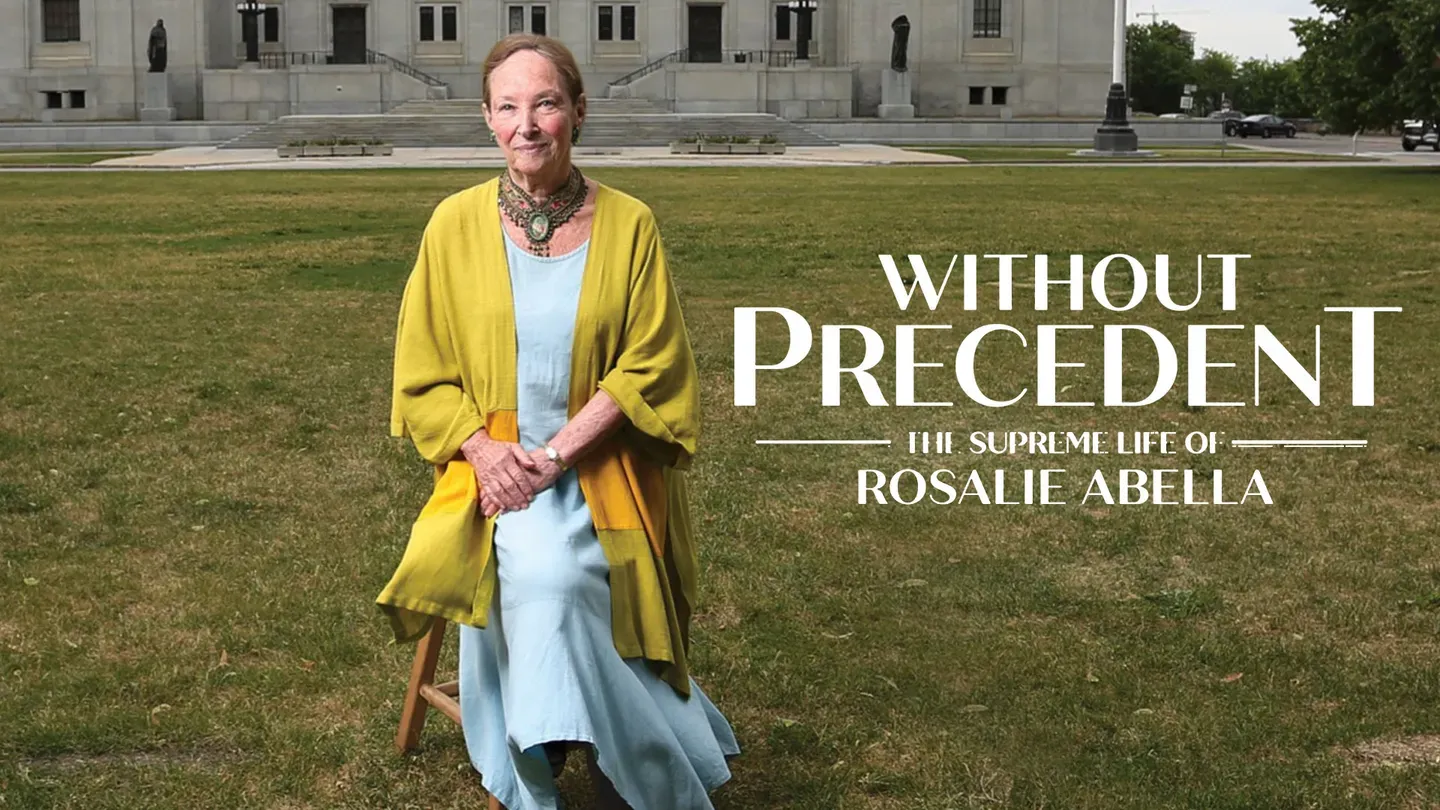

Without Precedent: The Supreme Life of Rosalie Abella

Special | 1h 20m 51sVideo has Closed Captions

The life and career of Rosalie Abella, a former member of the Supreme Court of Canada.

Without Precedent chronicles Abella’s remarkable career advocating for the rights of women, people with disabilities and visible minorities, along with the expected observations about compassion and social policy from talking heads like New Yorker journalist Adam Gopnik, Margaret Atwood and several former Canadian prime ministers.

Without Precedent: The Supreme Life of Rosalie Abella is presented by your local public television station.

Distributed nationally by American Public Television

Without Precedent: The Supreme Life of Rosalie Abella

Special | 1h 20m 51sVideo has Closed Captions

Without Precedent chronicles Abella’s remarkable career advocating for the rights of women, people with disabilities and visible minorities, along with the expected observations about compassion and social policy from talking heads like New Yorker journalist Adam Gopnik, Margaret Atwood and several former Canadian prime ministers.

How to Watch Without Precedent: The Supreme Life of Rosalie Abella

Without Precedent: The Supreme Life of Rosalie Abella is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

[bells tolling] Rosalie Silberman Abella: This is not just the last sitting day of the Supreme Court year.

It is also the last sitting day of my Supreme Court career.

People like me, female, Jewish, immigrant, refugee, weren't exactly being appointed to the bench in droves.

But if somebody wanted to make me a judge, who was I to say no to the opportunity?

After all, immigrants live for opportunities, not entitlements.

♪♪♪ ♪♪♪ Ron Daniels: Who doesn't know Rosie Abella?

Everyone knows Rosie Abella.

♪♪♪ speaker: She was the youngest judge in Canadian history.

speaker: Seventeen years as a Supreme Court judge.

Margaret Marshall: One of the great living justices in the world.

Brian Mulroney: Great sense of humor.

Great sense of history.

Adam Gopnik: Challenging figure in terms of what she stands for as a thinker.

Margaret Atwood: Rosie was the roll-up-your-sleeves person.

Joe Clark: Who was able to move institutions on thinking forward.

speaker: Rosalie Abella leaves the bench, but she leaves a long legacy.

Rosalie: I wrote a gay rights judgment.

Mary Condon: She was really taking very seriously the rights of women, other minorities.

Gerald Chan: Her decisions have had such a wide-ranging impact on Canadian society.

Ysabella Hazan: Very inspiring, influential, definitely iconic.

Jamie Liew: Humanitarian and a compassionate judge.

Andromache Karakatsanis: She's also lectured, spoken, taught round the world.

Paul Martin: Well, there's no doubt about her drive, but she was also a lot of fun.

Charles Bronfman: No other adjective I can say except she's Rosie.

♪♪♪ Rosie: This is the office I've been in for the last few years.

It's an incredible office.

It feels like home to me and I'm so comfortable in here.

These are all things that make me happy and smile.

I always look at my kids.

Every office I've been in, I've made sure that my desk is facing the picture of them when they were 9 and 12.

The Gershwin poster always makes me happy because those are my second-favorite brothers.

This was my father's diploma from the Jagiellonian University that he graduated from in 1934.

He was there from 1930 to 1934.

When we went to Poland, my husband and I went to the Jagiellonian law school and I said to the person who showed us around, "Is there anywhere I could see what he studied?"

What I saw was that his religion was mentioned in three different places, Jewish.

I asked her about the religion and she said, "You know, hats off to your father, it was very hard to be Jewish here in those days.

And so I cried.

Adam Gopnik: The story of how her parents came to Canada, to come out of the background of the Holocaust to become the most revered justice in recent Canadian history, that's an extraordinary story, and it's a kind of only-in-Canada story.

Rosie: In fact, I didn't know my mother had owned a factory in Poland 'cause all she did was talk about my father and how brilliant he was and how he went to university on scholarship and Jews didn't.

Rosie: One of the things that I found, this is from the district judge of Radom, "It is further mentioned that at the order of the president of the Court of Appeal at Lublin as of July 26, 1939, Mr. Silberman was admitted to the examination as a judge in the period 26 to 28 October, 1939."

I never knew that he had applied to become a judge.

But of course, October '39, the war started, and there was no practicing law, never mind becoming a judge.

Rosie: My parents ended up in concentration camps for most of the Second World War.

They had a child, my brother, who was two and a half, who was killed at Treblinka.

My father's whole family was killed at Treblinka.

I kept asking what was it like in the concentration camps?

They never talked about what they had lost, even talking about their son.

They just were not people who complained about what had gone before.

Rosie: So these are the papers that my mother gave me and this was my father when he was head of the Displaced Persons Camp in Southwest Germany where they went after the war and where I was born.

Zachary Abella: You would never know by going into her household, the horrors that she would have heard growing up in her house with her survivor parents and her survivor grandmother.

Rosie: Of all the houses I went into as a child growing up, mine was the happiest.

They were the happiest people I knew.

I felt I was floating through childhood.

Bernie Farber: I honestly think it's her immigrant experience, being born in Europe postwar, coming to a country that welcomed her on one hand but didn't allow her parents to accomplish what they wanted to accomplish.

♪♪♪ Rosie: This was from the Law Society of Upper Canada where he went in order to see if he could practice law in Canada, and they said no.

But I wanna show you that there are letters here from lawyers and judges he worked with in Germany that just recommended him for jobs in Canada.

He just assumed he was gonna practice.

Rosie: My decision about being a lawyer was only because I heard at the age of four that the Law Society had told my father he couldn't be a lawyer because he wasn't a citizen.

So when I said, "If you can't do that, I'm gonna do that."

I had no idea what I was talking about.

Rosie: I remember my father saying, "Don't worry about being popular.

The most important thing is for people to respect you."

And so I grew up thinking I do want that and I worked even in public school, in high school.

But I also didn't mind being popular.

I'm a girl.

What can I say except that that mattered too.

Rosie: And one night when I was about 11 or 12, I was in the basement with my grandmother watching her prepare for the Passover Seder, and they said, "Don't you do the housework, we'll do it.

Go do your homework."

It wasn't until I read "Les Misérables" when I was 12 or 13 that I connected what I wanted to do with what justice is because of the gross injustice in that book.

So I went from being a child who just, by rote, said, "I wanna be a lawyer," which people patted me on the head for and pinched my cheeks at weddings and bar mitzvahs, "Isn't she cute?

She wants to be a lawyer," to actually wanting to be a lawyer.

Rosie: My parents talked to me like an adult and they also left a very strong sense in me that I had a responsibility to pay Canada back, that we'd been given a gift of being able to come here and I had to repay that gift by being somebody Canada would one day be proud of.

♪♪♪ ♪♪♪ Rosie: I got to law school where there were a lot of rules and a lot of cases to read, not all of them very interesting, and I thought, "God, I hope I'm doing the right thing because this doesn't seem to be helping anybody," but those are the tools of the trade that you have to know how to do.

♪ Holding hands at midnight.

♪ ♪ 'Neath the starry sky.

♪ ♪ Nice work if you can get it.

♪ ♪ And you can get it if you try.

♪♪ Rosie: I remember the call to the bar in 1972 because there were 520 people at the O'Keefe Centre, 14, 15 women, and I thought, "Oh, wow.

This is gonna be different," because I never felt like a minority in my life.

But this was the beginning of real life.

So I wasn't scared but I wasn't sure what was waiting for me.

So I continued being who I was from the minute I graduated from law school and met a client.

Like, it's all a sense of responsibility.

You're not there for you anymore.

Rosie: So the one thing I realized when I hit the legal profession was that there were a lot of people in it whose fathers or grandfathers had been lawyers, who came from very successful families, and who kind of expected that they would go to law school and be lawyers, that they would go to the best firms, that they would be judges.

Immigrants don't feel that.

Immigrants never feel that they're entitled to anything.

If you thought you wanted to do something, you had to invest the time, you had to make the effort, you had to probably be better than anybody else, and then if you were lucky, it would happen.

♪ Nice work if you can get it.

♪ ♪ And you can get it if you try.

♪♪ Rosie: Most of my friends from law school went into big firms--big, big firms.

Almost nobody went into a firm of one lawyer, who was a wonderful man, Vince Kelly.

He did labor law, he did criminal, civil, so I did everything.

After two years with him, I wanted to be on my own.

I wanted to control what clients I was gonna take, what clients I wasn't gonna take.

I didn't care about the money.

♪ Nice work, nice work.

♪♪ Rosie: I had my own firm, one lawyer, just me, at the corner of Bay and Queen, and I loved it.

I would have done that forever, practiced law.

It was exhilarating to be downtown, walking to the courts for a client, settle cases in those days and the profession was really wonderful.

speaker: Rosalie Abella, a lawyer, I'd like to ask you, what about the matrimonial home?

Rosie: It's a system of separate property, and separate property essentially means that whoever paid for it and acquired it and in whoever's name that property is registered owns the property.

Rosie: The education started with clients who were telling me things that were very different realities from what I had learned in law school from the cases.

So they were my introduction to what life was like for most women, in particular, no child care, underpaid jobs, the grind of working as a spouse but not being able to get a share of the property if there was a divorce because you didn't contribute financially but, of course, you couldn't 'cause you didn't have a job.

Rosie: Those four years of practice introduced me to realities that were very different from what I'd heard about at law school or from what I'd experienced.

♪♪♪ ♪ Mmm, ♪ ♪ I've got a crush on someone.

♪ ♪ Guess who.

♪♪ Irving Abella: I was a PhD student.

I had just come back from Berkeley and here was a second-year university college student who kept following me.

No matter where I went, there was Rosie.

I had a carrel, a desk, in the second floor of the library at the University of Toronto, and they were reserved, and so I would go down there, sit every day, and behind me there was Rosie.

Rosie: Sometimes doing my own work but, mostly, just waiting for him so I could talk to him, ask him out for coffee.

Irving: And she would wait until I went home and said, "Can I drive you somewhere?"

Rosie: So I came home and I said to my parents, "I met the guy I'm gonna marry."

Now it took him three years to agree with me that that was a mutual proposition, but I never stopped feeling that this was the man I wanted to spend my life with.

♪ But you had such persistence.

♪ ♪ You wore down my resistance.

♪ ♪ I fell-- ♪♪ Irving: That was our relationship for-- Rosie: Fifty years.

Irving: For at least three years, and then I fell in love with her.

Rosie: After we were married?

Irving: Soon after.

Rosie: Soon after.

♪ You were my big and brave and handsome Romeo.

♪ ♪ How I won you I shall never, never know.

♪ ♪ I've got a crush on you.

♪ ♪ Sweetie pie.

♪♪ Rosie: The idea that he would be somebody who would welcome having a wife who was gonna have a career, and I was, and who turned out to be the most remarkable father to our two sons, none of that is predictable.

I'm in awe of everything about him.

But mostly what I'm in awe of is that I got him.

I never gave up.

People kept staring at what I was doing and saying, "How can you--he's not interested."

I know.

It's fine.

I am.

I'm interested enough for both of us.

♪ The world will pardon my mush.

♪♪ Zachary: They are completely sympatico.

They know each other better than any two people could know each other.

Jacob Abella: It's hard to explain the synergy, how they fed off each other.

Like, he leaned in before anyone else did.

Rosie: In our house, he is a man who knows how to navigate so that every single member of the family has their turn.

And he's willing to put himself second in order for each of our kids as they needed.

Charles Bronfman: They are quite a couple, and it is and was a balancing act, always.

Zachary: They knew that my mom is a lot more front and center and broadway, and my dad hung back in his way, was quieter.

Brian: I mean, Neil always used to say about Rosie, "Brian, look, what do you want?

Here, she's a great wife, she's a great mother, she's a great jurist, and she plays the piano like a concert pianist.

What else do you want?"

♪♪♪ ♪♪♪ Rosie: And he guides me.

I trust his judgment.

He's the only one I always go to for advice.

The only one.

And he's never wrong.

I told you that before.

He's never wrong.

Irving: You're the one who's wrong.

Rosie: I know, but I wasn't wrong in picking you.

That was really smart.

♪♪♪ ♪♪♪ Rosie: Life changes because I get a phone call from the chief judge of the Family Court.

Jim Reed: Family Court, the place where tears run freely and authorities make Kleenex available everywhere.

Emotions run high.

This is the place where families finally break down, custody goes to one parent or the other, and children must face up to their crimes.

Rosie: I was seven months pregnant with our second son.

Remember Roy McMurtry who was then the attorney general whose decision it was, and I'm meeting him in the afternoon and he looked down at my stomach and he said, "When did that happen?"

I said, "Seven months ago."

He said, "Well, it's too late.

I've put your name before cabinet.

It's going on Monday."

They were looking for women judges, and there weren't any on the Family Court.

And so, I called my husband.

He wasn't sure.

He told me how much I'd earned that year.

I had no idea.

And I was going to be taking about a fifth, but it didn't matter.

I thought it was a challenge I couldn't resist.

Jim: Tonight, we look at one of the new breed of judges, Rosie Silberman Abella, who, when she was appointed to the bench, was the youngest woman in that job.

Rosie: But the Family Court taught me a different level of despair, because the people who went to the Family Court for their family problems were the people who usually could not afford a lawyer.

And they were the people who couldn't get a sense of ownership in society because they had no access into it.

They really were struggling with their children, struggling with their spouses, struggling with poverty.

I mean, I learned to listen as a Family Court judge.

I learned you don't look at these cases from the top down, from what your life is like, what your kids are like.

What are they telling you are the barriers to their being able to get through their parenting, their spousal relationships?

Sometimes, I heard 20, 30 cases a day.

Making decisions about their children, their lives, their survival economically that wasn't gonna do harm, if possible.

♪♪♪ Rosie: That's where I learned that law isn't just about rules.

Justice is about the application of the rules to life.

Is it wise?

Not how smart you are as a judge.

Are you wise as a judge?

That was an intense year where I learned about a whole other range of vulnerability and disadvantage that I had not been exposed to, either in law school or in life.

And that changed me.

So everything I've done that exposed me to something different from what I've known, made it easier for me, as it turned out, to do the next thing.

♪♪♪ Rosie: I did not know if this was gonna work, having children and a career and I'm a workaholic.

So I figured out early on, I came home every day for dinner, and then I went back downtown to finish my work every night after the kids were in bed.

speaker: Abella home videotape.

Tell me about the Abella mystique.

Irving: The Abellas have never made a mistake in their lives.

It's part of the Abella mystique, not to make mistakes.

So there is no Abella mistake, and the only mistake we had was in buying somebody a camera.

Zachary: She was home as much as possible.

I used to joke because it was an easy laugh line that she wasn't home that often, but the truth is she was.

Jacob: It is extraordinary because I try and think of that, you know, as I entered parenthood and as I, you know, tried to juggle work and one kid, how she was able to do everything she did and still make both my brother and I feel like we were, quite literally, the center of the universe.

Zachary: And people usually have difficulty believing that we could have had such a "normal" home-life, but we did and that was by design.

They didn't want us to have any, really, external pressures beyond, you know, just growing up in Toronto and being successful.

♪♪♪ Jacob: Would you please go away 'cause, like, I have work to do, please.

Jacob: My mother was a very wonderful and present mother, despite having a career.

But my father, he really stepped up.

I mean, he played such an incredible and important role in raising us.

Rosie: He never said, "Just a second, I have to finish this book," ever.

He was 100% available to all of us, to all three of us.

Irving: As an academic, I could do that while Rosie was out doing what she had to do, and then when I was busy, she would take over and so it's a mixture of foreground and background for the two of us.

Jacob: The way she was able to do it in a way that we never felt neglected, that she was always present, and she made extraordinary sacrifices for that, you know?

People look at her career and think, "Well, you know, it's just a continuous trajectory."

It's not.

She turned things down so that she could be with us.

She would, actually, not go to things that could have been important for her career, so she could just have dinner with us.

Rosie: And I kept my fingers crossed that they would be nice people and that they would be happy people and that I wasn't a barrier to their self-fulfillment.

Zachary: They wanted us to be kids and they wanted us to be young adults in that household and they didn't want us to be the son of the president of Canadian Jewish Congress and the son of a judge.

They just wanted us to be normal kids and, to their great credit, we were.

Jacob: There was never any sense, "Thou shalt--you must go forth and make the world a better place."

I would say it was an expectation that underlay everything.

It came out pretty much all the time and you didn't think about it because that's who they wanted us to be, and that's who they were, and that has forever driven me.

Rosie: I can say it.

They are wonderful people and they've got wonderful families of their own.

♪♪♪ ♪♪♪ speaker: A Royal Commission report told the federal government it had to increase employment opportunities for women and for minorities.

Today, the government said it will.

Charlotte Baigent: In the 1980s she wrote the equality report on "Equality in Employment."

speaker: Here's an indication of how sensitive the issue is.

Judge Abella rejects the term "affirmative action."

She prefers "employment equity."

Rosie: We didn't have a definition of equality in this country until the Royal Commission report.

And I had to figure out what equality meant.

We had not yet decided it.

Brian: Canada was, in many ways, pretty neanderthal, and Rosie appeared determined to cause us to break out of this.

Rosie: If, in this ongoing process, we are not always sure what equality means, most of us have a good understanding of what is fair, and what is happening today in Canada to women, native people, disabled persons, and many racial and ethnic minorities is not fair.

Rosie: That was a one-year, $1 million study into those four groups, 60% of the population.

And I had to figure out what equality meant.

Mary Condon: She has, sort of, understood the particularities of women's experience both with respect to the work world but also caregiving and other kinds of family obligations.

Martha Minow: Take the example of parental leave.

You could treat men and women the same by saying no one gets parenting leave, but she says, "No, there's a reason why parenting leave is a special issue for women, more than men, it has to do with society and how society has structured the parenting role.

And therefore, the equality solution has to be everybody gets parenting leave."

Rosie: Which is why, of course, I ended up deciding that if we're gonna define equality in this country, it's not about a level playing field because there isn't one.

Rosie: And so I came up with the idea that you have to think of equality as acknowledging and accommodating people's differences so they can be treated as equals.

♪♪♪ Rosie: You don't build a ramp for somebody who's in a wheelchair if they're not gonna be able to get access.

But if you treat them like everybody else, treat them the same as an able-bodied person, they don't get a ramp.

So I think we figured out equality in this country better than any other country.

Charlotte: Concepts like substantive equality and systemic discrimination came from that report.

Zachary: I remember at the time how controversial it was and the terrible things that people were saying about it.

Carole Wallace: I have been reading the report, rather than listening to Judge Abella, and my conclusion is this Royal Commission was a scandalous waste of taxpayers's money.

Brian: This was quite a--an advanced theory at the time.

She met resistance in caucus and in cabinet.

Lorne Nystrom: Where are the goals in this-- in her statement for employment equity?

Where are the targets in her statement for employment equity?

Now where is the timetable in terms of imposing employment equity in the country--in this country of Canada?

Rosie: Universally, all of my "protectors" said, "Don't do this.

This is really controversial."

"Really?

Controversial, difficult, complicated?

I'll do it."

And so I did, and it was a disastrous reception that I got.

Geoffrey Hale: The entire analysis that Judge Abella has taken has been appallingly one-sided.

Rosie: Every newspaper in the country from one end of the country to the other said, "This is terrible.

This is reverse discrimination."

And I used to say, "No, it's not reverse discrimination, it's reversing discrimination."

Martha: Just absolutely spectacular report that transformed the thinking about how equality is treated in the law.

Rosie: The requirement that we are recommending be imposed on federally regulated employers is that they examine their workplace practices and take steps to eliminate those barriers which disproportionately and negatively affect members of the four groups.

Rosie: If we'd had a merit system all along, a lot of these people that had been excluded would have been there in the first place.

Brian: I was very impressed at what she had done and so I called in Flora MacDonald who was employment minister at the time and told Flora I thought we should get this done.

Flora MacDonald: There's no question that the case for equality has been made, certainly by Judge Abella, and it's certainly accepted by this government.

Zachary: A Conservative government in Canada adopted that.

That doesn't happen very often.

Brian: This is not a partisan issue.

Fairness for women is something that is good for all.

Joe Clark: She is a very appropriate expression of what equality means.

She doesn't only fight for it, she represents what, at its best, it can be.

Charlotte: And it's influenced equality law all over the world.

Rosie: But am I proud of the role I played in equality rights in this country?

Oh yes.

Zachary: You could make a legitimate argument that for at least a couple of decades there was an open question on who was more well known than the other.

In certain neighborhoods in Toronto, he was certainly more high profile than she was.

♪♪♪ speaker: Today, we'll chat with Professor Irving Abella, the co-author of the recent bestseller, "None is Too Many."

Rosie: Canada, as you know from "None is Too Many," was not allowing in Jews until 1948.

Irving: This was the most difficult book that I ever did.

There were times when we sat in the archive, almost crying in frustration.

On the other hand, we felt that we had an entire generation of people looking over our shoulders as we were writing.

We had their story to tell.

Rosie: I'm in awe of his dignified, courageous stoicism, which is wrapped in the best brain I've ever met.

I don't write a letter or a speech that I don't run the ideas past him.

When I have a case, I will discuss it with him often, especially if I'm about to do something that I know is gonna get me into trouble.

And he will almost always weigh in on the side of creative pragmatism.

I was at a drugstore and I said, "I'm here to pick up the medication for Irving Abella," and a woman who must have been about 60 years old came up to me and said, "The Irving Abella?"

And I said, "I--who do you--yeah, I think so."

And she said, "The man who wrote the book.

My mother has a book.

Oh, my God, he is amazing.

You know him?"

I said, "Yes, I'm his wife."

"Wow, well, tell him I think he's great."

And I'm thinking, "She hasn't got a clue who I am."

Rosie: Itchy, how are you feeling?

Irving: Great.

I like the part about me especially.

Rosie: See?

speaker: Live from Ottawa, "Encounter 88."

An exchange of views by the leaders of Canada's three major political parties on the issues of the federal election.

Rosie: Tonight, the leaders of Canada's three political parties will have an opportunity to confront one another, exchange views, and share their vision with you.

Rosie: Why did they pick me?

Probably for the same reason I got picked for a lot of things in the '70s and '80s, we've never had a woman yet, and they always knew if they called me to do something, I would always say yes.

Brian: This is not an easy thing to handle Turner, Mulroney, and Broadbent in a major debate that was gonna shape the future of Canada.

Rosie: And I couldn't walk.

My knees were shaking.

Rosie: The participants have agreed that the moderator can intervene where appropriate to enforce the rules as fairly as possible.

I know there are a lot of caveats in that explanation, but I think you can't expect anything else from a moderator who's a lawyer.

Rosie: But what I do remember was having to cut off Brian Mulroney, the prime minister at the time.

Brian: It's something to be proud of, and you should not involve married women-- Rosie: Mr. Mulroney, I'm-- Brian: With a question of patronage.

Rosie: Sorry to interrupt, Mr. Mulroney.

It would be a lot easier if we could hear one of you at a time.

Rosie: And then I let them go during the free trade debate.

This was something the whole country was watching.

[John Turner and Ed Broadbent both talking] Rosie: Gentlemen, excuse me, gentlemen.

It's not fair to either position.

Gentlemen, I'm gonna ask you, please.

We can't hear either one of you when you're both-- Rosie: And I called my mother and I said, "How did it go?"

And she said, "You cut off the prime minister."

Brian: And I think the federal-- I think the criminal court-- Rosie: Mr. Mulroney, thank you, Mr. Mulroney.

Mr. Mulroney, I'm gonna ask you to wind up now please so I can give Mr. Broadbent an opportunity to reply.

Brian: I'm sorry.

Rosie: And I remember being heart sick that my mother was worried about what was gonna happen to me because I cut off the prime minister in a debate.

Brian: I thought she did it with aplomb and certainty and good humor.

And I kept my eye on her.

Rosie: 1992, Brian Mulroney appointed me to the Court of Appeal.

♪♪♪ Rosie: And I admired that because the Court of Appeal was the most distinguished court in the country.

Brian: As you know, all appointments to the Courts of Appeal are made directly by the prime minister.

So when it came time to elevate Rosie to the Court of Appeal, I was convinced that she was the best person for the job.

And that was it.

Rosie went to the Court of Appeal.

♪♪♪ Jacob: My mother was of a different world and she was pro human rights person, she was a pro equality person.

She believed in inclusion.

She believed in equality of opportunity.

And yes, there was a lot of criticism.

Brian: There are a lot of smug Canadians who say, "We're a gentle, thoughtful, generous people."

Not always.

You know, there are--we've got our own bunch of morons in the country, and they surface at times like this.

And when Rosie was appointed, I got a lot of correspondence about it from some of the haters, you know?

And they didn't like the idea.

They didn't like her ideological bent, they didn't like her career, and they didn't like the fact that she was a woman, and they didn't like the fact that she was Jewish.

Irving: I'll tell you how bad it was.

Our son, Zachary, would get up in the morning when the papers were delivered, before Rosie got up, and he would go through them quickly to see if anybody had anything to say about his mother that was unfair and critical and remove them so that when Rosie read the paper, there were articles missing.

Zachary: She is brilliant and people know that now and they knew that then, but there were people who, I guess, for whatever reason, wanted to act like this intellectual heavyweight was a social climber.

And that hurt all of us, 'cause it wasn't true.

Brian: It was more ideological.

You know, "Look, we're a Conservative government, Prime Minister.

What are we doing appointing a notorious leftist to an important position in the Canadian judiciary?"

And I said, "Well, she doesn't look like a leftist to me.

She looks like a talented young woman who's made a career in the law and I know her for her good judgment and her good humor.

And what the hell more do you want from a judge?"

Ron Daniels: She demonstrated a capacity to deal with difficult legal issues, to be able to write decisions which earned the support of her colleagues on the court.

Rosie: I just never, never thought about writing letters or criticizing people publicly.

To this day I haven't because those reviews, they were entitled to have.

[cheering] Christopher Beaucage: I knew that she had written the unanimous court decision in Rosenberg that allowed same-sex couple to be able to give their pensions to their spouse.

♪♪♪ Rosie: When I wrote a decision in a case called Rosenberg, which said that the provisions of the Income Tax Act which only allowed you to leave pension benefits to opposite-sex spouses, I wrote the decision and read in the words "or same sex."

Michael Leshner: We got pension rights recognized as a couple.

It was everything for us.

Mary: This is another way in which human rights need to be validated and to be advanced, the way in which law should recognize the equality of people based on their sexuality.

Rosie: And that's what judges can do in the protection of rights.

They can take chances with public opinion.

In fact, they are obliged to take chances with public opinion if they think that's the right way to go, constitutionally.

Now, are there people who felt differently?

Yes, of course.

But there's only one way to measure whether that decision was right, and that was time.

♪♪♪ speaker: To Ottawa now and the death of a man the prime minister described today as one of the finest jurists in the country.

Supreme Court Justice John Sopinka died suddenly this morning after a short illness.

He was 64 years old.

Rosie: John Sopinka died, and suddenly there was a vacancy no one had expected on the Supreme Court of Canada.

And the candidacies were expected to be Court of Appeal judges.

I mean, that was the natural farm team for appointments from Ontario to the Supreme Court of Canada.

I would say it was a period of hyper activity on the part of people who were promoting particular candidates for the Supreme Court.

And it was an awkward time.

And I was somebody whose name was out there, and I was a lawyer and a judge who was shifting borders.

All the legal boundaries in so many areas were changing, but when you change boundaries, you change expectations, and when you change expectations, some people are happy because they've now been included, and some people are unhappy because more people have been included in something they thought they were exclusively entitled to.

So, being known as somebody who changed boundaries was not an application form for a promotion to the Supreme Court of Canada.

Rosie: What I read in the press was, "She doesn't have a chance.

She's too controversial."

Zachary: There were stuff that was said about her that simply was not true or fair.

Jacob: Here she was being mooted for something that she was not seeking.

And suddenly, people were attacking her for it.

Zachary: They thought that she had friends in the right circles, she was very social, but she'd lack maybe the intellectual rigor to be on the Supreme Court.

Rosie: Was only painful, I guess, when it was public, when it hit the press.

But again, what can you say?

It's fair to say that I was one of the first people to call Ian Binnie, who was an outstanding lawyer and judge, and highly qualified.

And I was fearlessly doing all of the things that I'd done in my whole legal career because it never even occurred to me to be careful and monitor my activities in a way that would tailor them to the possibility of going to the Supreme Court.

♪♪♪ Margaret Atwood: So, she's a collector of very bright peculiar objects.

Very unusual, both in wardrobe choices and in accoutrements.

Rosie: We're in the living room of the house we've occupied since we bought it in 1971, and all of these things that we've collected, we used to buy each other art.

So what you see on the walls are part of our anniversary presents.

Bernie: And if anybody's been into their home, you'll know you walk into, like, an Alice in Wonderland place.

Jacob: It is a reflection of my mother's personality.

She likes things that make her happy and the collection of art and the colors make her happy.

Rosie: I don't think you would say that there is a style of art.

But it's all sculptures, paintings, artifacts, that are fun, that are creative, in a very different way.

Charlotte Gray: You know, she has pop tastes and some of the pieces that she has actually are quite lovely but you'd never know it, given the junk they're surrounded by.

Jacob: A Fedex person once asked if this house was a store, so, but people loved it.

Bernie: But I had such a blast in that home, I really did.

She knows pretty well every Broadway song that I know, but she sings it much better than I do.

Rosie: Right now, there is no music in the room because you made me turn it off.

But there is always music in a room because my brain looks for it.

Margaret: She loves a party, she loves musical comedies, so, lights, camera, action, that would be Rosie.

Rosie: When I finished high school, as a gift, my parents let me go to New York with a girlfriend and we got tickets to "Funny Girl" because I knew all the songs.

And they were funny songs and they were romantic songs, so I became a fan.

That was food for me, having music in my head to get me through life.

♪♪♪ Irving: So we've never had a really enjoyable meal at home that hasn't been ordered in, and Rosie and-- Rosie: [laughing] I'm sorry.

Margaret: Not a tippity-top cook.

She once took a gourmet cooking class and her family complained.

Rosie: Look at these homemade pastries that I got at a neighborhood bakery.

They're homemade, but not by me.

Rosie: Cooking, I tried because my family needed to eat.

Irving: Yeah, if cooking figured in the family, I would have been gone in the first day.

Rosie tried to make a cheese omelet without eggs.

Nobody told her you needed eggs in a cheese omelet, so she put the cheese in and waited for the omelet to form.

Margaret: Can't we have pizza?

Irving: So we have more recipe books in this house than we've ever had meals.

Sometimes I feel like eating the recipe book.

♪♪♪ ♪♪♪ ♪♪♪ Paul Martin: The Supreme Court reflects in the supreme way what the laws are, but the interpretation of those laws has a very important basis in what your perspectives are that society needs.

Andromache Karakatsanis: We are the court of last resort, so we hear appeals from all courts in Canada and try to bring some clarity and resolve legal issues that have huge impact on every aspect of life.

Paul: When you're dealing with the Supreme Court, what you are looking for is somebody who is a respected jurist, somebody who understands the importance of the law, somebody who understands the importance of the way in which laws are introduced.

I would expect that very much out of somebody who is appointed to the bench.

Rosie: The process that was in place then was you didn't know if your name was even in play.

All I knew was what the press said.

I had no contact with anybody in government from the minute the vacancies started.

Irwin Cotler: Bonjour.

I am pleased to share with you what I would regard as a historic moment.

Rosie: So, people like me never say, "One day I wanna be a Supreme Court judge or a Court of Appeal judge," because we know that we aren't the kind of people who can automatically pick up a phone and think that that's gonna happen.

So if it doesn't happen, that's closer to the narrative that we grow up feeling.

Irwin: I am delighted to announce two outstanding nominees to the Supreme Court of Canada: Justice Rosie Abella.

Paul: Irwin Cotler was the one that came to me and he said, "This is what I would like to do."

Now, Irwin Cotler was universally respected across the country.

And when he recommended Rosie, obviously that gave it a lot of weight.

speaker: But while legal scholars are gushing over the nominees, social conservatives are cringing, particularly with the Supreme Court set to hear a controversial reference on same-sex marriage this fall.

Gwendolyn Landolt: Both of the woman are known as hardline feminists.

It certainly seals the fate of the same-sex marriage case.

Adam: The easiest way to carry on a debate is to invent a straw man, the fake stick picture of what your opponent believes, and then set it on fire and say, "How can you possibly believe such a thing?"

Vic Toews: Paul Martin was looking for a certain kind of a judge in order to advance his agenda.

Rosie: The journalists were very critical of this possibility.

That took me aback, because I'd never seen it before.

And to this day, I don't think I've ever seen a critical reaction to an appointment to the Supreme Court of Canada except mine.

Margaret Marshall: One of the things that I admire about Justice Abella is that she understands that if you are a judge in a democracy, you will be criticized.

Brian: So I wasn't surprised when I saw some of it.

I called her, told her to hang in there, that, you know, this too shall pass.

Rosie: But I can't tell you that it didn't hurt, but I can also tell you that it didn't keep me down.

speaker: This is CBC News.

Today, the Supreme Court of Canada is back in session and it's already completed its first order of business.

Justices Louise Charron and Rosalie Abella were formally sworn in this morning.

Rosie: Do solemnly and sincerely promise and swear that I will duly and faithfully, and to the best of my skill and knowledge, execute the powers and trusts--excuse me, as one of the judges of the Supreme Court of Canada, so help me, God.

Ron: For me, as for so many other legal academics in Canada, when you heard Rosie's name, there was almost an immediate sense of the rightness that Rosie Abella should be on the Supreme Court of Canada.

Brian: When Paul Martin came in, who is a great friend of mine, and ideologically, compatible with me and with Rosie, I was delighted when he appointed her.

Paul: We appointed somebody of substance who was basically gonna drive to very strong social objectives.

Bernie: The message of Rosie Abella being named as the first female Jewish judge in this country was liberating for Jews.

I mean, it was like, holy mackerel, we kind of, "Now we've made it."

Rosie: One born a year after I started practicing law, a journey that started in a Displaced Persons Camp in Germany, ended in the Supreme Court of Canada.

Paul: I believe asking, "Why did you appoint a woman?

Was there something behind that?"

That had nothing to do with it.

We appointed Rosie Abella.

speaker: Tomorrow, the Supreme Court of Canada considers something this country has grappled with for months, same-sex marriage.

Rosie: I wrote a gay rights judgment.

That was the first decision I wrote after all of that criticism.

I wasn't gonna change in order to be able to accommodate those views, 'cause they weren't mine.

Kathy Greenberg: Well, maybe it wasn't the views that they wanted.

Everybody has a right to their own opinion, and she has a certain point of view.

I am assuming that they're--were people that were critical of her decisions.

Michael: You know, there were efforts by people who were opposed to us to say, "Well, you can have something short of marriage."

Rosie: Is it your position that the definition of marriage cannot be changed?

Robert Leurer: That is the position of Alberta, M'lady, within the natural limits of that term.

Rosie: What does--and tell me what you mean by natural limits.

Rosie: I knew it was gonna be controversial.

It was a decision that struck down as unconstitutional on the grounds that it violated protection for--on sexual orientation.

But it got played in the press almost more than the criticism I got for writing the Royal Commission report and saying there should be something called employment equity.

It was really raw in the public's mind.

But that was fine because I'm independent.

I'm not gonna lose my job because I write a decision that protects minority interests.

That's what I'm there for.

speaker: They have been waiting for years to walk down the aisle, gay and lesbian couples in our city, fighting for the right to legally marry.

Today, they won that right.

Michael Stark: Michael felt it was very important that at least one couple get married right after the decision came out.

If you're a member of a group that doesn't have equality, you approach it, obviously, differently because you bring your own experience.

Michael Leshner: Rosalie Abella, everything she's done on the bench, it's really remarkable.

Rosie: You as a judge have to be open to the reality in front of you and not to judge from the top down.

Because their story may not be your story.

♪♪♪ ♪♪♪ Joe: She saw that she had a broad social responsibility as well as that of a member of the Supreme Court.

Mary: She took a particular path and it had a particular voice, I think, with respect to how quickly the law should evolve to reflect a society which was attempting to really make good on its commitments around social and economic equality.

♪♪♪ Kathy: She's unapologetic in the fact that she is not afraid to make laws or reverse laws.

Rosie: The criticisms people sometimes attach to courts is, "You're not really taking into account public opinion.

This isn't what the majority wants."

To which I say, "Public opinion isn't a piece of evidence you can cross-examine and test for the truth, but that's our job: to risk being unpopular in order to do the right thing."

Rosie: Since I first became a judge, I never ever didn't feel that something really important was happening in my court room.

All of the cases felt important to me.

♪♪♪ ♪♪♪ ♪♪♪ Rosie: It was a dispute about whether or not the Immigration and Refugee Board had taken into sufficient account the fact that what we were dealing with was a young person.

Jeyakannan Kanthasamy: I submitted a refugee claim, and then I got rejected.

And they simply said I can go back because the war is over.

speaker: You're not here with status, you're not entitled to be here, you have to leave.

Rosie: You understand what unusual hardship means or disproportionate hardship means or undeserved hardship means compared to hardship, and what I think is difficult to figure out is what role then is there for the words humanitarian and compassionate.

Jamie Liew: Think about, you know, one key case called Kanthasamy where she's taken in her own lived experience as a migrant and has used a compassionate tone, and really is a model in the way in which we can see decision makers take that compassionate and humanitarian approach to decision making.

Jeyakannan: I was so upset, I couldn't even sleep at night, because I was thinking too much.

You know, what if I go back?

What is gonna happen to me?

I was so worried.

Rosie: It was a dispute about the exercise of discretion in applying rules to people who were trying to come to Canada, and making sure that any error was on the side of humanity and compassion.

speaker: Many members of the province's Hutterite community believe that being photographed is against God's will.

Rosie: And that was a case where I thought freedom of religion, their right to exercise their religion outweighed any benefit to the public of having this rule that required photographs.

Rosie: Are we in danger of mixing up the concepts of jurisdiction and justiciability, because when I look at the application for judicial review, there's no mention of religion, there's no mention of doctrine, so the first question it seems to me is, is there jurisdiction?

speaker: An important victory for Labor at the Supreme Court of Canada today.

The High Court struck down a Saskatchewan law that prevented almost all of its public sector workers from going on strike, saying it's unconstitutional.

Rosie: I said you cannot have the protection of collective bargaining which our court had done a few years earlier without the ultimate sanction that goes with collective bargaining, because if you were unsuccessful at collective bargaining, the employer can lock you out, but the only remedy that a union has is to strike.

And no one had ever constitutionally protected the right to strike.

speaker: A landmark Supreme Court hearing began today on whether to allow doctor-assisted suicide.

Rosie: This was a case where it really was a deliberative process.

It was the court, I thought, at its best.

Because it touches on such visceral and personal concerns, we took it very seriously, that it wasn't a crime to assist someone who did not wanna continue to live with intolerable suffering.

Rosie: Why would you be urging us to take an approach that makes it harder, rather than easier, to perform?

speaker: It ought to be difficult.

Rosie: It engaged genuine concerns to make sure that there was no abuse.

I mean, is this going to be used for cavalier purposes or were we really going to be able to protect the dignity of people who had decided the suffering was intolerable?

Rosie: I see justice as the aspirational application of the law to life.

And that means they have a relationship that has to be symbiotic, otherwise it doesn't make any sense.

Joe: I've seen some comment with regard to Rosie as having been too far ahead of her time.

Law has to change.

If law doesn't change, societies lose their own guidance, lose their own cohesion.

And they need change-makers who understand the law as well as they can intuit the direction of the society.

Adam: And so she sees the role of the judge as being in very real ways the advocate for those people, the people who are left out of the underprivileged, or the unrepresented.

Martha: They're called law schools.

They're not called justice schools.

Rosie Abella is someone who narrows, if doesn't eliminate that gap.

Everything that she does is about where's the justice?

Rosie: Why shouldn't the law operate in a way that makes equally accessible to those who are physically as well as those who are not physically able to get the benefit of a more compassionate approach to suicide?

Adam: But I think there was certainly--was and is now a sense that she represents a particularly provocative view of the role of a judge.

She's not modest about the role that a judge ought to have.

Rosie: You know, I remember when there was all this talk and were saying, "We don't want judges with an agenda.

We want judges who are not biased."

And I thought, "Really?"

Then, nobody over 10 years old doesn't have opinions.

Being a judge means knowing you have them and being open to what you hear so that you can transcend your biases which you must confront and be open to the possibility that your instincts were wrong.

Gerald Chan: She's always looking beyond that to broader principles of justice which are common to all liberal democracies, which are common to courts in other jurisdictions.

Rosie: We're not swashbuckling Don Quixotes wandering the landscape, looking for injustices.

We do justice by working with the law.

But Parliament actually passes laws so when we do interpret what they do, and say you're within the limits of the Constitution or you're not within the limits of the Constitution, we're not trespassing on their role.

We're doing what they've asked us to do by giving us a charter of rights and freedoms.

Is that a controversial role?

Of course.

I mean, nobody who's lost a case ever thinks the court got it right, nobody.

♪♪♪ ♪♪♪ speaker: I don't know if you've been in her office, but it's quite something.

It's like walking into her mind.

Charlotte: I sort of think of it as having, like, fun-house vibes.

I was overwhelmed by all of the art.

Rosie's office is and was a complete contrast to every other Supreme Court judge's office I've been in, and I have been in quite a few.

And their oil paintings and their wooden paneling and their neat piles of papers.

You walk into Rosie's and you think you're in some tchotchke shop in Florida.

Rosie: It's one of the corners that you get for being a senior judge, which means old.

Charlotte: People would go in and they would be completely floored by this.

I was the first time I saw it.

Rosie: He once told me that it was very easy to shop for me because he would go into the store, look for the ugliest thing, and know that I would love it.

Charlotte: It's an unbelievable explosion of pop art, in many cases, frankly, bad taste.

Rosie: Like, I apologize to no one for my taste.

Many would say, "What taste?"

But it's mine.

Andromache: I had standing permission to take any visitor or guest into her office, and it was the one place I would take them, the courtroom and Rosie's office.

Rosie: There are gonna be pictures of my family around.

There are gonna be lots of books, teapots, the kinds of things that make me feel really good about who I am and what I like.

♪♪♪ Christopher: She just welcomes you with open arms and like she's met you and she's known you for your entire life and, you know, it's quite something.

And it wasn't really an interview.

We talked about Broadway the entire time.

speaker: What do you look for in a law clerk?

Rosie: I look for somebody I'm gonna like working with for a year, but mostly, since they're all intelligent, I want people who can think bravely, and what I mean by that is people who can say to me, "I don't agree with that."

Nicholas Martin: When you walk in, she's sitting at her marble desk and you're sitting down on a pink wooden chair and then she conducts the interview and will ask you questions that you don't necessarily expect to get in an interview for the Supreme Court of Canada clerkship.

Gerald: Now, I fancied myself an underground battle rapper slash spoken word poet in my undergrad days at U of T. And sure enough, Justice Abella asked me about it in the interview because she was, you know, fascinated by this little nugget in my application, and I ended up reciting one of my rap verses for her.

♪♪♪ Christopher: When you're a young lawyer, you dissociate the law from people.

But that's not how Justice Abella does it.

She thinks about people.

I learned more in her office than I did in law school.

Charlotte Baigent: Having that opportunity at the very beginning of my career was a really excellent way to set a path for what I hope to accomplish as a lawyer, and I think that she is someone who has made every decision along the way reflecting her values.

And so I think that that's something I will carry with me.

Jocelyn Plant: As sort of every clerk, you know, leaves the court, you have just a better sense of, you know, what the process of justice at that level looks like and that it is, like, quite challenging.

Charlotte: One of the favorite things that any clerk ever said to her was that they would help her create a slab of marble and she would turn it into a statue, and I think that that is a brilliant way to describe the relationship between a clerk and Justice Abella.

♪♪♪ Christopher: She is dedicated to her work until she gets the perfect work product.

Writing, rewriting, starting over, rewriting.

I've never seen someone more passionate about it.

Rosie: These are works in progress.

One is a majority, one is a dissent, but it's the same amount of work for me.

Jacob: You know, I remember when I was a kid, and she had a computer in her office.

She used it to put art on 'cause she had no idea how to work any of that.

So she still does everything by hand, which is remarkable.

Rosie: I swore years ago I would learn how to use a computer but I never got over my fear that I'd lose everything and I wouldn't be able to put it all together again.

I write by hand, first of all, so I edit as I go along and I do it much more slowly.

And then I'm my own worst editor.

I take each draft, and I look at it again, and I edit it, and I edit it, and I re-edit it.

I just keep polishing until I think it's crafted in a way that's clear to understand and that I like reading it.

Charlotte: Certainly, she's got her own style of organization and revisit things and tweak things as she goes and it's quite a beautiful thing to watch, actually.

Caroline Chen: A lot of judges like to throw in very fancy words or very long metaphors that just make it a little bit tedious.

When I read hers, I don't wanna stop reading, and that's a huge thing for a law student where if I'm reading a case decision, I can keep going.

Teagan Markin: She really loves art and literature and you notice that in her writing because she also wants to put in, you know, beautiful turns of phrases and metaphors and so you'll see those in her writing too, and they're really nice when you come across them.

Irving: She writes for the people.

She writes for not the technicians and not the academics, but for ordinary men and women to understand what the law is and what justice is.

Rosie: Well, it can take months, it can take weeks, because the process in this court is that when you write something you think is good enough to put out for scrutiny to your colleagues, then eight magnifying glasses come out.

You know, it's easier if you're writing the dissent because you're not writing for eight other people.

But when you're writing on behalf of the majority, it's a deliberative consultation that is ongoing until the judgment goes out.

Andromache: So Rosie was the master at, kind of, the big picture, the human impact, and the intellectual rigor to get there.

In fact, I remember when I first came to the court, Rosie said to me in Rosie style, "Andromache, it's a family.

It's like having eight spouses.

Imagine having to make important decisions every day with eight spouses, and not only what the decision should be but why."

Adam: That's a very Rosie kind of way, but she'd be able to talk things out and arrive at a better solution.

Andromache: She believed in collegiality.

She would be the first colleague who would get back to you when you circulated draft reasons.

We would get emails from her all hours of the night.

I mean, she had this incredible work ethic.

She believed in people.

Judy Woodruff: What a treasure it is to bring these extraordinary women together.

The Honorable Justice Rosalie Silberman Abella and someone we know very well, the Honorable Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Associate Justice of the United States.

Rosie: The first time I heard somebody say Canada's RBG, it took me by surprise.

Zachary: On a surface level is also the first Jewish female to be on that country's Supreme Court, but I think that's where the comparison ends.

Rosie: I think people mean it, you know, in a really nice way.

I'm honored that they think that I'm--have some resonance with somebody who was really quite a remarkable woman.

I'm very different from her.

Ysabella Hazan: I find that Justice Rosalie Abella really took a lot of sensitivity and care and she's amazing in her own right and can stand on her own, for sure.

Doesn't need to be compared to anyone.

Zachary: Obviously, RGB is, you know, a hero to many people, but that's not my mom.

She was her own person.

She wasn't Canada's RBG.

She is Canada's Rosie Abella.

speaker: Seventeen years as a Supreme Court judge, Rosalie Abella leaves the bench, but she leaves a long legacy.

Rosie: I've left a number of professional homes, each one of them has felt like a home.

It's been a very warm embrace.

The Family Court was, practicing law was.

The Labor Board was, the Law Reform Commission was.

This is special because it's the Supreme Court of Canada which was never in contemplation at any point, including until the day I got appointed here.

But I'm not allowing myself to get sad because I'm looking forward.

But, oh, it was--it was such a great ride.

I loved doing it.

Zachary: I don't think she ever wanted to spend the rest of her life there.

I think she's always been in favor of mandatory retirement or getting off the stage while you still can.

Rosie: Because judging is all about understanding the world around you, and the world changes.

And I like the idea that there are new judges coming in who will bring their perspective, different maybe, but it's their turn.

Rosie: This is not just the last sitting day of the Supreme Court year.

It is also the last sitting day of my Supreme Court career.

I remember how emotional it was when I was sworn in on October 4, 2004, but that was nothing compared to how emotional it is to be sworn out.

Rosie: It was a very proud speech about my generation, how Canada has blossomed in the 50 years since I graduated from law school, and I said, "Okay, we've gotta do this.

We've gotta make this worth listening to."

Rosie: Because I am not only leaving my life on this Court, I am leaving a judicial life that started 45 years ago when Roy McMurtry appointed me to the Family Division of the Provincial Court in 1976.

Rosie: The hardest part was writing about my family.

And that took me two hours.

But I felt good because I wasn't crying, and I always cry when I talk about my family.

But as I wrote it, I wasn't crying.

I said, "Oh, my God, this is gonna be one speech where I don't break down when I talk about my family."

And all of a sudden, I could feel myself welling up and thinking, "Oh, no, I'm not gonna be able to get through this."

Rosie: My life as a lawyer and a judge has been incredibly intellectually fulfilling, but my real life, the life of my heart, rests on the love I feel for my family and the love they give back.

Rosie: And it was thinking about my husband, and then thinking about the kids.

How do you know when you marry at 22, halfway through law school, that 53 years later you will still love the 28-year-old visionary history professor you married?

Or that he will still love you?

How do you know that he will be the most supportive and humane parent your children could have?

Or the most unconditionally encouraging husband?

And how can you know that these two sons you raised together over the last 47 and 44 years would, themselves, turn into such magnificent and brilliant people, husbands, and fathers?

So, to my spectacular husband and sons Jacob and Zachary, and especially their glorious children, our grandchildren and our future, Felix and Maisie, thank you for filling my life with so much love, pride, gratitude, and happiness.

Rosie: And talking about my parents who started it all and, you know, the journey from a Displaced Persons Camp to the Supreme Court of Canada as the first Jewish woman.

It all hit me.

It all hit me.

And I couldn't stop it.

Rosie: My final thoughts are with two people who aren't here but are always with me.

This day, like everything else in my life, would not be possible without my parents.

They were Holocaust survivors whose lives and families were destroyed, but whose optimism and belief in the goodness of people never were.

They brought my sister and me to Canada in 1950 with the highest hopes for a happy life.

They got it, and they gave it to me.

I have been so lucky.

And so, on the eve of my 75th birthday on Canada Day, I say to Canada on their behalf: "Thank you.

Thank you for giving them the life they dreamed of and for giving me a life beyond their wildest dreams."

I am so proud and lucky to be a Canadian.

Thank you.

♪ It's very clear our love is here to stay.

♪♪ Martha: It's such a beautiful, beautiful marriage, and their total and complete love for each other and support for each other, it glows.

You just want to be in their presence.

♪ And the telephone.

♪♪ Jacob: That partnership of my mother and my father is the foundational partnership of our lives.

It is why and how my mother achieved so much and she will still achieve even more, I believe.

But she could not have done it without my father.

Zachary: She was the best friend that any partner could have.

Irving: When I was in the hospital recently, Rosie not only came to visit, she stayed for five weeks.

Rosie: He'd had some issues with his heart, with his kidneys.

He'd spent five and a half weeks in the hospital the summer before with heart failure and almost died three or four times in that period.

Never once complained.

Never once.

Zachary: She would come home from hospital and there would be her grandkids, and she would act like it was just another day at the office for them and for, you know, frankly, for me and my brother.

Irving: She slept in a chair beside the bed, and I couldn't get rid of her.

And she was terrific.

She's my advocate, my partner.

Rosie: He left the hospital at the end of the five and a half weeks on dialysis that was different from when he had gone in.

But his life was saved by the extraordinary medical staff at the UHN and we thought it was gonna be just a question of dealing with a new life on dialysis.

Zachary: She made sure that anything he needed, he would have.

She was the kind of person you would want by your side if you were ever in that situation.

Rosie: Never felt we were losing the battle.

We felt strong, like, I was taking my strength from him.

He was remarkable.

We weren't looking ahead.

We were looking day by day, issue by issue, crisis by crisis, and we were doing it together.

♪♪♪ ♪♪♪ Rosie: He was my life and the kids's life.

He was modest, he was fearless, he was decent, he was honest, he was gentle.

He was so loving.

♪♪♪ Rosie: You don't give up.

You don't stop.

You don't forget.

That's how you honor their memory.

You live the life you know they would have wanted you to have.

It's all you can do.

♪♪♪ ♪♪♪ Rosie: Law sets the beginning of how society functions, but lawyers and judges, they take those bones and they introduce humanity to the possibility of justice, using those laws as the basis, but they're not the end of the story.

Charlotte Gray: Rosie has endless curiosity about the world, and she wants to keep making change, and she loves talking to young lawyers.

She loves talking to young people.

Adam: Good Americans when they die all go to Paris, and good Canadians when they retire all go to Harvard.

♪♪♪ Martha: Many, many places have been after her and saying, "Please come, please come, join us.

Please come teach here.

Please come lecture here."

And I am very excited for Harvard University to host and welcome Justice Rosie Abella.

Rosie: I think probably once I start getting into the academic world I'm joining, it will feel real that I'm no longer a part of the Court.

Zachary: They could have anyone there and they decided that a brilliant Canadian jurist is someone that they would want the future leaders of America to hear from.

And it's very exciting.

Margaret: What the students at Harvard will learn is to think about the great provisions that underlie democracy.

Caroline: So I think it will be really interesting just to hear her perspective on things and have a comparative approach, and when I came here I felt that my Canadian identity became a much larger part of me, so it will be really cool to hear her speak and be, like, "Oh, she's Canadian too."

Rosie: And if one or two students comes away saying, "Ah, you know, that's the way I'm gonna approach access to justice, interesting, I didn't know that's what it was like in Canada, that's a new way of thinking about freedom of expression," one or two, that's fine.

♪♪♪ ♪♪♪ Rosie: I've nothing but an astonishment at the things that I've been able to do in this one life of 75 years.

Joe: She is an example of how a Canadian should excel.

She did it first and naturally at home, but she did it in ways to which the world had to pay attention.

Rosie: You can't argue with the fact that the Canadian Supreme Court is now the go-to court for constitutional courts around the world.

Not the American Supreme Court.

Rosie: So, our jurisprudence, our boldness, our creativity and vision, it's what most post-modern democratic constitutional courts are following.

Charlotte: She wanted the Charter of Rights to work and that was part of a very large legacy.

Paul: When we look at what she's been able to do in the Supreme Court, we shouldn't forget the social consequences of what she did.

Rosie: I will miss the privilege of being able to participate in the decisions that were guiding for the profession.

Andromache: But Rosie's incomparable.

She is always true to her own paths, she's true to her values, she's true to herself.

Jacob: Ten, fifteen years ago, I would not have thought that what my mother had achieved, it would become mainstream and that it would be celebrated.

To me, it's extraordinary.

And I think, to her and to my own family as well.

Zachary: Always proud of what she did for Canada, for the judiciary, for human rights.

Immensely proud of her.

♪♪♪ Rosie: I wanted always just to be really good at what I did, whatever that turned out to be.

And I always give it my all and I gave this my all and I have loved every second of it.

♪♪♪ ♪♪♪ ♪♪♪ ♪♪♪ ♪♪♪ ♪♪♪ ♪♪♪ ♪♪♪ ♪♪♪ ♪♪♪ ♪♪♪

Without Precedent: The Supreme Life of Rosalie Abella is presented by your local public television station.

Distributed nationally by American Public Television