Nevada Week In Person | Jackie Brantley

Season 1 Episode 77 | 14mVideo has Closed Captions

One-on-one interview with Jackie Brantley, Historic Westside Legacy Park Inductee

One-on-one interview with Jackie Brantley, Historic Westside Legacy Park Inductee

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Nevada Week In Person is a local public television program presented by Vegas PBS

Nevada Week In Person | Jackie Brantley

Season 1 Episode 77 | 14mVideo has Closed Captions

One-on-one interview with Jackie Brantley, Historic Westside Legacy Park Inductee

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Nevada Week In Person

Nevada Week In Person is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipMore from This Collection

Nevada Week In Person | Jamie Little

Video has Closed Captions

One-on-one interview with Jamie Little, NASCAR Broadcaster (14m)

Nevada Week In Person | Chet Buchanan

Video has Closed Captions

One-on-one interview with Chet Buchanan,Host & Creator, 98.5 KLUC’s The Chet Buchanan Show (14m)

Nevada Week In Person | Natalie Williams

Video has Closed Captions

One-on-one interview with Natalie Williams, General Manager, Las Vegas Aces (14m)

Nevada Week In Person | Randy Couture

Video has Closed Captions

One-on-one interview with Randy Couture, UFC Hall of Famer & U.S. Army Veteran (14m)

Nevada Week In Person | Fawn Douglas

Video has Closed Captions

One-on-one interview with Fawn Douglas, Artist and Activist, Nuwu Art (14m)

Nevada Week In Person | Brittany Force

Video has Closed Captions

One-on-one interview with Brittany Force, World Champion Drag Racer (14m)

Nevada Week In Person | Troy Heard

Video has Closed Captions

One-on-one interview with Troy Heard, Artistic Director, Majestic Repertory Theatre (14m)

Nevada Week In Person | Roger Gros

Video has Closed Captions

One-on-one interview with Roger Gros, Publisher, Global Gaming Business Magazine (14m)

Video has Closed Captions

One-on-one interview with Sharon Linsenbardt, Owner, Las Vegas Farm and Barn Buddies Rescu (14m)

Nevada Week In Person | Pilar Harris

Video has Closed Captions

One-on-one interview with Pilar Harris (14m)

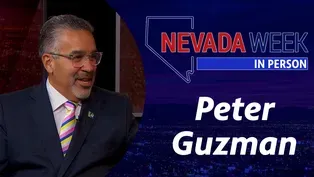

Nevada Week In Person | Peter Guzman

Video has Closed Captions

One-on-one interview with Latin Chamber of Commerce Nevada President & CEO Peter Guzman (14m)

Nevada Week In Person | Sam Joffray

Video has Closed Captions

One-on-one interview with Sam Joffray, President & CEO, Las Vegas Super Bowl LVII Host Com (14m)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipA native Las Vegan and pioneer for African-American women in Southern Nevada, Jackie Brantley is our guest this week on Nevada Week In Person.

♪♪♪ Support for Nevada Week In Person is provided by Senator William H. Hernstadt.

-Welcome to Nevada Week In Person.

I'm Amber Renee Dixon.

In the 1970s she became the first Black woman to oversee publicity and advertising for a Las Vegas Strip casino.

A recent inductee into the Historic Westside's Legacy Park, Jackie Brantley, thank you for joining Nevada Week In Person.

(Jackie Brantley) Thank you for having me.

-So you grew up in Las Vegas on the Historic Westside.

And at that time, it was segregated.

And I'm wondering, what about that time period and that era contributed to you becoming the trailblazer that you have become?

-Well, you know, I didn't see segregation as a little child growing up, because our community was almost self-contained.

We had many cultures in and out of the community, and we welcomed all cultures in the community.

We were fortunate to have many entertainers that frequented Jackson Street.

We had many professional people that, that entertained and also worked in the community.

So segregation could be more of a-- I won't call it a negative word, because when you're in an area, especially in an African-American neighborhood like that, it's like a melting pot.

But everybody in that community had something positive to do.

And we didn't, we didn't look at segregation as a bad word.

Actually, we had our own grocery stores, our own bowling alley, we had our own churches, schools.

And it was flourishing.

It was a flourishing Black community.

And as things changed and the community started to grow and people started to move out, then it became more of a thought process.

What is segregation?

What is integration?

But we really lost a lot when a lot of the people started to move out of that closely-knit community.

I don't see it as anything negative, but it did prepare me for what was to come.

It did prepare me for what was to come.

-How so?

-Well, you know, there were many protests in the community.

There was protests around the country.

And because my folks were avid readers and, you know, we did have news reports from what was going on around the country, we were aware of what was going on.

We had the voter rights.

We had civil rights.

We had a lot of things that happened after World War II.

Segregation.

People couldn't vote.

In fact, we didn't even get the vote till 1964.

But when we were able to vote, we were in line.

And the people in that community, they were representing.

And I was so proud to see that happen, especially when people like Martin Luther King would come to our community.

Our own minister-- -Do you remember that?

-Oh, yes.

I remember one of our minister, Reverend Marion Bennett, and one of our distant extended relatives, Virgie Fitzgerald, who is the wife of H.P.

Fitzgerald, also named in the Legacy Park.

They went out on the tarmac to meet him.

And it was in the Review-Journal, and we were all so excited.

And we were also aware that Las Vegas finally arrived, because now you're getting all of these national celebrities to come here and then to teach us how to do it and to work with us and to groom us.

And Las Vegas became a hot spot for that.

-You had told me off camera that you think people in that area right now need a pick-me-up.

-I do.

-To see someone like you.

Why?

-Well, you know what?

My first job as a five-year-old was taking out the trash.

And as I, you know, sprouted or, you know, hit the alley to drop off the trash cans, I looked up at the sky and I see one star.

And I would say, You know, I want to wish.

I'm going to wish for better things and wish for better times for the community.

And believe me, when you dream, dreams are there for plans.

So you just keep that hopefulness.

You keep that uplifting spirit, and you just keep going.

You don't ever stop, because there's always two positives to one negative.

And it's how you look at it.

So that's basically it.

Plus, you know, I had some help.

My grandparents were wonderful.

My Uncle Herman Moody was wonderful.

I had some great role models in the community.

-Your grandfather was a fixture in the community.

-My grandfather, he was-- we had a patriarchal society.

And not just in black communities, this was all communities.

And my grandfather was the grand patriarch, and everybody in the community respected him.

And of course we did.

And I was an observer of the elders.

I was an observer.

-What kind of impact do you think did he have on you?

-My grandfather, I mean I cannot say enough about him.

He needs a book himself.

And I probably would dedicate a couple of chapters to him in my book.

But I think, thinking about how he traveled from Mississippi, from McLain, Mississippi, 100 miles to the west, 100 miles to the west until they arrived in Arizona.

And they worked there in the lumber market for a while, and then they came to Las Vegas.

They were on their way to Oregon because there was work there.

And that was during the Great Migration.

Now, this little man, he probably was only about five-five, five-six with two kids, right, my mom Susie Moody-Parker, my Uncle Herman Moody.

And they just got in the car, and they went from McNary, Arizona, because that's the community that they were in, and they came to Las Vegas.

And the first day they were here, the car broke down.

So he wanted to go out and see, experiment, see what was the city like.

So he went to some of the casinos.

They were downtown, Las Vegas.

And there were Black people downtown at that time.

We're talking about 1939.

-Prior to the segregation.

-Exactly.

And then there was a substantial Black community downtown.

They owned their own property, their own businesses.

As a matter of fact, they bundled up with other Blacks that were moving through the Great Migration.

That's what they did, almost like the Underground Railroad, but it was not.

-For economic opportunity.

-Yeah, the opportunity.

And that night-- I'm not sure exactly.

It could have been the Las Vegas Club.

It could have been the prelude to Binion's.

But he worked.

And my mother and my uncle, they stayed in the car.

They waited for him.

And he worked for about five or six, seven hours, and he came back.

His pockets were heavy with, they call them "bow dollars."

They were silver dollars.

And his pockets were dragging around.

I said, Where you get that money?

Well, I work.

He said, I don't think we're going to be leaving right away.

So that's how it began for my family.

-Here's the problem, Jackie.

When I start talking to you, and I want to talk to you about you, you bring up everybody else.

-Yes.

I told you I was an observer.

-Yeah.

-So you know, and there's so many beautiful people that I grew up with in this neighborhood.

Every one of them deserve just as much attention as my grandfather and myself.

-Well, okay.

But I'm gonna stop you there because you're gonna continue.

I can just tell.

-Yes.

-Let's talk about you.

And you went from being a maid in high school to the Director of Public Relations at a Las Vegas Strip casino, one of the earliest African-American professionals on the Las Vegas Strip.

-Exactly.

-How did you do it?

-Well, there was this-- there's a story.

You need a couple of more minutes, right?

[laughter] -But I'll try to wrap it up.

Anyway, I worked as a maid during the summer months.

I went to Rancho High School.

That's where I graduated in 1966.

And it was a fun school to go to, you know, and I was prepared.

I was prepared to work and took a lot of honors classes in school.

I was a good student.

My mother was a school teacher.

But anyway, getting back to working as a maid, I could earn twice or three times the money that I earned working in the school cafeteria or working at the Guild Theatre.

I remember working there for The Cats, in high school.

And I was like, God, look at all-- I felt like my grandfather.

Look at all this money.

And I earned so much money, I paid for my wedding, I paid for my apartment, I paid for all my furniture, and I didn't even need any money from my mother.

I was like, Oh, my God, this money.

But then I thought, you know something?

I'm learning how to clean my house too.

And I'm also learning how to get through 13 or 14 rooms, and that was some hard work.

But I looked around and I saw other professional people doing it in the summer.

Teachers, because they didn't earn enough money as school teachers during the year.

That was a low paying job.

And I learned from them.

And I also learned that that is something I don't want to do for a living.

I need to get an education, I need to take myself to the next level, but this is honorable work.

And so I used that as a stepping stone, and I always remember and I never look down my nose on people who start out as maids or whatever.

But getting to the Desert Inn, the Desert Inn was only a couple of blocks away from the Westward Ho.

That's where I began.

So I was kind of used to getting out on the Strip, catching the bus or whatever to do to get to work.

And I said, Oh, my God, these hotels would have rooms too, but I don't want to do that kind of work when I get there.

-No.

No, you become Director of Public Relations at the Desert Inn.

You started there as a secretary, worked your way up-- -Yes.

- --where you're working around a lot of White male executives.

And you're a young Black woman.

-Yes.

-What was that like?

-Well, you know what?

I look at men as men, you know?

White, black, green, blue, whatever.

Man is a man.

And I tell you, in a patriarchal society at that time, women, you couldn't have, you know, own your own property for a while.

You couldn't do this-- it didn't matter if you were White or Black.

But at the same time, let's get back to it.

In our neighborhood, it was a melting pot.

We had White accountants.

Okay?

My mom worked as a bookkeeper.

The accountant would come to the house.

We had gaming executives.

There were hotels in the Historic Westside.

Some of them were run by people that were from, like, maybe the Asian culture, right?

Then there were individuals that were from all cultures.

I was, I was accustomed to that.

But working in that area, it didn't bother me because a man is a man.

And if he got out of line, I had to put him in check, right?

[laughter] -A couple did get out of line, and I had to put a couple in check.

I got a lot of respect for that, though.

-Did you ever have to put any celebrities in check?

-Yes.

-Because you worked with them at the Desert Inn.

-I did.

-Like who?

-Well, we don't want to leave-- Jethro.

What was it, Beverly Hillbillies?

-Uh-huh.

-Him.

He got out of line.

-Did he?

-Oh, yeah.

-How so?

-I'm not going to tell you.

I had to put him in check.

-We're protecting Jethro's reputation here.

-Yeah.

Is he living or dead?

I don't know and don't know if he'll remember that.

But anyway, there were times when I was in a tough situation.

But I find that if you respect yourself, then the respect will come from others, whether they're black, green, blue, or whatever.

Mm-hmm.

-Your career also included some modeling?

-Yes.

-An appearance in Ebony magazine.

But that was not related to modeling.

What was that?

-No.

No, it wasn't.

That appearance in Ebony was announcing that I was the director of advertising and public relations.

There was an article written by Elliot Crane.

He was with the Las Vegas Today.

And he found it fascinating that I was a maid and that I was working at the Desert Inn.

He said, Can I do a story?

I said yeah.

So he sent the story from the Las Vegas Today to Ebony magazine.

Then they contacted me and said, Hey, you know, is this true?

Yes.

And then I was outside the Desert Inn in front of the pylon, which Wayne Newton was appearing, and he-- and one of my jobs was to help them create a feather, because that talked about his heritage.

-Okay.

-And so Wayne Newton's name was on the billboard, and I was in front.

And that was my job, to make sure that pylon was correct and that the entertainment got out and that the advertising got paid for.

So you know, it was a thrilling job.

It was-- -Talking about another job.

We have one minute left.

-Sure.

-You worked under former Governor Kenny Guinn.

-Yes.

-Communications director as well as community relations?

-Constituent services director.

-Big job!

-Yes.

-What kind of impact did he have on you and you on him?

-Well, I worked with the Clark County School District from 18 until after I got married, had my children.

I worked for the Clark County School District for eight years.

And there I was around a lot of educators.

And Kenny Guinn was the-- he was the manager in school facilities.

He was in a-- then he became the superintendent.

-So you knew him then.

-Yes.

So we worked closely together.

One thing we had in common.

-What?

-We both drove Volkswagens.

We were frugal.

He was a numbers cruncher.

I was a numbers cruncher.

And so he remembered me working with him at the School District.

He followed my career, and then he moved my desk from DMV into the governor's office.

There you go.

-Jackie Brantley, thank you so much for joining Nevada Week In Person.

-And for more interviews like this, go to vegaspbs.org/nevadaweek.

♪♪♪

Support for PBS provided by:

Nevada Week In Person is a local public television program presented by Vegas PBS