Critical Care: America vs the World

Special | 56m 5sVideo has Closed Captions

Critical Care: America vs the World

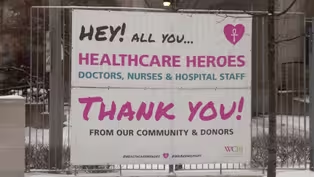

Millions of Americans have no health insurance, and live in fear that one illness could bankrupt them. Even though the U.S. spends far more on health care than other high-income nations, Americans still die of preventable diseases at greater rates. The PBS NewsHour special “Critical Care: America vs the World,” examines how other nations achieve universal care for less money, with better outcomes.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Major corporate funding for the PBS News Hour is provided by BDO, BNSF, Consumer Cellular, American Cruise Lines, and Raymond James. Funding for the PBS NewsHour Weekend is provided by...

Critical Care: America vs the World

Special | 56m 5sVideo has Closed Captions

Millions of Americans have no health insurance, and live in fear that one illness could bankrupt them. Even though the U.S. spends far more on health care than other high-income nations, Americans still die of preventable diseases at greater rates. The PBS NewsHour special “Critical Care: America vs the World,” examines how other nations achieve universal care for less money, with better outcomes.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch PBS News Hour

PBS News Hour is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipANNOUNCER: Funding for this program is provided by contributions to your PBS station from viewers like you.

Thank you.

DOCTOR: Let me feel underneath your arm.

BRANGHAM: It's a uniquely American problem.

The richest country in the world leaves tens of millions with no health insurance.

PARKER: It makes me feel that we don't matter.

TECHNICIAN: The thing about surgical theater... BRANGHAM: A country with such remarkable innovation.

NURSE: They don't know a discharge date.

BRANGHAM: And yet so many are struggling.

GLASS: Every one of us can name someone we saw suffer to death.

MARKS: You know, the deck's stacked against you.

PRESIDENT BIDEN: This is America's day.

BRANGHAM: As a new administration takes over, promising reform... We travel to four very similar nations, with four very different health systems, for clues.

JHA: I love how open and explicit they are about the fact that there are always choices.

WOMAN: Did you have a good sleep?

BRANGHAM: How do they care for virtually everyone, and do it for less money?

MURPHY: No one says, well, that's going to cost too much, so we're not going to do it.

PRESTON: Here it's a bit more humane.

It's like look, you know, there's a basic level of care that people deserve.

It costs, but you still deserve it.

BRANGHAM: And, amid a pandemic, does universal coverage help save lives?

MARTIN: If you require an ICU stay, if you need to be intubated and ventilated, all of those things are covered under the public system.

BRANGHAM: We have a problem.

What lessons can we learn from abroad?

"Critical Care: America Versus the World."

BRANGHAM: I'm William Brangham and our first stop is Houston, Texas.

There we met a little boy saved by American innovation.

A bouncing, rocking, joyful testament to the miracles of modern American medicine.

His life was transformed here, in what's called the largest medical city in the world: the Texas Medical Center, in Houston.

Here, doctors test artificial organs built from scratch... Technicians design robots to speed efficiency... Surgeons use virtual reality reconstruction to see tumors inside the body before ever making an incision.

And, kids like five year old Cason Cox come back from near-death.

Cason was born with only half his heart functioning normally... Those hints of blue in his skin a sign of a little body hungry for oxygen.

Most kids with this condition don't live very long.

SAVANNAH: I can remember it perfectly.

It was pouring rain outside, of course, and I was by myself, and one of my, my doctor told me that she sees that Cason's heart is underdeveloped.

It was a very few dark days for me.

BRANGHAM: But using new and highly complex surgical techniques, Dr. Jorge Salazar, that's him on the right, changed the course of Cason's life.

SALAZAR: Cason was going to die.

And had we done what we've always done, he would have had a transplant already, or, it's a hard thing to say, but he would have passed away already.

But now we have a normal child in front of us.

SAVANNAH: Doctor Salazar came out with the biggest smile on his face, and he said, "I did it, you did it, he did it, and it works."

So, I mean, I think we all started crying... BRANGHAM: Cason Cox is one story.

The Texas Medical Center performs over 180,000 surgeries every year.

It, along with other gold standard medical centers across the US, draw hundreds of thousands of patients from around the world.

The technologies and innovations created in the US Also get exported globally.

MARKS: You see what your options are around here... BRANGHAM: But just a few miles away, it's a world apart.

In north Houston, the mostly low-income residents here experience a very different health care story.

MARKS: I want you to see that within just a few miles, you have the very best, and the very worst, and it's just not fair, and it doesn't have to be that way.

BRANGHAM: Elena marks is the president and CEO of the Episcopal Health Foundation.

And last year, she took us on a tour.

Her foundation analyzed CDC data, documenting widespread disparities in this area.

NURSE: They don't know a discharge date right now BRANGHAM: She pointed out that the mostly black residents here are disproportionately uninsured... they often don't get good care until it's too late.

They die, on average, twenty years earlier than residents in other parts of Houston.

MARKS: You know, the deck's stacked against you.

If you could get to the Medical Center, that would be great, but you'd probably be really sick, because of the neighborhood you live in, by the time you get there.

BRANGHAM: We started filming this program last year, when China was dealing with an explosion of this mysterious new Corona virus.

But at that point, only a few, travel-related cases had been found in the US.

Still, many residents in this part of Houston, like Ruby Glass whom we met at her home with her mom knew that, if the virus landed here, these disparities would hit communities like hers the hardest.

GLASS: Can you imagine that if that were to hit and my community... a lot of us don't have insurance.

Where do we go?

BRANGHAM: Just a show of hands, has anyone around the table ever worried about whether you could pay a medical bill?

(laughter).

BRANGHAM: Glass gathered a group of people from her community to talk with us and we heard about the very disparities that the pandemic would exacerbate.

Many in the black community in Houston felt the healthcare system wasn't on their side.

BONNER: You know, from the poorest of the poor to the richest of the rich, we don't get the same quality of care.

WEATHERSBY: It's kind of the implicit bias of the medical field.

BRANGHAM: Towards people who have Black skin?

WEATHERSBY: Yes.

It's true.

GLASS: Every one of us can name some people we saw suffer to death.

NASH: It's all greed.

Pharmaceuticals, insurance companies.

It's greed.

GLASS: The pain sometimes is not pain from a nerve, it's pain from a broken heart, from knowing that nobody really cares that you're suffering.

BRANGHAM: Pandemic aside, the US Spends about $3.8 trillion on health care every year, it's nearly a fifth of our economy.

As a percentage of GDP, that's roughly twice what most high-income nations spend.

Our total health care spending is more than all these nations spend combined.

And yet Americans still die of preventable and treatable diseases at higher rates than in other high-income countries.

Ours has been called "The most expensive, least effective" health care system in the modern world."

Lack of health insurance, or the high cost of health care, is a huge barrier for millions.

In a poll last year, more than one in three people said they skipped medical treatment because of money... That includes people with health insurance.

According to the most recent data: more than 30 million Americans, about 12% of people under 65, have no health insurance at all.

During the pandemic, experts estimate millions more joined their ranks.

For many years, Houston resident Lakeisha Parker was among the uninsured.

She was a certified nursing assistant.

PARKER: I was proud of that work, I enjoyed doing it, because I love to be able to help people.

So, what I would do is go into people's homes, after their surgeries or illnesses, and assist them with getting back to life, daily activities of living, bathing, fixing them a small meal.

BRANGHAM: That's very intimate work with people, right?

PARKER: It is, very intimate work.

BRANGHAM: But Parker says the pay wasn't great, she says the most she ever earned was about $13 an hour.

And it never came with health insurance she could afford.

PARKER: I'm actually working in healthcare, and can't afford to pay it.

That's not right.

How, you know, can you come to this, go and be a help to other people, and then when you need the help it's not available for you, or if it is available, it's hard to come by.

So no, that isn't fair.

BRANGHAM: Even before the pandemic, Texas had the highest uninsured rate in the nation.

Roughly 18% of Texans, that's over 5 million people, didn't have insurance.

DOCTOR: How's that working out for you?

BRANGHAM: And the state didn't expand Medicaid, which would insure more low-income Texans, under the Affordable Care Act.

So, like many, Parker went for years without checkups, or seeing a regular doctor.

Too expensive she said...

But then, lying in bed one night, she discovered a lump the size of a tangerine in her breast.

It was malignant cancer.

NURSE: All right, relax your arm for me... BRANGHAM: Parker found this Houston clinic that would treat her on a sliding scale, based on her income.

Only after the cancer diagnosis did she qualify for a special Medicaid program.

So the tumor, along with 33 lymph nodes, were removed.

While surgery was a success, it, along with the chemotherapy and radiation, left her with limited use of one of her arms.

DOCTOR: Ok, not bad.

Let me feel underneath your arm.

BRANGHAM: Do you think if you had had health insurance, you would have found this sooner?

You would've been going to the doctor sooner?

PARKER: If I would have had insurance for me, at that time, healthcare that I would have been able to afford, I would have easily accepted it.

But again, it comes the question of having somewhere to live, having something to eat, gas to get back and forth to work.

So, you know... BRANGHAM: Those were the choices you were wrestling with?

PARKER: Of course.

You know, those are everyday life choices that a lot of people have to make, based on their income.

BRANGHAM: The weakness in her arm cost her her job.

With no money, she lost her apartment.

At the time of our interview, Parker was homeless, unemployed and living in a shelter.

JHA: Houston represents both what is the best of American healthcare, and really what is the worst of American healthcare.

You have parts of Harris County, which is where Houston is, where life expectancy is lower than what you see in many third world countries.

BRANGHAM: Dr. Ashish Jha, the dean of Brown University's School of Public Health, traveled with us for this program.

JHA: I reject that dichotomy that, somehow, we have to have 20, 25% of people uninsured if we're going to have a really highly innovative healthcare system.

There are many reasons to reject that.

So, take a state like Massachusetts, where I live.

It's also very dynamic, incredible new innovations happening.

And yet, pretty much everybody in Massachusetts is covered.

Look, innovation, there is a cost to it, it does raise the spending of healthcare.

That is a reality.

But we can afford to pay for that innovation, and still make sure everybody is covered.

BRANGHAM: So this is the challenge for health care reform going forward... How to preserve the high-quality care that saves the life of a boy like Cason Cox...

While helping the tens of millions, like Lakeisha Parker, who have no health insurance at all.

BRANGHAM: Many nations around the world have already struck that balance and done so successfully...

But before we learn about those places, we traveled to Princeton, New Jersey to talk with two of the world's top health policy experts.

They'll be our occasional guides throughout this program.

One we've already met, Dr. Ashish Jha of Brown University.

The second is Tsung-Mei Cheng.

She's a Health Policy Analyst at Princeton University.

She and her husband, the late, renowned health economist Uwe Rheinhardt, have advised world leaders, and helped design Taiwan's universal care system.

So Ashish, why is it that we have those kinds of disparities here in the US?

JHA: You know, William, we've made a bunch of political choices.

We have more than enough capacity, certainly more than enough resources to cover everybody.

But we have chosen not to do that, again from a policy point of view.

This is not a tradeoff that we have to live with.

We can continue to have the best health care and cover everybody.

We just, for political reasons, we've chosen not to do that.

BRANGHAM: May, do you see it the same way, that this is a decision we have made, that we are going to be okay with a society that looks like this?

CHENG: Yes.

In this country, we're very different from these other countries that have health insurance that covers everyone.

Health reformers in Europe, in Asia, they would make explicit that social ethic that underlie that health system.

BRANGHAM: We're going to establish a goal and then get there.

MAY: Right, to say yeah, what is it that we value as a society.

And so then they build their health care system around that.

But in this country, because we have never been able to achieve a social and political majority consensus, we live with the status quo, which is people who have insurance get care and those who don't don't... And the ones without health insurance, we know they get sicker, and many of them die.

JHA: Yeah, so the disparities we see in the U.S. has certainly driven a lot of people to look to other countries and to look to single-payer systems, which have a bunch of advantages, right.

They cover everybody, they are administratively simpler, and they have a lot more equity potentially built in.

WOODRUFF: You have especially ambitious plans... BRANGHAM: In the last election cycle, the Democrats had a vigorous debate about whether to push for a single payer, Medicare-for-all plan, its champion was Senator Bernie Sanders.

SANDERS: We are the only major country on Earth not to guarantee health care for all people, which is why we need Medicare for all.

BRANGHAM: To look at one of the inspirations for Medicare-for-all, we visited one of the world's preeminent single-payer systems, in the United Kingdom.

ANGELINA: "Good morning to you!

Did you have a good sleep?"

BRANGHAM: Even with the help of his mom, Liam Murphy still struggles to wake up each day.

ANGELINA: I thought you would be dreaming about Charlotte.

Right?

Why Charlotte?

(Liam makes sound).

BRANGHAM: Liam has down syndrome, epilepsy and chronic lung disease... he's dealt with these since the day he was born.

The ten year old lives in Watford, England with his parents, Gary and Angelina and big sister, Laura.

They have to be constantly vigilant for trouble.

ANGELINA: Don't start, don't start.

GARY: You're ok Liam.

ANGELINA: Can you get the mask please?

BRANGHAM: Like this seizure... MURPHY: No, I can't have that.

Not in the nasal cannula!

Turn it down.

GARY: You're all right.

Come on out of that.

BRANGHAM: Dozens of times a year, episodes like this will send Liam to the hospital.

He is always at risk of dying.

ANGELINA: Good boy.

BRANGHAM: Liam's life, and the incredible care he gets, are a testament to the United Kingdom's national health service... known as the NHS.

Residents of the UK pay taxes to the government that support the NHS.

The government is then the single payer for health care It pays doctors and hospitals and covers nearly all costs.

CAREGIVER: Seatbelts on.

BRANGHAM: For Liam, that's all his medicines and hospitalizations...

It pays for caregivers that come several times a week... the NHS even paid for this chair and standing frame to help him exercise.

CAREGIVER: So he's been up for about half an hour now, hasn't he?

So that's really good, Liam!

GARY: No one says, well, that's going to cost too much, so we're not going to do it.

BRANGHAM: You've never heard those words?

GARY: No.

If we call an ambulance, an ambulance will be here in five minutes to pick Liam up, and take him to hospital.

A specialist team will come out, pick him up, put him on their ventilators, take him to intensive care, and an intensive care bed will cost 2000 pounds.

No one mentions the money, they just do what you need to do.

Without the NHS, we would be bankrupt, and Liam would probably be not with us.

REPORTER: July 5th, the new health care service starts... BRANGHAM: The national health service was built from the wreckage of World War II... something of a gift from the government to a battered and impoverished nation, which welcomed it.

And today, it's still considered the UK's great equalizer.

EVERINGTON: Ok, Dolores, do grab a seat.

BRANGHAM: Everyone, regardless of profession or income, has access to that system... from primary care to, as needed, the full range of specialty services.

EVERINGTON: Try and let me just take the weight.

BRANGHAM: Patients' point of entry to the system is through their general practitioner, doctors like Sam Everington.

EVERINGTON: There's no cost attached to going to see a doctor in this country, at all.

And that's really powerful.

BRANGHAM: Do you ever think about how much things are going to cost when you come to the doctor?

CLEMENT: Nope, it doesn't cross my mind, but the thing is, because I'm diabetic, in England if you're diabetic, your prescriptions are free, so I don't have to pay for it anyway, so it doesn't cross my mind.

BRANGHAM: Despite those benefits, per person, the NHS spends less than half what we spend in the US.

Including a lot less than we do on administrative costs.

And the NHS generally gets better health outcomes than we do.

Life expectancy is longer here than in the US.

In part, because people in the UK Suffer much lower rates of chronic diseases like diabetes and hypertension.

It's hard to overstate just how beloved the national health service is here in the UK.

Some people have referred to it as the closest thing this country has to a national religion.

In fact, in 2018, when the service had its 70th anniversary, they had a huge celebration here at Westminster Abbey.

We were in the UK in the early days of the Corona virus' spread.

The WHO Had declared it a public health emergency...

The US had only a handful of confirmed cases at the time.

Cases would soon surge in the UK, and when they did, a big part of the government's stay-at-home appeal was "protect the NHS."

JOHNSON: Families everyday are continuing to lose loved ones before their time.

BRANGHAM: But even so, when we were there, we heard of growing disillusion with the system.

In the rural town of Dorchester, England, we met 77 year old Olive Parfitt.

PARFITT: I was supposed to have the operation in August.

And 14 hours before the operation, they canceled it.

BRANGHAM: Parfitt needed to have her knee replaced, but she'd been on a waiting list for nearly a year.

She said she took 4 painkillers just to take this short walk around her housing complex.

PARFITT: Because I've walked so badly for over a year, I'm starting to throw the other knee out.

BRANGHAM: Oh really, because you're compensating?

PARFITT: Yeah, so you wobble.

If I have a heart attack tomorrow, it's the best thing, they will take me in, they will do it.

But when you've got what I call disabilities that are not life threatening, they can't cope.

BRANGHAM: Parfitt has been a strong supporter of the NHS her whole life.

But now, after a lifetime of paying in, she feels left out.

PARFITT: I started working at 15.

I didn't have time off to have children.

I've paid for schools I haven't used; I've done it willingly.

But then suddenly, when you get to a certain age, and you want to get it back out again, it's not there anymore.

BRANGHAM: An estimated 10% of UK citizens pay out of pocket for supplemental private insurance, in part, to avoid long waits.

Problems like these also cause tens of thousands of residents to seek some care abroad.

PARFITT: You just think nobody cares about me anymore.

I'm an old girl, probably if you carry on long enough, she'll pop her clocks, and then we won't have to worry with her.

PROTESTOR: Whose NHS?

Our NHS!

BRANGHAM: Funding for the NHS has been a constant problem, and a political flash point.

Different administrations fund the NHS at different levels, and the UK's recent austerity measures have delayed upgrades, and made serious staffing shortages worse.

DILLON: There are always choices, and inevitably and in every healthcare system, there are always limitations on what the system can do.

BRANGHAM: Sir Andrew Dillon was, until last Spring, the long-time head of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, known as "NICE."

It's a sweet acronym, but in the US its work has been likened to a "death panel" NICE is one of the NHS' crucial cost control mechanisms, it examines the evidence for any given treatment or procedure, and weighs which ones give the most cost-effective benefit for patients.

DILLON: Making sure that we really understand the benefits of one option over another, making sure we really understand the value for our money, particularly in a publicly funded system that has to account for how money is used, is really important.

JHA: I love how open and explicit they are about the fact that there are always choices.

It's not like in the US we're not making choices.

We have rationing in the US.

It's primarily based on your ability to pay and whether you have health insurance or not.

So the National Health Service tries to make explicit the rationing choices it's making.

CAREGIVER: You're very cheeky!

BRANGHAM: Since we first filmed with them last year, Liam was hospitalized and in critical condition.

This time, right in the middle of the UK's first wave of the pandemic.

But he's back home now, and doing ok. ANGELINA: The general ethos that I've experienced is that nobody has given up.

And every time we have an episode where it could go either way, we come together and say, 'He hasn't given up, therefore we aren't giving up', and then the health professionals go, 'Good enough for me,' and they keep going with his care, as well.

LAURA: Look who's come to see you?

BRANGHAM: The Murphy's say the NHS isn't perfect... CAREGIVER: Is that your rabbit, Liam?

BRANGHAM: But it's given them more precious time with their son.

BRANGHAM: May, when you look at the U.K., it is a very appealing system.

We see that there are problems with it, but there is this system in the United States, Medicare, that is similar, that is very appealing, that people adore.

Why do you think that hasn't gotten more traction here than it has?

CHENG: A couple of reasons I'll mention.

One is that you're pitting private health insurance with single-payer, government-run health insurance, and you know it's human nature that we're afraid of the unknown.

That's one important point.

And the other point is that I think that a single-payer system cannot work well in this country because see, in single-payer systems, government sets prices.

And that is their main cost-containment tool, price setting.

In America, hospitals, doctors, pharmaceutical companies, they are very, very strong and powerful.

You are basically controlling their revenue and profit.

So here you have the political reality of a very powerful supply-side against a Congress which basically accepts their political contributions.

BRANGHAM: Ashish, is that your sense as well, that Medicare for All or a single-payer system in the U.S. is really politically unfeasible because of those interests?

JHA: So, when I look at the single-payer system of the U.K., you have to remember the context in which it was created.

Wherever you are in the political spectrum, no one runs and wins in the U.K. saying, "I'm going to take apart the NHS."

That political economy is very different here.

Here you have a Congress, a House that's up for election every two years.

In almost every congressional district, the single biggest employer is the hospitals.

You can't do price control very effectively in that context when everybody in Congress's incentives are, "Get lots of money to hospitals and doctors."

So I think the political setup in the United States is certainly much, much harder.

Impossible?

I don't know.

I mean politically lots of things may be possible.

But the setup is very different, the narrative is very different.

OBAMA: "Today, after almost a century of trying..." BRANGHAM: That's why president Obama, in crafting the "Affordable Care Act" a decade ago worked with the existing system, while trying to expand coverage for millions more.

DOCTOR: Excellent, your lungs sound clear, no wheezing.

BRANGHAM: And part of the inspiration for that law came from the next nation we visited, one that's achieved universal coverage: Switzerland.

(overlapping chatter).

The Swiss shop for health insurance a lot like their groceries...

There's a wide array of choices.

SABINE: You want a cheese?

Which one?

BRANGHAM: This cheese, or that one?

GIRL: What about the parmesan?

BRANGHAM: One with the high deductible?

Or one with the high premium?

For all Swiss families, like the Preston's, it's a system that, in some ways, is even more market-driven than our own.

But the big difference?

Everyone here is covered.

The idea behind it is similar to what we heard in the UK, a spirit of "social solidarity", and it's what impressed American-born Jason who's a teacher when he moved here and married Sabine, who is Swiss.

PRESTON: For me it's just sort of a basic right, and they seem to appreciate that.

BRANGHAM: Do you see it that way, too?

I know that the Swiss talk about it that way, but you buy that idea that health care is a right?

PRESTON: Yes, because, I mean yeah, again, coming from where I come from, there's this sort of negativity in the States that, you know, if you're poor then it's almost like you deserve to die, right, for being poor.

That's kind of the feeling, the vibe that's given off.

That if you can't afford it, well you don't deserve to be well.

BRANGHAM: Health insurance in Switzerland is costly, Jason and Sabine pay about 16% of their income on premiums, which is more than the average US family.

On top of that, the average Swiss pays more out of pocket for things like co-pays than the average American.

But the Preston's like the care they get, and...

They like buying into a system that protects everyone.

PRESTON: Here it's a bit more humane.

It's like look, you know, there's a basic level of care that people deserve.

It costs, but you still deserve it.

And I think that the Swiss government's commitment to that is spot on.

BRANGHAM: We were in Switzerland in late February last year, Corona virus cases were exploding right across the border in northern Italy, prompting big shutdowns.

But Switzerland, at that point, was still operating normally.

We traveled to the city of Bern, to meet one of the men who helped design Switzerland's health care system.

Thomas Zeltner was the top health official here for many years, and is now chairman of the World Health Organization Foundation.

ZELTNER: In the 90s, there was a debate on "Is health care such an essential part of well being, and feeling safe in your country, and in your neighborhood, that you want that everyone has access to it?"

And actually it was something like 70% of the population who said 'We want that.'

BRANGHAM: Wow.

That is a resounding yes.

ZELTNER: Yep.

BRANGHAM: Zeltner says one of the crucial innovations was separating health insurance from employment... which allowed the Swiss people to keep their health insurance during the pandemic while millions of Americans lost theirs when they lost their jobs.

They've been able to separate the two, but instead of making the government the single payer, like in the UK, they've made it so that a wide array of insurance companies can flourish.

ZELTNER: And the fun thing is you can choose, and I just told a friend, you know, I can choose to go to the barber here, or there.

Since 30 years, I go to the same barber.

BRANGHAM: And he does a nice job!

ZELTNER: But the option to be able to choose is, you know, a kind of a freedom.

BRANGHAM: This is all now baked into society... as Swiss as this country's famously punctual rail system.

There are roughly 60 private insurance companies selling plans.

But the Swiss government does take a firm hand in regulation: it mandates basic coverage all plans must include, and the government sets the prices that can be charged for medications and procedures.

We met up with New York University's Victor Rodwin, he's a health policy expert who was traveling across Switzerland studying its health care system.

RODWIN: In terms of trust of the medical profession, and satisfaction with the system, Switzerland comes out extremely high.

You ask the Swiss about the quality, they are happy that they have the choice to go to any hospital, go to see any doctor.

They're not restricted by tough networks.

BRANGHAM: The Swiss live about five years longer, on average, than we do, and they're a lot healthier than we are.

Suffering far lower rates of chronic diseases like diabetes, and hypertension.

RODWIN: There's a sense of quality in this country which goes from chocolate to cheese, to watches.

(laughter).

And in health care, it's the same as...

They do things carefully and at generally high quality.

Swiss officials say there's another main reason they achieve these results: it requires everyone, like waitress Mel Hirsig, to have insurance, no excuses.

It's similar to the individual mandate that was built into the Affordable Care Act, but unlike the ACA's, this mandate has sharp teeth.

The government will dip into your paycheck if you don't buy insurance.

that's partly how the Swiss get to universal coverage, but for young people like Hirsig, who don't need a lot of medical care, it can seem like a big imposition.

BRANGHAM: If the government wasn't forcing you to buy health insurance, do you think you would buy it anyway?

HIRSIG: No, I wouldn't have it, full.

BRANGHAM: Just because that monthly cost is too much?

HIRSIG: And because I don't use it.

I don't get my money's worth out of it.

BRANGHAM: The government offers premium subsidies for lower income workers and it caps yearly out-of-pocket expenses, so, unlike the US, people rarely go bankrupt from medical bills.

WOMAN: That's the list of all your debt.

BRANGHAM: But those premiums can sometimes lead to serious debt for middle-income families.

This woman didn't want her name revealed because of the stigma around debt.

Her husband had multiple surgeries, lost his job and their income dried up.

WOMAN: We were getting subsidies to help pay for the health insurance, but at the time it was unaffordable for us.

I think it is expensive, but I think the healthcare is also very good.

BRANGHAM: So even though the costs put you at real financial peril, you still see some benefit to the system?

WOMAN: Yes.

I see that if everybody pays into health insurance it makes the quality of health insurance better for the population.

BRANGHAM: She's talking about how Switzerland looks out for those who are often left out in the US.

UNISANTÉ: We see all sorts of patients.

The poor, political asylum seekers, undocumented people, and increasingly, those experiencing homelessness (speaking in French).

BRANGHAM: Dr. Patrick Bodenmann practices at Unisante Medical Center in Lausanne.

The day we visited, he was caring for Kamelou Issaka.

He came here recently from Togo to apply for political asylum, and finally got care for a years-old leg injury.

Isaaka's mom back home cried when he told her.

ISSAKA: I said, "Mother, don't weep, because in Switzerland they are very kind.

They help me, they protect me, they care for me."

And I say it is good.

BRANGHAM: The US of course is much bigger than Switzerland.

New Jersey has more residents than this country.

Switzerland also has a much lower poverty rate.

But Ashish Jha points out there's a big cultural difference as well.

JHA: And that is kind of the rule-following mentality of the Swiss.

That the government says, "You must buy health insurance," and everybody says "Yes, ok we will buy health insurance."

And so, as opposed to in America, where we bristle when the government tells us we have to do anything.

And we bring up the broccoli argument: what if the government made you eat broccoli.

The Swiss don't worry about eating broccoli.

They think "If the government thinks that's something we ought to do, we'll do it."

For the record, the Preston girls, not big fans of broccoli, but Sabine and Jason are fine with it.

They also know the insurance mandate costs them a lot, but they see it as part of the greater good.

Part of being Swiss.

BRANGHAM: I think I know why the Swiss are so healthy, it's cause they breathe that mountain air and get those use of the Alps all the time; that's why their system works, it has nothing to do with their insurance system, right?

JHA: If we all could look at the Alps all day, we'd all be better for it.

BRANGHAM: Right.

As we're showing in that system, Ashish, it is a private insurance system, but the government really has a firm hand in all this, and that seems crucial to their success.

JHA : Absolutely.

So it is a very private system, in many ways is far more private than our system.

They don't have a large public payer and yet, there's some very specific rules of the road, and you really can't mess with them.

It's a pretty heavily regulated, highly privatized, highly capitalistic system.

It feels like a contradiction to a lot of people, but it works.

BRANGHAM: May, what is your sense of, the individual mandate in Switzerland seems to be so central to what they do, and yet we saw what happened here, where the individual mandate in the Affordable Care Act was something that became an incredible lightning rod and doomed the efforts, in some ways, of parts of the Affordable Care Act.

CHENG: That's right.

It is a central part, because for a universal health insurance system to work, you need to have the broadest base from which you can collect premiums, you need to have this stool that's held up by three legs.

First leg is a mandate, ok. Second leg is guaranteed issue.

That you can't turn people away.

The insurance companies must accept everybody that comes to them for insurance.

And the third one, which is really important, is that you must have adequate government subsidies to people who need help to pay for their health insurance premiums.

BRANGHAM: So we have seen these two different systems, a single payer, and a largely private system, but there are hybrid systems that also might be a model for the US.

JHA: Yeah, absolutely.

So, there are a series of countries that have a combination of both public and private.

Singapore, France, certainly Australia.

Places that have managed to have both a significant public system, and a significant private system next to each other.

BRANGHAM: So we traveled 10,000 miles to Australia.

CAROLE: Hello!

FEALOFANI: How are you?

Nice to see you!

BRANGHAM: Don't be fooled by this happy scene.

This is a family divided.

PAUL: You look lovely!

BRANGHAM: Ok, it's not quite that serious...

But the division is stark when it comes to, of all things, health insurance.

FEALOFANI: Really?

BRANGHAM: On one side: Fealofani Elisara and her husband Paul Dunn rely on Australia's public health care system.

It's known as Medicare, it's paid for by taxes, and it's available to all Australians and permanent residents.

FEALOFANI: We talk about that all the time.

BRANGHAM: That public system has gotten them through some pretty traumatic stuff: IVF treatment and a hysterectomy for Fealofani, and for Paul...

Brain surgery to remove a malignant tumor.

At first they panicked over what they feared would be a huge price tag.

DUNN: I was really scared.

I was like, "What am I going to do?

Do I need to start a GoFundMe?"

Which my friends did for me and my family did for anyway.

BRANGHAM: But then you found out that the public system was going to cover a majority of that.

DUNN: Majority of that, yeah.

ELISARA: It covered all of it.

DUNN: It covered all of it, actually.

BRANGHAM: On the other side: Paul's parents, Carole and Ross, are evangelists of the private sort... CAROL: Ancillary is good too.

You get $2000 worth of dental.

BRANGHAM: They skip over the public system and buy their own private insurance coverage.

About half the country does this.

Carole had her knee replaced a few years ago and said she got great care and terrific perks.

She says if she'd been in the public system she'd be in agony, on a waiting list.

This hybrid system, with the public Medicare system as a base, but then layered with private insurance on top, is by design.

They're meant to work together, with the private system taking pressure off the busier public one.

This unique set-up meets two basic values, says health economist, Rosalie Viney.

VINEY: Just as one of the tenets of Australian's beliefs, is that they should have access to public care, there's also an element that choice is part of what a lot of Australians seem to value.

BRANGHAM: Why would I, as an Australian, ever want to pay extra if I can get it for free?

VINEY: So, some of it is about access to elective care at the time when they want it.

Some of it is about access to the amenities that a private hospital might offer.

BRANGHAM: Amenities like...?

VINEY: Private room, better food, those sorts of things, a choice of menu.

Some of it is about choice of your own doctors.

But some of it is actually about getting quicker access.

KOZICKI: The whole sense of waiting for me, like, with endometriosis you could be in bed, like, chronic pain.

So, that could mean a year without working... Two years without working.

And that's not feasible either.

BRANGHAM: A private health plan makes sense for Sarah Kozicki.

She's training to become a nurse, and every couple of years, she needs a costly surgery for endometriosis, which is a painful disorder involving the uterus.

KOZICKI: So, for that, I choose to have private health insurance that I can go and have surgery when I need to have surgery.

I can do it in a private hospital, or do it in a public hospital as a private patient, and I get to choose my specialist.

BRANGHAM: We were in Australia in mid-March of last year, right as the WHO declared that COVID-19 was officially a "global pandemic."

There were only about 200 official cases in the country at that point, but infections were growing every day...

Even before the pandemic, the health outcomes for both of Australia's systems, the public and the private, had been quite good.

Australians live longer than Americans, they're healthier, and they see their doctors more.

They don't die of preventable diseases nearly as often as we do.

And they get these results for less money... spending about half what we do, per person.

Costs are kept low partially because the government sets prices for drugs, treatments and other expenses.

But there's one major problem.

Pre-pandemic, increasing numbers of Australians were choosing not to buy private insurance.

People like Emily Maguire.

She's a teacher, she's healthy, and she says the rising cost of living makes it hard to justify paying for a private plan.

MAGUIRE: And like, the public health system is so great.

Like, they do a great job.

So, I'm just like no, I think I'll trust them, and if I need something then I'll pay for it myself.

I'm not too worried.

BRANGHAM: In recent years, tens of thousands of Australians have been dropping their health insurance and this is causing huge strain for the insurance system.

Younger people who tend to be healthier, and don't use as much insurance have been leaving the private market, while older people who tend to be sicker, and use their insurance more have been staying in.

This cycle drives up costs, and the problem gets worse.

Remember, the private system is meant to relieve pressure on the public one.

So now, the government is spending around $5 billion a year in subsidies to encourage people to buy private care.

And that cost keeps going up.

MOHAMED: What would be better is if we actually took a reinvestment of those private health care dollars, and put it into our primary health care system.

Why haven't we got this right?

BRANGHAM: Janine Mohamed has a very different idea where those billions ought to go.

She runs the Lowitja Institute, a research organization that advocates for better health care for Australia's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations... MOHAMED: Howya been?

WOMAN: Good!

BRANGHAM: People who've suffered decades of racism and discrimination.

MOHAMED: Not bad.

So now we'll check your blood glucose levels.

BRANGHAM: On average, people from indigenous groups, like Kylie Battese... suffer higher rates of chronic diseases than their peers.

Mohammed says they die 11 years earlier on average than non-indigenous Australians, but funding for their care has been inadequate.

MOHAMED: It just seems ridiculous that those funds can't be redirected to Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander health when we know that we have the poorest health outcomes in Australia.

So, for us, it's, you know, giving the most privileged more funding.

KYLIE: I've been here for six years.

BRANGHAM: Oh that's great.

This debate shows that even after a country achieves universal care, there's always more work to do... improvements to make for future generations.

Aww, thanks Pappa D!

But the members of the Dunn family have given up trying to convince each other that their health care choices are best... CAROLE: "Cheers, guys."

FEALOFANI: "Cheers!"

BRANGHAM: They're okay with the division.

CAROLE: And I was going to say, 'Vive la difference.

GROUP: Vive la difference!

BRANGHAM: I want to shift gears here for a second, to talk about, obviously, the elephant in the room, the reason why we are sitting so far apart, and we have the windows open, and that's this pandemic that we are all living through.

As we've been reporting this, the question keeps coming up: does having a universal care system in your nation make it easier, does it give you extra tools, to fight a pandemic when one arrives.

Ashish, what does the evidence tell us in that regard?

JHA: The evidence in my mind, is having a universal system doesn't automatically mean you will be able to manage a pandemic well.

We can look at a place like the UK, which has not done a great job managing the pandemic.

Lots of infections, lots of deaths.

But not having a universal system certainly hampers it.

It's sort of a necessary but not sufficient tool.

CHENG: I'll give you a very concrete example.

Taiwan, which has this high performing single payer system, 99.9% of the people are insured.

To date, they have lost nine people from Covid.

BRANGHAM: Nine.

CHENG: Nine.

And total number of cases is under 1,000.

985, something like that.

But then the low case numbers, that has to do with other aspects of how Taiwan's government managed the healthcare crisis.

BRANGHAM: To see how another universal care system responded to the pandemic, we recently went up to check in on our northern neighbor.

CASTELLANOS: I would say about the seventh day I woke up with this massive headache, just pain in my skull, my neck, my spine.

I never felt anything like it before.

BRANGHAM: Ruth Castellanos started feeling sick from the Corona virus last May.

Her symptoms kept progressing.

And then one night, at home in Flamborough, Canada, it got worse.

CASTELLANOS: I woke up and I couldn't breathe.

My husband was sleeping.

My dog was sleeping.

I was trying to wake them, but I didn't seem to have strength in my arms.

And I thought, I'm going to go.

This is my time.

And I just looked to my husband one more time.

And then I just said okay, I need to just be brave because this is going to happen.

REPORTER: 155,000 doses of Pfizer arrived... BRANGHAM: The immediate crisis passed, but her other symptoms didn't.

They were so constant, she had to quit her two jobs.

Castellanos struggled at first to find a doctor who'd listen, and not blame her symptoms on anxiety.

CASTELLANOS: I tried to get some food and it was so much work, I couldn't even get it out of the car.

BRANGHAM: She captured her anguish in this video.

CASTELLANOS: I'm in so much pain... BRANGHAM: She's now a Covid "long-hauler," takes twenty different pills a day, and sees a neurologist, a cardiologist and a pulmonologist.

CASTELLANOS: I have an appointment next Thursday... BRANGHAM: While she has to live with this chronic condition... because she lives in Canada with its taxpayer funded, universal health care system, at least she doesn't have to worry about getting good care... or affording it.

CASTELLANOS: That's all part of our universal health care.

So I'm not paying any of those bills.

BRANGHAM: But does a universal system help more broadly when a pandemic breaks out?

MARTIN: Welcome back.

BRANGHAM: Dr. Danielle Martin is a family doctor and Executive Vice President at Women's College Hospital in Toronto.

MARTIN: The first and most obvious success of the Canadian health care systems in response to the COVID-19 pandemic is, that if, anyone has symptoms of COVID-19, they've been able to access testing free of charge and, heaven forbid, if you require an ICU stay, if you need to be intubated and ventilated, all of those things are covered under the public system.

BRANGHAM: Martin notes that Canada has lost many thousands of people to Covid, and has struggled, in parts, with its response.

MARTIN: And this is one of the things about COVID-19 is, it's exposed in every country the places where you built something strong from the foundations up, and it's also exposed the places where you're running around trying to patch things on in order to make it work BRANGHAM: Canada is a single-payer system, though, here, each of the 13 provinces and territories control their own system.

Doctor and hospital care is covered, but major gaps exist.

One example: most medications outside the hospital aren't covered, but supplemental insurance, which most get through their work, picks up the slack.

During the pandemic, Canada has had much better outcomes than the US.

Its overall death rate is about three times lower than America's.

MOORE: So we have built quite an effective system within Ontario to respond to COVID-19.

BRANGHAM: Dr. Kieran Moore is the head of public health for Kingston, and the surrounding region, in southern Ontario.

This holiday destination could've easily become a Covid hotspot.

But, this area of roughly 200,000 people has had only one death during the whole pandemic.

MOORE: That's the benefit of having a universal health care system, because all partners are working together.

There's not a private/public separation of responsibility.

NURSE: That's in her period of acquisition and you said that was a week and a half ago.

BRANGHAM: Once a positive case is identified, nurses spring into action.

NURSE: Our records indicate you were exposed on February 14... BRANGHAM: With daily calls, they make sure people are safe, staying home and not spreading the virus.

NURSE: All right, so you haven't traveled outside of the province in the last 14 days?

BRANGHAM: Public health departments can levy serious penalties if you don't.

NURSE: You can be subject to a fine of $5000 per day.

BRANGHAM: Canada's system has also largely avoided what we saw in certain parts of America: hospitals being overrun, and straining to care for a surge of Covid patients.

WUNSCH: We haven't experienced anything like colleagues in places like New York City have experienced or elsewhere in the world where they were hit the hardest.

BRANGHAM: Dr. Hannah Wunsch works in critical care medicine at Sunnybrook Health Sciences in Toronto.

Because hospitals here operate within a coordinated system.. SCOTT: It's been really busy up here.

BRANGHAM: An oversight board, like this one, can shift patients from stressed facilities to those with extra capacity.

SCOTT: We have over 50 patients in the hospital, 15 in the unit, 14 ventilated... BRANGHAM: That often didn't happen in places like New York during the early days of the pandemic.

WUNSCH: Baseline, US hospitals and health networks are very much competing against each other.

And so while many of them have learned to function together over time out of necessity, it's not baked into the system, it's not inherent to the way they function in normal times.

BRANGHAM: But Canada's experience also shows the gaps that can occur when a country achieves universal care.

But stops there.

Canada has seen many of the same problems we've seen in the US, with our fragmented system.

The vast majority of Canada's COVID-19 deaths, roughly 70%, have occurred in long-term care facilities, most of which aren't a part of the public system.

The toll has also been particularly hard on marginalized communities.

BOOZARY: Really, to me, what Covid has exposed is that the preexisting condition has been chronic neglect.

BRANGHAM: Dr. Andrew Boozary teaches public health and also works at a clinic serving people experiencing homelessness.

He argues the pandemic has been made worse by gaps in mental health care and financial support for Canadians.

BOOZARY: Really when you think about the brunt of who has had to be punished by our failure to do so, it's been marginalized communities, racialized populations.

And really, people living in poverty.

STAFF: Have you been in contact with anyone with those symptoms?

BRANGHAM: And then there's the issue of vaccines.

If there is anyone in Canada who should be near the top of the list for vaccination, it's 80 year old breast cancer patient Ruth Ann Wharram.

Her cancer care, she says, has been superb.

WHARRHAM: Out of this world, fantastic.

I have been so blessed.

BRANGHAM: But she, like millions of other older, medically vulnerable Canadians, was still waiting to get a vaccine in late-February, when we visited.

A complicated negotiation with vaccine manufacturers, and a failure to invest in its own drug production and delivery, put Canada far behind the US.

CC: "There's your guy."

RUTH ANN: "That's my doctor."

BRANGHAM: But Wharram's son, CC, whose a professor in the US, is glad his mother lives in Canada.

CC: With the death rates in the States compared to what we've had here, I guess I'd rather be waiting for a vaccine than have three times the per capita deaths, that's what we can sort of look at.

BRANGHAM: Ruth Ann was confident the vaccine issues would be smoothed out soon.

She told us how angry it makes her when she hears politicians in the US demonize her nation's healthcare system.

WHARRAM: Why wouldn't it make me angry?

I have this ability to go to a doctor when I need it, and not just me, but my next door neighbor who is working at McDonald's on a low income wage... Why are, is the system down in the States so adamant against it?

I can't understand that, I just can't understand it.

BRANGHAM: So, let's say the Biden administration comes to you and says, "Given the political realities in America today, what should we be doing that's feasible to get more people covered?"

CHENG: Most immediately we could help strengthen the Affordable Care Act, raise the income level of subsidies that you will give, so that this will allow more people to be able to buy health insurance.

That's number one.

Number two is that the administration should work with states, to expand.

Medicaid, the program for the poor.

Texas, Florida, North Carolina, and Georgia have not expanded Medicaid.

So, if we get one, or two, or three, or maybe all four, then we would have made big strides towards covering many more Americans.

Millions.

JHA: Look, we may never get to 100% coverage, but these policies alone can get us above 95, 97%.

That's pretty good, that's pretty good.

And if we can do that, and strengthen the ACA, we will be as close to universal coverage as the US is likely to get.

PRESIDENT BIDEN: It extends coverage and lowers healthcare costs for so many Americans.

BRANGHAM: Inside the enormous Covid Relief Bill signed by President Biden recently are provisions to strengthen the affordable care act and encourage more states to expand Medicaid.

But the ongoing political battle to adopt further changes, in both Washington DC and in state capitols, is a major one.

It was a major political battle in these other nations as well, but their experience shows that achieving universal coverage is not an impossible task.

BRANGHAM: Hi!

So nice to see you!

Just recently, we went back to Houston to check in on someone.

PARKER: It's good to see you again.

BRANGHAM: It's good to see you, too.

BRANGHAM: It's been a full year since we first met Lakeisha Parker.

BRANGHAM: You look fabulous.

PARKER: I feel good and everything is well.

A lot has been going on since the last time we met.

BRANGHAM: Parker is out of the homeless shelter, and in a new apartment... She proudly gave us a virtual tour.

PARKER: Welcome, welcome, welcome.

we're walking in, the kitchen is to my left.

My masks of course.

This is just my living area, cute enough for me.

My bedroom.

So grateful to decorate it the way I like it.

BRANGHAM: LaKeisha, the place looks fantastic.

PARKER: A great space, yes it is.

BRANGHAM: So you were in the shelter when the pandemic hit?

PARKER: We were literally in the shelter when we came up on shutdown.

BRANGHAM: Parker's back on her feet again after landing a job at an Amazon warehouse... it's hard, physical work, but she says she can do it for now and she's got health insurance.

PARKER: The last time I talked to you, I was homeless.

Since then, I have been blessed to work my way back to living life as what I feel is a productive citizen.

I have keys to my apartment.

(keys jingle).

I was helped to get keys to a car.

So things for me have changed dramatically.

They have really been on the up climb.

So I'm grateful, even though we suffered a lot of things.

BRANGHAM: I'm glad for, finally, some piece of good news coming out of this year.

PARKER: Yeah, for somebody.

BRANGHAM: One life changed for the better.

Tens of millions more are still in limbo.

Parker thinks America's health system can change...

But moving in the right direction... helping those in a tough spot avoid the struggles she's seen... simply because of one diagnosis... that's the task ahead.

But she has hope.

PARKER: Good things do happen.

It can't be like this always.

My life is a testament of that.

Homelessness, bad health...

But the sun is literally shining in my life today.

And I'm grateful.

I'm very grateful.

So this too shall pass.

This too shall pass.

BRANGHAM: Sun literally comes out as you say this!

PARKER: Yes, yes.

It won't be like this all the time.

This too shall pass.

(music plays through credits) ANNOUNCER: Funding for this program is provided by contributions to your PBS station from viewers like you.

Thank you.

‘I’m actually working in health care and can’t afford it'

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Special | 2m 58s | Critical Care: ‘I’m actually working in health care and can’t afford to pay it’ (2m 58s)

In UK, ‘No one says ‘that’s going to cost too much''

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Special | 2m 2s | In UK, ‘No one says ‘that’s going to cost too much, so we’re not going to do it" (2m 2s)

When a pandemic hits, does universal health care save lives?

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Special | 2m 40s | Critical Care: When a pandemic hits, does universal health care help save lives? (2m 40s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Major corporate funding for the PBS News Hour is provided by BDO, BNSF, Consumer Cellular, American Cruise Lines, and Raymond James. Funding for the PBS NewsHour Weekend is provided by...