Where the Pavement Ends

Season 8 Episode 1 | 1h 19m 2sVideo has Closed Captions

A haunting look at the deep and lasting wounds of segregation and racial injustice.

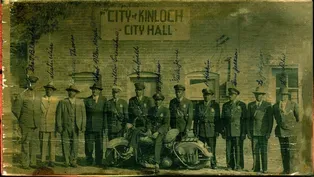

Transporting viewers to Missouri towns - then all-Black Kinloch and the all-white community of Ferguson, examining the shared histories and deep racial divides affecting both. Through recordings, photographs and recollections, WHERE THE PAVEMENT ENDS draws parallels between a 1960s dispute over a physical barricade erected between the towns and the 2014 shooting death by police of Michael Brown.

Major funding provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. Additional funding provided by the Wyncote Foundation, the National Endowment for the...

Where the Pavement Ends

Season 8 Episode 1 | 1h 19m 2sVideo has Closed Captions

Transporting viewers to Missouri towns - then all-Black Kinloch and the all-white community of Ferguson, examining the shared histories and deep racial divides affecting both. Through recordings, photographs and recollections, WHERE THE PAVEMENT ENDS draws parallels between a 1960s dispute over a physical barricade erected between the towns and the 2014 shooting death by police of Michael Brown.

How to Watch America ReFramed

America ReFramed is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipMore from This Collection

Video has Closed Captions

The remarkable life of a fearless Mississippi sharecropper-turned-human-rights-activist. (58m 41s)

Video has Closed Captions

Sol Guy watches his late father’s tapes -- and confronts the choices of his father’s life. (1h 19m 25s)

Video has Closed Captions

Off the Georgia coast, two brothers grow up in an enclave of the Saltwater Geechee people. (1h 31m 22s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipRANDALL GUNTHER: This is the border between Ferguson and Kinloch.

NATASHA DEL TORO: Two towns in Missouri, separated by race.

JOHN BRAWLEY: Well, Ferguson, uh, we'd just as soon not get too close.

DEL TORO: From segregation in the 1960s to the 2014 police shooting of Michael Brown, reckoning with racial injustice in America.

MAN: Enough is enough!

DEL TORO: "Where the Pavement Ends," on America ReFramed.

♪ WOMEN (on recording): ♪ Farewell ♪ Farewell, fare thee well ♪ Fare thee well DORIAN JOHNSON (dramatized): Like I said, we were walking down Canfield.

We made it down two or three blocks before we hit the leasing office, and that's the beginning of the apartments.

DOROTHY SELTER: And you gotta remember, in the late '60s, we were... LARMAN WILLIAMS: Business as usual.

SELTER: Probably 99% white.

JOSEPH WELLS: There was near 15,000 people living in Kinloch.

JOHNSON (dramatized): Like I said, we're about two or three blocks down.

WILLIAMS: Yeah, I've heard stories about Ferguson... JULIA BOYD: Recommended that we write a letter to the Civil Rights Commission.

WILLIAMS: ...being a sundown town.

(multiple voices overlapping) DOROTHY SQUIRES: And they had passed all of that hatred and prejudice on to their generations.

DONALD HARRY: On my community... SQUIRES: It's just been perpetuated.

HARRY: This did not need to come down like this.

Tore the houses up.

(multiple voices overlapping) (police radio squawking, woman singing) THEODORE HESBURGH: And yet there's a link between these hearings, as there are between all commission hearings.

(police radio and singing continue) SELTER: A number of people wanted the wall to come down.

(singing fades) JULIA BOYD (dramatized): Alas, I have been daydreaming.

READER (as herself): Let me start over.

BOYD (dramatized): Alas, I have been daydreaming.

(people talking in background) (people talking, music playing in distance) (people talking in background, crickets chirping) (baby babbles) (police siren blares) HARRY: I guess they're just going to let that burn to the ground.

I'm just, I'm just heartbroken right now.

Um...

I'm, I'm heartbroken for the parents of the child that died yesterday, I'm heartbroken for my community.

I'm, I'm heartbroken for my city.

This did not need to come down like this.

But I guess things being the way they are, people just, frustrations just boiled over.

It's just, um...

I wish they would have, that they could've found a better way to express themselves, other than tearing up their neighborhood.

(fire crackles) Because like I said, when it's all said and done, we still gotta live here.

We still have to live here.

(reader clears throat) "Alas, I've been daydreaming.

"As I awake from the dream, "my heart begins to bleed again, "for in my heart, "I know that too few will try.

So what do we say to the rioters?"

(birds chirping) ♪ ♪ (man singing country ballad) (birds, crickets chirping) (song continues) (motorcycle revving in distance) (people laughing on old recording) GIRL (on recording): Ladies and gentlemen, I'm going to sing this song... (giggles) ...to Marisa Peebles and Andrew Whales.

"Your Precious Love."

(girls laughing in background) (laughter continues) (laughing): ♪ Your... ♪ Your... (girls laughing in background) ♪ Your precious love ♪ Means more to me (girls laughing in background) ♪ Lonely teardrops, yah!

♪ You never could be mine (girls laughing in background) That's right, get outta here, all of you bumbles.

Go on, y'all.

(player stops) (keys jingle, car starts) BOYD: So where did you live?

You said in Ferguson?

JANE GILLOOLY: Yeah, I grew up on Royal Avenue in Ferguson, just a block over from the Saint John and James Church.

BOYD: Okay.

GILLOOLY: About a mile or so from the border of Kinloch.

♪ GILLOOLY (on phone): Julia, where did you live when you lived in Kinloch?

BOYD (on phone): On Wesley Street, 8217 Wesley.

GILLOOLY: Have you been through the town at all since they started tearing everything down?

BOYD: Oh, yes, yes, several times.

My mother has lived there until about 1994, and then after that, her house was torn down.

♪ My mother lived to be 102 years old.

And... she didn't like to get out so much, but if I would say to her, "Well, let's just drive through Kinloch," she would say, "Okay."

And we would do that.

And we would point to landmarks there.

Sometimes it was just a matter of remembering the trees that were in the yard.

GILLOOLY: The road closing between Ferguson and Kinloch.

BOYD: Yes.

GILLOOLY: That's a piece of this puzzle that I've been trying to put together.

(metal clanging in breeze) BOYD: The march to remove the barricade, uh...

I had to really think about that.

At the time, I was working at the Kinloch Gateway Center.

GILLOOLY: Mm-hmm BOYD: And our advisory board had undertaken that project to see if we could get the City of Ferguson to remove that barricade so that the traffic could flow between the communities easily.

(birds cawing) (car approaches) JAY WILL: This is how I've always seen Kinloch.

Ghost town.

Some of these streets don't even come on Google Maps no more.

(birds chirping) I started driving when I was 16.

That was in the '90s.

And once you drive through here in the '90s and early 2000s, it always looked kind of ran down.

But you always heard the stories about how prominent it was.

(airplane passing overhead) These towns, we could have them again, but, you know, I think, I think it breaks people confidence when they hear how it ended.

Because it's the same story every time.

(recording begins playing) (slide carousel clicks throughout) HESBURGH: The United States Commission on Civil Rights is an agency of the United States government.

Its duties are as follows.

To study and collect information regarding the denial of equal protection of the laws under the Constitution by reason of race, color, religion, or national origin.

This hearing of the United States Commission on Civil Rights will please come to order.

MAN: The next witness is Mr. Conrad Smith.

WOMAN: Mr. Smith, will you raise your right hand, please?

Do you swear to tell the truth and nothing but the truth?

CONRAD SMITH: I do.

WOMAN: You may be seated.

MAN: Mr. Smith, would you identify yourself, please?

CONRAD SMITH: I'm an attorney with the Office of General Counsel, United States Commission on Civil Rights.

MAN: Mr. Smith, I have a document, uh, United States Commission on Civil Rights staff report, Kinloch, St. Louis County, Missouri.

Madame Chairman, may we introduce this into the record?

WOMAN: So ordered.

MAN: Mr. Smith, would you please summarize this report for the commission?

CONRAD SMITH: The commission staff report on Kinloch, Missouri, indicates that the city faces a number of substantial problems.

Kinloch is an all-black, politically independent city, located in suburban St. Louis County, approximately seven miles northwest of St. Louis city limits.

Although the city is surrounded by the predominantly white communities of Berkeley and Ferguson, it is sharply separated from them.

Apart from one main road and several secondary access routes, large vacant lots and fences serve to seal off Kinloch from its neighbors.

CONRAD SMITH: Most streets in surrounding areas dead-end at Kinloch.

BOYD (dramatized): In April 1968, shortly after the death of Martin Luther King, Jr., several leading citizens of Kinloch led a march to the site of a barricade which had been erected by citizens of Ferguson and which blocked one of the few roads to the city.

(airplane flying overhead) (radio playing) (sniffs) SQUIRES: Now, are you aware that at one time, this was called Kinloch Park?

And it was North and South.

I don't know if you're familiar with that or not.

Are you?

(sniffs) And then the north section broke away from Kinloch.

They became Berkeley.

And, uh, then it just remained Kinloch, as opposed to Kinloch South.

That was before my time, that's, um, you know, just the history that I know.

Are you aware the street that was closed off into Ferguson?

Have you been over there?

GILLOOLY: Well, tell me about that.

SQUIRES: Okay, I'm going to show you where that, that is.

It's on Suburban.

And, uh, we could go into Ferguson on the upper end.

Down near the Suburban area, they had that blocked off, because that kept us out.

There were just houses all over here.

This is it, right here.

Probably the City of Ferguson, I would assume that's who put the barriers up there.

I just remember it having something across the road, I don't know whether they were, like, uh, concrete columns or wooden columns, I just don't remember.

It was a little bridge or something that went over there, but I just remember the cars couldn't go through there.

(directional clicking) It separated Kinloch from Ferguson.

GILLOOLY: When did it open?

- Now, that, I don't know.

(phone calling out) JOHN WRIGHT: Hello?

GILLOOLY: Hello.

WRIGHT: Yes, how are you doing?

GILLOOLY: Hi, I'm very well.

So the photo that you have in your book is one that you, you took yourself?

WRIGHT: I took that myself, yeah.

You can see the trees were still kind of bent.

GILLOOLY: Uh-huh.

WRIGHT: Almost kind of opened that kind of... it made a nice photograph.

GILLOOLY: It's a beautiful photograph, actually.

Do you have any photographs of it when it was, when it was blocked off?

WRIGHT: No.

After protests, during the '60s and the King demonstrations, and, they decided to open up the road.

But they had debris put in there and asphalt piled up, along with a chain.

(insects chirping loudly) RANDALL GUNTHER: We are standing at the extreme southwest corner of the city of Ferguson, Missouri, at the intersection of the street named Suburban and a street named Mueller, respective to the farm at the north end of the street that's now an organic farm school.

This is the border between Ferguson and Kinloch.

Kinloch is a traditionally segregated black community.

This road was part of segregation.

It was blocked from through traffic by obstructions in the road.

(machinery whirs in distance) The border was blocked by trees planted called Osage orange, also known as hedgerow.

The trees are noteworthy because of the extremely large thorns.

Very effective on preventing animal, livestock, or human traffic wherever this hedgerow was planted.

GILLOOLY: Is there any of it left?

GUNTHER: Oh, yes.

Very much of it.

(birds, insects chirping) PETTY: Used to be a block barn there.

Uh, he tore it down, mostly.

The house is down here.

(traffic passing) Come a little bit closer.

Can you see it better there?

(birds chirping) Hmm, nobody walked through this path.

Let me see, oh, let me see, can you see...

I'm more worried about... You see the top of the roof of the house?

MAN: Yeah.

PETTY: Right?

If you come right here-- can you come right here?

MAN: I can see it.

PETTY: Okay, you see the roof of the house?

GILLOOLY: Eric, isn't it strange to be standing here, where there used to be thousands of people living?

PETTY: All down this street were wall-to-wall houses.

There's another, there's another house down there.

It is thick of forestry down that way, another half a block to the left.

I used to cut a path here to the barber shop, but since the apartments closed, nobody don't go over there.

GILLOOLY: Do you miss the community?

PETTY: Yeah, you miss it.

But we better head back, I'm worrying about why.

I don't like that sound.

Can you come on back, guys?

MAN: Would you like to have her arm on the table?

BOYD (clears throat): Well, I, I thought he wasn't filming me.

GILLOOLY: The computer is what he's filming.

BOYD: Okay.

MAN (archival): Would you please state your name for the record?

BOYD (archival): Julia Boyd.

MAN: How long have you lived in Kinloch, Mrs. Boyd?

BOYD: With the exception of three years, all my life.

MAN: Mrs. Boyd, what is your occupation?

BOYD: I'm coordinator of the Kinloch Gateway Center.

MAN: Mrs. Boyd, we have some pictures of Kinloch, and I wonder if you'd identify them for the commissioners.

BOYD: Uh, this is a picture of a substandard house in Kinloch.

It may or may not have running water.

There would not be a sewer attached to this home.

There may be indoor toilet facilities, or there may not.

And it is not atypical.

This is a house in Rushmore Park, one of two subdivisions.

Some of the better housing in the community.

Some people like to say that, uh, blacks don't, you know, take care of things that they have.

That subdivision has been there for approximately eight years, and it's as nice as any you would find in St. Louis County.

(slide carousel clicks) This picture was taken from the Ferguson side at a point where Kinloch and Ferguson border.

The sign says, "Pavement End."

The paved road runs out of Ferguson, and then you have a beat-up road which comes on into Kinloch.

And it's typical of the, uh, racial and physical isolation of that community.

Uh, and it's very depressing, disheartening for the children to have to grow up where they feel that, you know, where they live is so different from where children in other areas live.

To have a child close his eyes when you're getting ready to move into Kinloch, and say, "I bet I can tell you when I get there, because, you know, I'm gonna hit this bumpy road."

It's a game we played when we were kids, it's a game that the kids still play today.

But, you know, it's not so funny, because when you really stop to think about the reasons why this has happened, you know, it's no game.

We want our children to go to school, return to the community, and make a contribution there.

BOYD (present-day): I actually lived right in the center of Kinloch.

I tell people all the time, what you heard about Kinloch is not what Kinloch was.

People made up a lot of things about Kinloch.

We never had to lock our doors.

We just came home and opened the door and came in.

We probably didn't realize how blessed we were as kids, but as we got older, we realized what a treasure we had.

HESBURGH: The choice of site for this hearing was not by chance.

Situated as it is in St. Louis County, but physically close to the city, offers an appropriate setting to have this hearing that will touch on both the city and the county.

In the '50s and '60s, our suburbs have sprouted like mushrooms after a summer rain, while our cities have wilted in the dryness of neglect.

Most white Americans have been free to leave the concrete city for what they regard as a better life in the open spaces of the suburbs.

But the poor, and primarily the black poor, have been trapped behind the invisible wall that divides city from suburb.

The movement has been not only of people, but of jobs, as well.

And this twin tide of out-migration has tended to push us further toward the tragedy of two separate societies, one white and comfortable and one black and poor.

And unless the barriers to those areas are overcome, the advancement we have made on the civil rights front will have little meaning.

GILLOOLY (on phone): Well, so you said you've been in Kinloch about a year ago?

WRIGHT: Yeah, I drove through, and it's all, pretty much all gone.

GILLOOLY: Well, yeah, I mean, I did drive through, the cinematographer, and we shot some footage of the, of the roads.

You know, it's very pastoral now, and rural, and it was, you know, between the airplanes flying by, there was, you know, beautiful bird sounds.

WILL: Yeah, it's going to be part of an industrial park.

(machinery beeping) SQUIRES: I could go up there... (muttering) Now, see how low the planes were coming over in Kinloch?

When I was 14 or so, a plane crashed, and it was a...

I think it was, like, a test pilot.

He was the only one in the plane.

And we all ran because we heard the... We heard the crash and... Of course, we all were outside playing, so we ran up to what used to be the feed company there, up on that hill.

And, uh, you could see the parachute hanging in the tree.

It was really kind of frightening, you know?

Like, I'd never seen anything like that before.

But the planes came over so low on, uh... over Kinloch, this end, that uh, it was always noise.

We just kind of got used to it, you know?

Wonder if I could go up there... (muttering) And the movie theater was...

It's hard to tell, because everything's just about gone.

Okay... ♪ Um... We got what we wanted, which was the freedom and the ability to go places and buy homes and stuff.

But we lost what we had.

(birds and insects chirping) (airplane passing overhead) PETTY: 17 minutes, we'd be counting.

You get used to it, the only time, you know, like, the only time people look up... (chuckles) I hate to say it, when the helicopter's flying around, the police are pissed off, getting somebody.

That when the dog's, everybody else is looking down.

When that helicopter, looks, and... "Oh, Lord, they chasing somebody, they got somebody," 'cause we hear that chopper.

When we hear that chopper, everybody, even the dog, even my dog will look up.

"Oh, Lord, they're chasing somebody."

You're hearing sirens and helicopters, that when everybody looks up-- plane?

That's like driving a car, they don't pay no attention.

GILLOOLY: So, your dad, was he an architect?

PETTY: He was an architect, and he, uh, went to Detroit and learned the trade, and came back.

Yeah.

Yeah, I got a lot of antique stuff.

Toys, like toys, they 50 years old.

I'll, I'll take you through this way.

Lord, guys... (exclaims) Come on.

The plans in here, lady, and I don't know where they at.

This was the office back in the day.

Come on in.

I got to look for the plans somewhere in here, lady.

I've gotta move this.

I've got to find where the plans at in here.

GILLOOLY: Oh, so, your dad's plans?

PETTY: Yeah, yeah, he was an architect.

He had a big desk...

He had a big... Where's the bigger drawing board?

Might be in the other section.

I don't know where they at.

Okay, these are old envelopes and stuff...

I don't know what this is.

I don't know-- wait a minute, I need my glasses.

Wait a minute...

I don't know where he left, we gotta read, I gotta read.

I gotta read-- I don't know what plans are these.

I'm trying to save them...

These are, these are some of them right here.

Mm-hmm.

Signed, yeah, these are it.

Come on in here.

And the shutters, yeah, wait a minute, that is, my father did draw them.

It says right here, it says, William M. Petty Design.

(traffic humming in distance, birds chirping) He built the junior high, that was the city hall.

He built Smith School.

He built the Firewells Apartments on Suburban.

GILLOOLY: He built all over?

PETTY: Yeah.

Everything, basically, was brick around here... GILLOOLY: Mm-hmm.

PETTY: He built it.

(airplane passing overhead) GILLOOLY: How much time have you spent in the town?

WILL: In Kinloch?

Um, I'm just familiar with Kinloch because I grew up in North County a lot.

You know, I'm not from there, but...

It just has an interesting history.

(electronic bells playing) I just find it funny that a lot of the people that came, that came to Kinloch, came from East St. Louis.

(chuckles) They came from East St. Louis running away from white terrorism.

And then when you get here, decades later, they, they have to migrate again, you know?

It's interesting, like... My kids, I bathe them in blackness.

That way they have confidence in theyself.

Blacks got to bathe their kids in blackness, because once you walk out that door, you're dealing with white supremacy.

In the home, you have to bathe them in blackness, so they have some pride about theyself.

Everything was black-owned.

They didn't even have to leave Kinloch.

They had everything there.

I'd really like to see that again.

JOHN BRAWLEY: There are some things that are very controversial, and one of them was a street that had always been closed in Ferguson.

And the reason it was closed was that on the west side of the city is the city of Kinloch.

And Kinloch is all-black-- I mean, an incorporated city that's all black people.

Well, Ferguson, for all of its goodness about many things, we'd just as soon not get too close to Kinloch.

(birds chirping, airplane droning overhead) (phone calling out) BOYD: Hello.

GILLOOLY: Oh, hello, Julia, this is Jane Gillooly.

BOYD: Yeah, hi, Jane, how are you?

GILLOOLY: I'm good, um, is this an all right time to talk?

BOYD: Well, I'm expecting someone to pick me up-- my son is supposed to pick me up, so he may or may not come at any moment.

GILLOOLY: Okay.

The road closing between Ferguson and Kinloch?

BOYD: Yes.

GILLOOLY: Can you tell me what you know about that?

BOYD: Things were done deliberately to isolate the city of Kinloch.

GILLOOLY: No one could remember when the barricade was put up?

BOYD: No, I don't remember that.

GILLOOLY: So you just remember it kind of always being there?

BOYD: Yes.

WILLIAMS: It was there.

All we knew, it was the cut-off point dividing Kinloch and Ferguson.

(puddle splashes) BOYD (on phone): I remember that it was closed, and there was a wall or a fence, or something down there.

GILLOOLY: Can you describe what the barrier looked like?

SELTER: You know, I don't remember.

Uh, there was no reason to go down there.

There was just a few houses down there at that time, on this side.

But, when I look back at that, we never talked about the hard stuff.

And it's the hard stuff that's coming out now.

NOEL COOKSON: I think there was some sort of divide.

Wasn't there?

Or maybe there was a fence, but like a... One of those corrugated steel guardrails they put up on roads.

LARMAN WILLIAMS: Nobody ever gave us any official information as to why that barricade was up there, or that blockade was up there.

GILLOOLY (on phone): A pile of rubble and concrete... To keep Kinloch people out.

GILLOOLY: So you said you were born in '47, but the road was blocked before that.

PIERCE CARTER: Yeah, that was closed right there.

I'm pretty sure it was like a swinging gate, you know.

That's what I'm thinking.

And at dark time, we better be out of there.

All blacks, riding three or four deep, locked down-- they was on the side of the street.

The police, they want you out, at dark.

"What are you doing over here...

nigger?"

There wasn't no sugar-coating it.

You know, "What you coming for?"

And you had to tell them.

That's before the boy got killed.

I'm talking about from '50s, '60s, up until '70s, they've been like that.

City of Ferguson ain't, they ain't just, uh... That Brown thing, that stuff was boiling for years and years and years and years.

It just wasn't nothing just happened overnight.

It ain't changed, it ain't going to change.

MAN: Is there any one particular incident that took place during one of your terms as mayor that you think you'll never forget?

BRAWLEY: Kinloch asked if, um... Their mayor asked me if, um, we could open the street so people could come through and you'd have traffic, through traffic.

Not necessarily they wanted to come to Ferguson, or that we'd want to go over there, but to make it through traffic, and I said, "Of course."

"Well, how about taking the barricade down?

We can get the ditch fixed."

So I said, "Of course, we're not gonna, keeping anybody out.

Take it down."

All hell broke loose.

(chuckles) Because some people didn't want it done.

(crickets chirping) BOYD: To live in that area of Kinloch, and you want to get over here, it's insulting.

You've got to drive all the way up here to the north end of Kinloch and go through several blocks in Ferguson, then come down to the main street and get to where you want.

That barricade, I mean, it was definitely something that said, "Don't cross here.

You're not welcome."

GILLOOLY: We haven't spoken in a few years, but I did grow up in Ferguson, and, you know, as a child, remember the barrier.

Not that anyone ever told me why that barrier was there, but you knew why that barrier was there.

You knew it was offensive... BOYD: Mm-hmm.

GILLOOLY: And it was there to keep people out.

BOYD: Right.

So when it was finally taken down, I was pleased that it had happened and to have been a part of that.

RADIO ANNOUNCER: Just in, Dr. Martin Luther King was shot outside a Memphis hotel this afternoon.

His condition was not immediately known.

The shooting took place near the Lorraine Hotel... BOYD (dramatized): In April 1968, shortly after the death of Martin Luther King, Jr., several leading citizens of Kinloch led a march to the site of a barricade.

(footsteps tapping, voices whispering) JOSEPH WELLS: The march started at the school.

Because if I'm not mistaken, it started at the school.

And moved from the school down, which was Carson Road at the time, and then around to Suburban Street.

AMANDA SMITH: Yes, we did organize that.

Julia and the people at the Kinloch Gateway Center.

And we planned that Martin Luther King march from Kinloch over to, um, one of the churches in Ferguson.

And I remember people on that other side ignoring that, but they didn't like it.

They didn't want us coming over there, over to that area.

But we went anyway, and it didn't have any problems that day.

(footsteps and murmuring continue) BOYD: I participated in it, but you know when we first talked about that, Jane, I had some difficulty remembering what went into it.

GILLOOLY: Do you remember the letter that you wrote?

BOYD: Some of that sounded like how I might have expressed myself, and some of it didn't.

I noticed in the letter that I mentioned something about the short period of time before requesting use of the church, right?

I don't know that I could... BOYD (dramatized): April 16, 1968.

Dear Reverend Roth, As you might know, plans for the memorial march were made in about four hours at two impromptu meetings, and therefore, it was impossible to request the use of your church earlier than we did.

May I say that because you did not hesitate to make your church available, a healing salve was placed on an open wound in my heart-- not the new wound caused by Dr. King's death, but the old one that gets deeper and wider with each new disappointment.

Perhaps I bleed too easily, and this is my sickness.

It is better to bleed than to have the sickness of those who inflict the wounds.

(footsteps tapping slowly) JOSEPH WELLS: The blacks and the whites in Ferguson, they didn't have nothing to do with each other, you know.

Things were real prejudiced then, you know, in '68.

BOYD: Um, the isolation that was drawn by the fencing and the barricade at the end of the road, the bus where you had to sit in a certain place-- it was just all around you all the time.

But you always felt so safe in Kinloch.

And it was when you went out of the community that you began to see all these other things that were targeted at you because you were black.

GILLOOLY: Do you think maybe there's any correlation between Canfield, I mean... BOYD: I just think it's...

It was there, it is there, and...

I would not know how to have a direct correlation between what happened on Canfield with Michael and these other things that I've described except to say, if it's in somebody's heart or in somebody's head that they're better, then these things are likely to happen.

I don't want draw in today's current events... BOYD (dramatized): The Negro has been brainwashed thoroughly enough to appreciate already white beauty, white culture, white finery, and white ability to get to the top.

We should take time to study why white people have superiority complexes, violent natures, create conditions which cause riots, have no respect for the dignity of mankind, are so clannish, etc.

When we get our answers, we must love in spite of our differences.

Then, after doing our homework, let us examine our consciences, make changes within human limitations.

This could be done overnight, each person willing.

JOSEPH WELLS: We ended up getting it, getting it cleared out at the end, but it still was a real contentious matter between Ferguson and Kinloch, you know.

AMANDA SMITH: But there was always something going on.

People got together, and I know, at the end, we got through the day okay.

BOYD: One thing that I remember is that we were angry.

And today, people are angry.

There are a lot of things to be angry about.

And a lot of people don't get it.

And they think that not only do you have all day to work your way through it, you've got the rest of your lives to work through it.

And that's not true.

We want what everybody else has now, just like they've got it now.

MAN (archival): Could you speak in the microphone, please?

MAN: The next witnesses are Mr. and Mrs. Larman Williams.

Mr. Williams?

WILLIAMS (archival): My name is Larman Williams.

I live at 21 Buckeye Drive, Ferguson, Missouri.

I'm the assistant principal at Halter High School in Wellston, Missouri.

MAN: Why did you decide to move to the city of Ferguson?

What led you to Ferguson?

WILLIAMS: Well, first of all, I had some knowledge of the community.

I'd lived close by there, I grew up in Kinloch, which was an all-black community, and used to drift over in Ferguson, looking at those lovely houses over there, when they were all segregated.

Generally, I wanted, uh, to find a home, and I wanted to locate in an area where I could get the best facilities for the amount of money that we were paying, and, uh, fire services, police protection, where the crime rate was low.

Like any other citizen would want.

MAN: Did you encounter any difficulty in making the purchase of your home?

(phone ringing in present day) WILLIAMS: I most certainly did.

MAN: Would you describe it for us, please?

WILLIAMS: Yes, um... After looking around, for a year or so, my pastor-- who, incidentally, was a white fellow-- found out that we were looking for a place, and he lived over in this area, and he saw two or three places for sale, and asked me if I would like to live in Ferguson.

He took us by this particular house over on Buckeye, and we thought we'd like to get inside and see it.

We took the name off of the sign and called the real estate people, but the real estate people wouldn't, wouldn't call us back.

MAN: How long did it take you before the whole transaction was finally completed?

WILLIAMS: I imagine it was about six months.

MAN: Took some special doing-- it wasn't, you're just wanting to buy a house and buying it.

WILLIAMS: That's correct.

GIRL (on recording): ♪ The time has turned its back on me ♪ ♪ The time (laughs) ♪ Has turned its back on me ♪ The time has no sympathy ♪ Now the time ♪ Has taken my love (birds chirping) (crickets chirping) FANNIE WELLS: Anything that's swept under the rug in the beginning, as long as that stays covered up...

It's gonna have a smell, and that smell comes out, and will rotten up everything, and gonna weaken up, until that is all cleaned up.

It's gonna be a, a battle, mm-hmm.

(bike pedals churning) POLICE OFFICER (over radio): Frank-25.

DISPATCHER (over radio): 25.

POLICE OFFICER: I'll be 10-8 and I'll head over to Victorian Plaza.

DISPATCHER: Okay, we're taking a stealing in progress from 9101 West Florissant.

Subject may be leaving the business at this time.

Stand by for further.

POLICE OFFICER: All clear, I'm right here.

DISPATCHER 2: 25, it's going to be a black male in a white T-shirt.

He's running toward QuikTrip.

He took a whole box of Swisher cigars.

POLICE OFFICER: Black male, white t-shirt?

DISPATCHER 2: That's affirmative.

POLICE OFFICER: I don't see anybody running out here.

DISPATCHER 2: She said he was walking.

That he headed up toward QuikTrip from 9101.

POLICE OFFICER: Does she have any further?

DISPATCHER 2: Negative.

POLICE OFFICER: There's nobody walking out here with a white T-shirt.

22, I'm hitting you with a report from the last.

Do you have any further description on that?

Male, I have, uh...

Male with a white t-shirt, black pants, and a backpack on Sharondale.

POLICE OFFICER 2: He's, uh...

He's with another male.

He's got a red Cardinals hat, white T-shirt, yellow socks, and khaki shorts.

He's walking up... (radio crackles) If we have detectives on duty, they need to respond, as well.

DISPATCHER 1: 25?

POLICE OFFICER 2: Get us several more units over here.

There's going to be a problem.

DISPATCHER 1: Can any available Ferguson units who can respond to Canfield and Coppercreek advise?

Ferguson, St. Louis County, do you have any-- possibly at Dellwood or St. Louis County-- officers available for crowd control and disturbance to assist Ferguson, Canfield and Coppercreek?

POLICE OFFICER 3: I'm right behind you.

PROTESTERS (chanting): The people, united, will never be defeated!

The people, united, will never be defeated!

FANNIE WELLS: This generation's strong.

These youngsters are fighting for us that didn't say nothing.

They fighting for us.

So I say go ahead-- why?

Because they got the guts to step out.

Yes.

♪ JOHN WRIGHT (on phone): African Americans could start buying homes in different communities.

Our housing did open up for African Americans.

GILLOOLY (on phone): So what part of Ferguson did black families move into?

WRIGHT: Section next to Kinloch, the main part first.

Then in other sections.

Race-restricted covenants were lifted.

The realtors decided what part of Ferguson would be a place to move blacks in to.

What neighborhoods were going to be black, which neighborhoods were going to remain white.

DAVID WHITT: We're in the third ward right now, okay?

And we're getting ready to cross over there to the first ward, and then you going to see... You're going to see what the neighborhoods look like.

But I'm going to show you, also, it's black people that live over there, as well, but the houses is different, the policing is different over there.

Though it may be, it may be black people living on the other side of Ferguson, where all of the white people live.

The black people, I talked to some black folks that live over there, and they still get harassed by the cops.

The white folks don't get harassed like that.

Ferguson is broke down in, I believe, three wards.

But it's broke down with a racial divide line.

This is where a lot of the white people live at.

A lot of them is just disconnected with what's actually going on.

Some of them are still in denial that Ferguson police even acts like this, because they don't...

They don't encounter the same type of police that we do.

SELTER: Long about, um... the late '80s, early '90s, there was an influx of black residents.

Prior to that time, we seldom saw a black person, even though our neighboring community is Kinloch.

Many, many people moved out.

The white people moved out because they were afraid that Ferguson was going to become a ghetto.

(car engine humming) GPS: Turn left onto Suburban Avenue.

(woman singing faintly, directional clicking) GPS: Continue on Suburban Avenue for one mile.

(singing continues) (woman whispering in background) GPS: In 1,000 feet, turn right onto Ferguson Avenue.

(woman whispering in background, woman singing in car) GPS: Turn right onto Ferguson Avenue.

(woman continues singing) HOWARD O'GUIN: With the segregation in the county, we was forced to build houses in Kinloch or leave the area completely, you know, because we were not allowed to build in these white communities.

But when people began to get better jobs through the government pressure on these corporations to put blacks into meaningful positions, they had more money, so they wanted to be, be able to find a nicer home or a better school district than what was offered in Kinloch.

(mower running) GPS: In 1,000 feet, turn left onto West Florissant Avenue.

BOYD: I think most people stayed in North St. Louis County.

So that would have been Berkeley, Ferguson, Florissant, and some areas of unincorporated St. Louis County.

GPS: Turn left onto West Florissant Avenue.

O'GUIN: That's what caused the drop in population in Kinloch, because people who could afford to leave began to leave.

GPS: In 1,000 feet, turn right onto Canfield Drive.

In 800 feet, you will arrive at your destination.

You've arrived.

JOHNSON (dramatized): Um...

When we were walking back at the time, we were on the sidewalk.

The street was clear-- it was just clear.

We were having a conversation.

It was the nicest conversation.

It was, you know, about girls.

We're about two or three blocks down now.

Right about this section is where we initially stepped into the street, and I was on the sidewalk the whole time until we got to that point.

(bells ringing hour, children playing) Like I said, we were walking down Canfield.

We made it down two or three blocks before we hit the leasing office.

That's the beginning of the apartments.

And then we stepped into the street.

At that point, there was no traffic.

We didn't see no harm in it.

We was in the middle of the street on the double yellow lines, and now we're walking east towards both our home, 'cause I stay to the right and Mike stays to the left.

But it, it was, like, we're not interrupting anything, no horns were honked, nobody screamed or yelled out their window, "Hey, kids, get out the street."

And we're walking in the middle of the street, I was walking and he was standing behind me walking, we, like, in a straight line, almost, up the street.

So I'm in front and he's directly behind me, we're walking toward, I want to say, it's south towards Northwinds, which is at the back of the Canfield apartments.

Single-file line.

Walking straight on the double yellow lines.

(woman singing faintly) TIFFANY MITCHELL: As I come around the corner, I hear tires squeaking, and as I get closer, I see Michael and the officer, like, wrestling through the window.

Michael was pushing, like, trying to get away from the officer, and the officer was trying to pull him in.

As I see this, I pull out my phone, because it just didn't look right.

You never just see a officer and someone just wrestling through the window.

The officer gets out of his vehicle and he pursues him.

As he's following him, he's shooting at him.

Until he goes all the way down to the ground.

(car horns honking) (people talking in background) (people talking in background, car horns honking) SABRINA WEBB: And it just so happened to be Canfield.

(people talking in background) We lived in Canfield, and it was just simply a phone call.

It was one of my roommates.

And she was hysterical.

She was crying, she was upset, she was scared.

And she said, "I believe I just watched somebody get killed in front of our apartment."

MAN: Let me tell you why this is important.

They got over 20 police dogs in here.

They put them on us because they don't understand that we're grieving.

WOMAN: Yes... WEBB: Not even knowing that it was a relative of mine, I dropped the phone.

MAN: We want you to do exactly what the mother and exactly what the father's wishes are, to support them.

We don't need you burning nothing.

We don't need you to come up with no bright ideas right now.

If you do exactly what we're saying, and you're unified like what we're doing, I promise you we won't have no problems.

- By tomorrow at 10:00, we going back around to Ferguson.

And we want to do it just like this, with our hands up, no violence.

- No violence.

- Just positivity for Mike Mike.

For Mike Mike.

I need y'all with me.

So we got to do it the right way.

WEBB: And I'm standing there and I'm just looking at this guy on the ground, and I'm, like... You know when you realize that you know somebody, but you don't want to accept the fact that this may be the person that you know.

So, when I heard his name, I'm, like, "Nah."

MAN: People came down here to mourn the death of Mike Brown.

PROTESTERS: Put your hands up!

MAN: I want your hands all the way up!

Because this how he was when he got shot.

WOMAN: Yeah.

MAN: When he got assassinated.

WOMAN: Yeah.

MAN: When he got executed.

This how he was.

PROTESTERS (chanting): Enough is enough!

(chanting): No more!

No more!

MAN: Everybody get your hands up, get your hands up!

MAN: Okay, now, we are a peaceful demonstration.

And we letting them know that we are civilized, and we are unified.

And enough is enough!

PROTESTERS (shouting): Enough is enough!

MAN: No justice, no peace!

(lawnmower running) BOYD: Well, there were so many things that happened when you were growing up black.

And if you were to drive around that community during the time when I was a kid, and even as an adult, there was that, um, street that we were talking about that did not run through from Kinloch that should have, you know.

When you look at that barricade, it made you feel that, "They think I'm inferior," you know.

And I don't like that, it makes me uncomfortable, and why should it be?

And then if you were to leave that area, and just drive up Mable Street, where the Vernon School was located, and see how that was segregated.

And then if you were to continue around to Courtney Avenue, which was in the city of Kinloch, but on one side of the street was Kinloch and the other side of the street was Berkeley.

And all along that area, there were fences there.

And it ran along the north boundary of Kinloch.

GUNTHER: I honestly only surmise whether hedgerow was here naturally or if it was intentionally planted.

I do not have personal knowledge of exactly why.

It is here, it is along the fenceline, it is along the border.

I can only guess.

BOYD: Those houses were built so that their backyards were to the city of Kinloch.

And so, the isolation was intentional... And it just, I believe, preyed on people... Who hadn't done anything to deserve it.

NEWSREEL ANNOUNCER: And 5,000 paratroopers reinforce the National Guard, state and city police.

The city's industry and business are severely affected.

(dramatic music playing in film) A besieged city of guerrilla warfare.

Sniper groups use day-and-night hit-and-run tactics, before tanks move in to curb their window and rooftop barrage.

Wreckage is everywhere.

MALCOLM X: No man can speak for Negroes and tell Negroes love their enemy.

No man can speak for Negroes and tell Negroes, "Turn the other cheek."

No man can speak for Negroes and tell Negroes, "Love, suffer peacefully."

There is no Negro in his right mind today who is going to turn the other cheek.

(audience applauding and cheering) MAN: I love it!

MAN: Friday Freedom Flicks.

WOMAN: I can't hear you.

MAN: The whole goal is to...

So we can watch some political films, educate the community, bring everybody together, then have some dialogue about what we watched, what we learned, how we can incorporate it with the stuff that we going through today.

It's just what Hands Up United is all about.

So at this point, I'm going to turn it over to my bro Tef Poe.

TEF POE: Can anybody identify... CHILD: Mommy!

TEF POE: Some of the prime targets from the black liberation movement who was the FBI primarily concerned with taking out, according to the movie?

WOMAN: According to the movie, they was concerned with taking out the Black Panthers.

- Ding, ding, ding, for 500-- if I had prizes... (woman laughing) But I don't.

You got a whole bunch of black folks with guns and educated, giving food back, where literally, we're still living off the WIC program.

WOMAN: Right, that they created.

- And we modeling things off that same program, you know what I'm saying?

Right now today, you know what I'm saying?

So, given that, you know, you always gotta take into context how they don't, you... niggas with guns is a problem, you know what I'm saying?

You don't need niggas with guns teaching people and feeding people at the same time.

WOMAN: Right, because they thinking about... - So you have to take out the Black Panthers.

We do this program in the same spirit in which they did the original Books and Breakfast.

You know what I mean?

And I put it last, because after we get through discussing all of these problems, we got to get to the point where we have some solutions.

This ain't the end-all-be-all, but we feel that this is one of the things that intersects between these kids, and young adults, before the streets get them, before the police get them, before the system get them, we got to get them, so that's what this is about.

(footsteps padding, birds chirping) (crickets chirping) (birds chirping) BOYD: The airport.

It was such a nuisance, and it was really prime location for anybody who wanted to use that property commercially.

And eventually, that is what happened.

The airport buyout came about and so many people moved away.

I guess you've driven through there since most of the houses have been torn down.

It just no longer was a viable community.

JOSEPH SPEARS: Over the years, this became what they call the crash zone for the airport.

GILLOOLY: So that's why they wanted to buy it up?

So they had... CLEA TUCKSON: That's why they did buy it up.

GILLOOLY: Okay.

TUCKSON: Oh, yeah, they own the airport, they own all this, too.

The City of St. Louis owns Kinloch, in a sense.

WILL: That just, that decimated the town, you know?

It just, it killed everything.

And they really didn't use all the land, they just... You know, the population went from, like...

I want to say it was about 10,000 people, all the way to, like, 200 or 300.

And it's never been the same.

JOSEPH WELLS: I was mayor when they first started buying it out.

All the damage was done, you know.

You didn't have nowhere to expand, so you was locked in, and that kills any city.

It don't make no difference who it is or what city it is.

You don't have no extra land and you're locked in all around, Ferguson on one side and Berkeley on three sides, you know.

So Kinloch was doomed from the beginning, but... 25 or 30 years ago, when I was the mayor, they had already designated Kinloch to be cleared out for the airport.

(airplane passing overhead) (airplane passing overhead) BOYD (dramatized): At this point, we could begin the difficult task of restoring each man to a level of human dignity.

Within a generation, all traces of the nightmare could become no more than a matter of history.

Alas, I've been daydreaming.

As I awake from the dream, my heart begins to bleed again, for in my heart, I know that too few will try.

So what do we say to the rioters?

BOYD: You know, if I seem to be dancing around the question, I just don't know how to deal with it any other way.

It's, it's something that I've been affected by all my life, my friends and family members the same, and I think that is what was going on during the time that I worked in the city of Kinloch.

It was with me when I was in school, it's with me now, it's with me as I listen to the politics of what goes on in the United States, and... What are we waiting for?

Why can't we straighten this thing out?

BOYD (dramatized): I don't really know how to end this letter.

I do thank you and the Zion congregation for your hospitality and pray that God may bless you.

Sincerely, Julia Boyd, coordinator.

GIRL (on recording): "Fourscore and seven years ago, "our father brought forth upon this continent a new nation, "conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition "that all men are created equal.

"Now we are engaged "in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, "or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, "can long endure.

"We are met on a great battlefield of that war.

"We have come to dedicate a portion of that field "as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives "that that nation might live.

"It is altogether fitting and proper "that we should do this.

"But in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate, "we cannot consecrate, we cannot hallow this ground.

"The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here "have consecrated it far above our poor power "to add or detract.

"The world will little note nor long remember "what they say here, "but it can never forget what they did here.

"It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here "to the unfinished work which they who brought here "have thus far so nobly advanced.

"It is rather for us to be here dedicated "to the great task remaining before us, "that from these honored dead, we take increased devotion "to that cause for which they gave "the last full measure of devotion, "that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain..." (airplane roaring overhead, drowns out recording) GIRL (on recording): "...Shall not perish from the Earth."

CONRAD SMITH: Kinloch is an all-black politically independent city located in suburban St. Louis County approximately seven miles northwest of St. Louis city limits.

Although the city is surrounded by the predominantly white community of Berkeley and Ferguson, it is sharply separated from it...

PETTY: He built the junior high, that was the city hall.

He built Smith School.

Everything basically was brick around here... BRAWLEY: There were some things that are very controversial, and one of them was a street that had always been closed.

BOYD: One thing that I remember is that we were angry, and today people are angry.

There are a lot of things... (archival): This picture was taken from the Ferguson side, the sign says "Pavement End."

WILLIAMS (present-day): Nobody ever gave us any official information as to why that barricade... (archival): Took the name off of the sign and called the real estate people, but the real estate people wouldn't call us back.

HESBURGH: The United States Commission on Civil Rights is an agency of the United States government.

Its duties are to study and collect information... SQUIRES: We got what we wanted, which was the freedom and ability to go places and buy homes.

But we lost what we had.

AMANDA SMITH: They didn't want us coming over there, but we went anyway.

JOSEPH WELLS: We didn't have nowhere to expand, so you were locked in, Ferguson on one side and Berkeley on three sides.

WILL: My kids, I bathe them in blackness, because once you walk out that door, you're dealing with white supremacy.

In the home, you have to bathe them... WRIGHT: Which neighborhoods are going to be black, which neighborhoods are going to remain white.

WHITT: They're still in denial because they don't encounter the same type of police that we do.

SELTER: We never talked about the hard stuff, and it's the hard stuff that's coming out now.

CARTER: This Brown thing, that stuff's been boiling for years and years and years and years.

GUNTHER: I honestly only surmise whether it was here naturally or if it was intentionally... O'GUIN: With the segregation in the county, we was forced to build houses in Kinloch.

HARRY: I'm heartbroken for the parents of the child that died yesterday, I'm heartbroken for my community, I'm heartbroken for my city.

COOKSON: There was some sort of divide, wasn't there?

DISPATCHER 2: It's going to be a black male in a white T-shirt.

He took a whole box of Swisher cigars.

JOHNSON (dramatized): We was in the middle of the street on the double yellow lines, and now we're walking east towards both our home, 'cause... WEBB: Not even knowing that it was a relative of mine, I dropped the phone.

SPEARS: This became what they called the crash zone for the airport.

TUCKSON: That's why they did buy it up.

The City of St. Louis owns Kinloch, in a sense.

BOYD (dramatized): I bleed too easily, and this is my sickness.

It is better to bleed than to have the sickness of those who inflict the wound.

TEF POE: We feel that this is one of the things that intersects between these kids and young adults, before the streets get them, before the police get them, before the system get them... FANNIE WELLS: It's gonna be a battle, mm-hmm.

♪

Where the Pavement Ends | Promo

Video has Closed Captions

A haunting look at the deep and lasting wounds of segregation and racial injustice. (30s)

Where the Pavement Ends | Trailer

Video has Closed Captions

A haunting look at the deep and lasting wounds of segregation and racial injustice. (1m 36s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipMajor funding provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. Additional funding provided by the Wyncote Foundation, the National Endowment for the...