition?"

But then, you see in 1996, where he's lighting the torch for the Olympics, he comes out of the dark and into the light and shows people, it's very brave move, that I could have Parkinson's, I can light this torch and I can still be great.

But he's not doing it for just himself, he's doing it for other people with neurocognitive diseases.

So that was the brave part, is that he's letting other people know that this does not define who you are.

This is what you have, this has not defined who you are.

You can still be great and have this condition.

So that was what was beautiful, to watch him evolving, even with this condition that, in some cases, would have broke most people down.

But we've got to remember my dad was always a fighter.

So throughout his entire life, he used his core principles, including his faith, to get through a lot of the trials and tribulations that he faced.

I don't think any other person had ever faced so many all in one lifetime.

So it's really wonderful to see that even with Parkinson's, he's still going out and doing what he loves best, and that's helping people.

And it's really inspiring and motivating, and it brought tears to my eyes, Ken, I have to tell you that, because when you're watching daddy struggling, walking and talking, and it's hard to do certain things in the late stages, he's still helping people and I think that's the overall message.

I think my dad wanted all of us, no matter what happens to you in your life, service to others is the rent you pay for your room in heaven.

- Yeah.

Howard, what do you think about this him being made whole in the Rumble in The Jungle, and then being broken down toward the end?

- Well, I always felt there was...

It's very poignant.

It's very painful.

And he's a professional, and this is what you know.

This is... We always talk about "the athlete's journey," and this is the athlete's journey.

And he was going to go until he couldn't go anymore.

There's always a piece of you that believes that if I just make this adjustment, I can win this fight or if I just do this, like... And boxing is the cruelest lesson because there's only one way to go out in boxing if you're not gonna... At some point, you're going to lose.

And for me, it wasn't...

The Zaire fight was the pinnacle.

The Larry Holmes fight and the Berbick fight, those are the ones where it was like...

Especially Berbick, it's like... You didn't want to see it.

It's hard.

It's almost like look at a family member 'cause you love Muhammad so much.

And I always felt like when you watched the end... 'Cause I remember, I was a kid.

I was in elementary and middle school when he was coming to the end.

You knew how much you love him 'cause you didn't want to see him fight, you didn't want him to go back out there.

And it's the fight, this is what it is when you're at that level.

There's only one way.

Very few people recognize, "I'm going to go without being told to leave."

Most athletes get told to leave.

- We're coming to the end, but we do have some audience questions.

And Ken, I'd like to throw this one at you from Brandon in Washington.

And he asked, "What was different from making this film "from making his favorite documentary, "Baseball"?"

And I'll sort of layer into that.

We love all of our children but we love all of them differently, so at this point in your career, what is special to you about this particular film compared to "Baseball" on all of your other children?

- You're muted, Ken.

- Sorry.

It's a good question.

I think that for us, the process is always the same.

It's really just a lot of discipline and hard work.

I mean, it's not akin to preparing for a fight, and then each fight is different.

Each one of these films is different.

And Howard has been around enough of our films to know that there's a kind of consistency to the discipline.

I mean, we put a name on it, "Muhammad Ali," and it comes out in September and that's it but we're working everyday on other films and even films that are over with have a life of their own.

I think what I said at the beginning is what is so special about this, is that we have necessarily dealt in the films, over the last 40 years, with extraordinary human beings.

I don't know anyone more extraordinary than him with all the flaws, with all the glory, and that I love this underlying message of love.

And in some ways, there's a kind of poetry to being silenced by Parkinson's for this big mouth of a guy.

Not to shut him up, as so many people wanted do, but to let him go in and make his spirit even brighter.

It's an amazing Testament.

And let us also say that we spend too much of our time relegating African-American history to February, our shortest and coldest month.

It's at the center of our identity and we don't want to deal with that.

We just don't want to deal with that, and that's all that you can do.

You cannot scratch the surface of American history without coming into contact with this essential contradiction.

And then, the extraordinary gift that African-Americans in the face of that hypocrisy and contradiction have nevertheless bestowed on us lessons, examples, models, as as Sherman would say, music, performance, excellence.

All of these gifts are not recorded equally.

There's nobody bigger than him.

- Thank you.

Thank you so much for that.

And thank you for bringing up the importance of black history in history overall.

And I'm glad that your film is premiering.

It's September 19th on PBS.

And here at The Undefeated, we believe in black history always, every month of the year.

So congratulations on this film.

It's a monumental achievement.

Thank you, Ken.

Thank you, Rasheda.

Thank you, Howard.

And to our audience, thank you for joining us.

Please tune in for more of these conversations and the film itself, which premieres on September 19th on PBS.

Support for PBS provided by:

Corporate funding for MUHAMMAD ALI was provided by Bank of America. Major funding was provided by David M. Rubenstein. Major funding was also provided by The Arthur Vining Davis Foundations,...