Resistance: They Fought Back

1/27/2025 | 1h 24m 44sVideo has Closed Captions

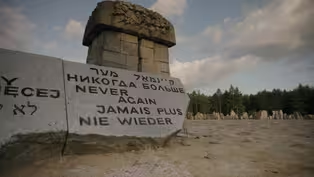

During the Holocaust Jews did not go to their deaths as sheep to the slaughter; they fought back.

People have a myth stuck in their heads that during the Holocaust, Jews went to their deaths “like sheep to the slaughter.” But this is where the real story begins. Jews did not go as sheep to the slaughter. They fought back.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Resistance: They Fought Back

1/27/2025 | 1h 24m 44sVideo has Closed Captions

People have a myth stuck in their heads that during the Holocaust, Jews went to their deaths “like sheep to the slaughter.” But this is where the real story begins. Jews did not go as sheep to the slaughter. They fought back.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Resistance: They Fought Back

Resistance: They Fought Back is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Learn More

"Resistance: They Fought Back" provides a much-needed corrective to the myth of Jewish passivity.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipMan: You know, 40 years, 40 years I've been in the classroom... and there is never a more poignant question that a student asked me about the Holocaust than... "Why didn't the Jews resist the Nazis?"

And there's a moment where you just want to leave it alone... and then there's a moment where you can't let it go.

[Train whistle blowing] [Slow clattering] [Bugle blowing] ♪ [Explosion] [Gunfire] [Soldiers shouting] ♪ Man: After a journey of 10 days, we arrived at Auschwitz on April 11 to a crematorium.

♪ Freund: Marcel Nadjari-- this is a guy who was shipped off from Greece in 1944 all the way to Auschwitz.

♪ [Loud bang] ♪ Man: The Sonderkommando prisoners were slaves, compelled to do anything their masters, the Germans in Auschwitz, tell them to do.

[Shovels clattering] Man as Nadjari: Our unit is called the Special Unit.

I will explain for you the work that the Almighty wanted me to do.

♪ It starts by the people entering naked.

[Water spraying] Greif: The humiliation is a very central factor in the German crime.

He has to be undressed, and he has to be humiliated.

♪ Man as Nadjari: After the room is filled with people, it is locked... [Clang] and they are gassed.

♪ [Gas hissing] Greif: And I have to emphasize 1,000 times the killing always was made by the Germans.

♪ Freund: We're at Crematorium III, which was destroyed by the Nazis as they were leaving in 1945.

What really is the secret of Crematorium III is this is where they discovered Nadjari's letter.

♪ He described in meticulous detail what his daily schedule was, so his letter gives us a perspective on what it is that happened here.

♪ Man: In this horrible world, finding even a pen and a piece of paper without being exposed what they're doing is an incredible bravery, and they probably didn't see hope for their own survival.

They wanted the world to know.

Freund: People have this myth stuck in their heads that the Jews went to their deaths like sheep to the slaughter, but this is where the real story begins.

♪ Man as Nadjari: How could I do this, burn the bodies of my brothers in faith, and why didn't I join them and put an end to it?

But every time, the thirst for revenge stopped me.

[Thump] [Gas hissing] Man: Each prisoner in every squad knew exactly what he was supposed to do and prepared for it.

Different man: May those who made an ocean of blood of my people drown in an ocean of blood.

Woman: Suddenly, the sirens began to wail.

What happened?

A revolution?

An uprising at the crematorium?

♪ Freund: This is where the story begins.

Jews did not go to their death as sheep to the slaughter.

They fought back.

♪ ♪ ♪ [Sobbing] ♪ ♪ Woman as Peltel: Father was calming us, saying, "Don't be scared.

"Even when the Germans come, they are not so bad.

"I remember them from the First World War, and they are quite human, you will see."

For him, it was a shock.

[People shouting] Man: What her father had said was "I know these people.

I know the Germans.

"We fought in the First World War together, and they're basically decent people," and then within the first couple of days, he was pretty badly beaten, and he was so devastated that he was unable after that to leave the house to go out on the street.

♪ Man: We were immediately singled out.

We knew something was coming.

♪ ♪ Man: So this is one of the original walls that confined the Jews into the Warsaw Ghetto, and on Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the Jewish year, in 1940, the Jewish population finds out that it's going to be confined into a ghetto.

Half a million Jews almost forced into this tiny area.

Man: A few hundred people crowd every large, unheated room of a synagogue, every hall of a deserted factory.

A whole family often receives sleeping space for one.

The walls and barbed wire surrounding the ghetto completely cut off the Jews from the outside world.

♪ Patt: These are starvation rations.

There's no way that people can live on this.

♪ Man as Edelman: Children begged everywhere.

6-year-old boys crawled through the walls and barbed wire to obtain food on the other side.

♪ Patt: This was all part of a plan which was going to degrade the Jews, dehumanize them, force them to live in horrible, horrible conditions where you have disease.

[Rats squeaking] The creation of the ghetto was exactly to facilitate the spread of epidemics.

They would bring in film crews into the ghetto as part of their propaganda effort to show this is how Jews live, this is how Jews carry disease and how Jews will ultimately die.

♪ [Digging] ♪ So people often want to know why the Jewish population didn't fight back immediately.

Half a million Jews crowded into the ghetto.

Why didn't they take up arms and fight back against the Germans?

-Collective punishment.

-Collective punishment.

The Jews knew that you can start some resistance.

You can aim a pistol and shoot one person, two people, whatever it is, but the Germans would then arrest 2,000.

♪ Patt: But the truth is, from the very beginning, right, once there crowded into the ghetto, they did resist in the ways that they knew best to do, resistance that was a type of spiritual resistance, resistance that was a way of standing up against the German oppressors.

Feeding the hungry clothing the poor, taking care of orphans.

These were strategies that Jews had used for centuries and which they fell back upon.

♪ Woman: The unarmed resistance is called in Hebrew Amidah.

Amidah is standing, standing up, or in Yiddish, I would say... [Speaks Yiddish] I'm not yielding to the situation.

Whatever you do that is against the situation is resistance.

Whether you sit or lie or crawl or swim or stand up makes absolutely no difference.

It's something done.

Woman as Vladka: Life in the ghetto was a chain of resistance.

There were illegal schools.

there were illegal libraries, choirs, even theaters.

It was an illegal life.

♪ Bauer: The Germans wanted to destroy any kind of Jewish existence, also cultural existence, and so on, so when you educated children in ghettos, if they survived, for them to develop after the War, this was against the German idea, yeah?

Man as Benjamin: I organized a school in my building, and I became the teacher of that school.

I had never prepared for being a teacher, but there were no schools.

All schools were illegal.

Man: And if you always keep in mind that part of what the Germans wanted to do was to kill the body but also to kill the soul, to undermine humanity, the humanity of the individual, and therefore, if you never lost your humanity, then in a very real sense you're helping to defeat the Germans.

♪ Woman as Vladka: Although you see today how the pictures, mostly from Germans, pictures of Jews who were beggars and pitiful, and this is taken because the Germans would like us only to be seen this way.

This was only one part of the ghetto.

It was true there were beggars, but there was another kind of life full of activities and spiritual resistance.

♪ Man as Ringelblum: With a little peace, we may succeed in making sure that not a single fact about Jewish life at this time and place will be kept from the world.

♪ Freund: They were documenting the entire life of the Warsaw Ghetto, and then they buried it, and they buried it because they wanted to make sure it survived.

♪ ♪ It's the equivalent of seeing for the first time the Dead Sea Scrolls.

The difference is this is so close to our own era, and to know that Jews have been documenting and preserved it like a message in a bottle for future generations.

♪ "What we couldn't scream out to the world "we buried in the ground.

"I would like to live to see the moment "when it will be possible to unearth this great treasure "and shout out the truth.

"May this treasure fall into good hands.

"May it survive until better times.

"May it alarm the world to what happened "in the 20th century.

"Now we can die in peace.

"Our mission has been accomplished.

Let history bear witness to that."

♪ Patt: So Warsaw is occupied, and the goal for the Jews is to survive, to live to see another day, to live until the war is gonna be over.

They have no idea that the endpoint of the Germans' occupation is extermination.

♪ ♪ ♪ Man: This is one of the main recreation spots in Kaunas.

It sits up on a hill.

It's windy, it's breezy.

People come here for picnics, to walk their dog.

I've seen wedding ceremonies here, but what people don't know is underneath where we're standing, this is where 50,000 Jews were buried in 14 trenches.

♪ Woman: That -24.

Bauman: This is where the GeoSLAM is going to be.

And--and even if they were to try to memorialize this, they don't know where the trenches are, and that's what... ♪ ♪ Freund: They thought they were going to a labor camp, they were gonna be doing work, and that's what the artifacts tell us.

Passports, watches, personal items, every type of button because everyone thought they were coming to go to work.

Man: Everyone is very smart today.

How didn't they realize?

How didn't they know?

But you never believe.

I mean, you can't believe that you will be mistreated and beaten and humiliated.

You cannot imagine that you will be simply taken... [Gunshots] led to the forest, and killed there.

♪ When we take a look at sites like this-- and we're looking at many Holocaust sites-- and what's important is that survivors have told their story and we believe their stories.

What we're trying to do is bring scientific methodology and scientific tools to verify those stories.

[Ping, ping] ♪ Freund, voice-over: We really are hoping-- and I'm not naive-- we're really hoping that we can diminish genocide when perpetrators know they can never get away with their crime.

♪ [Baby crying] ♪ Man: The most horrific statistic I think of is that only 11% of European Jewish children who were alive in 1939 were still alive in 1945.

♪ My name is Dana Pomerants- Mazurkevich--Mazurkevich.

I'm originally from Lithuania.

I was born in Kovno Ghetto.

My father was a very famous violinist.

My mother and father decided that somehow, by a miracle, somehow they have to smuggle me out of ghetto.

My mother got in touch with Elena Zalinkevicaite.

Was a very beautiful drama theater artist, who had her own 3 children.

My mother, she said, "I have girl who have "beautiful blond hair and has blue eyes.

She's Jewish child.

Could you save her?"

And that Lithuanian woman, having her own children, she said, "Bring that child.

I will take her."

They gave me a big amount of sleeping pills and put me in a sack of potato, and it was one Lithuanian guy.

He took me in some kind of carriage, and then we passed that border, and German soldier was staying there.

Somehow, I probably didn't have enough air, and I started to make that noise.

[Grunting] And that German asked, "What is that?

What is this?"

And that Lithuanian guy, he said, "This is kleine Schweine," little piglet.

Somehow, they let us pass.

It required unbelievable courage, unbelievable, that they could give me away and not knowing if they will survive and not knowing if I will survive.

[Man shouting] I think it was a big, big act of resistance because I will not let to take my child, and my mother had to--oy-- had to give me away.

This is--it--it took so much courage for her to do that.

♪ I have a beautiful daughter Milana.

Sometimes, I think would I be able to do?

I don't know.

♪ [Bells tolling] ♪ ♪ Man: Vilna was called the Jerusalem of Lithuania.

Vilna was probably the most Jewish city in the world.

We consider New York to be very Jewish.

New York's got--15% of the population's Jewish, but Vilna at its peak had 40% of the population was Jewish.

♪ Man: As a child in Vilna, I lived with a sense of living in paradise.

Fishman: It was a great center of Jewish learning.

It was a city of the spirit, and that's why it got the name Jerusalem.

♪ The Germans attacked Vilna on June 22, 1941.

That's almost two years later than when they attacked Warsaw, so the Germans came late, but they acted fast, and the Germans started looting Jewish cultural treasures in Vilna.

In July 1941, they realized that there were just too many Jewish books and papers and documents and treasures in this city.

They couldn't handle it, and that's why they established this slave labor brigade of Jews that would sort the material called the Paper Brigade.

♪ Right here, right behind me, is where the gate to the Vilna Ghetto stood.

The members of the Paper Brigade had to pass through this gate daily.

They had books packed underneath their clothing, under their shirts, under their pants, under their--in their shoes, and they had to pass through body searches of ghetto guards.

If they were found to be carrying books on them-- it didn't matter if you were carrying books or food or anything.

The penalty was the same, death... ♪ and many of those books, once they were smuggled into the ghetto successfully, they brought here to the building that was probably the central address in the Vilna Ghetto, the Vilna Ghetto Library.

Reading was a kind of moral, cultural, spiritual resistance.

"You're not gonna break my humanity.

"I'm a human being, and reading books is "integral to being a human being, and I'm gonna do that."

Bak: It was--absolutely it was a resistance, and it was as indispensable as bread, I would say.

As they say in Hebrew, "Not only on bread can man live."

He needs also something for the spirit.

♪ In the ghetto, where art and writing and poetry were created, where people could express themselves, there was a sense of dignity, and I think this was a very important factor that kept the psyche of the people more or less alive.

♪ ♪ My name is Michael Kovner.

My parents were Abba Kovner and Vitka Kovner-- Kempner-Kovner.

My father wanted to be a painter, and he accepted to the Vilna Academic of Painting.

He was accepted to this, but he couldn't, you know-- the war would come, so he couldn't fulfill this dream, but I think he always was kind of a poet, you know.

My mother, she--she walked on the pavement, which Jewish in Poland after Nazi occupation weren't allowed to walk on the pavement... [Whistle blowing] and she went to the pavement, and then the officer or soldiers, Nazi, came to her, and she-- and he asked her, "You are Jewish?"

And she said yes.

"So why you are going on the pavement?"

She said, "Why not?"

He said, "You are not allowed," and she gave him splash on his face and continued to walk.

So that's her type.

♪ Porat: The youth movement played a role in the life of the youngsters at the time.

They felt belonging.

It wasn't just a place to which you go to be entertained once or twice a week.

You lived your life with the members, you lived through them.

It's a collective identity of being Jewish, and this explains to you the way they handled themselves during the war.

Man as Abba: We had formed our group, starting from a precise ideology.

Our fight was not for self-preservation.

It was not to save myself, to save you, to save a neighbor.

It was to fight the Germans.

♪ Fishman: In half a year, the Jewish population of Vilna went down from 70,000 to 20,000 Jews.

More than 2/3 of the Jews of Vilna were killed in half a year, and that's in 1941, well before there were deportations to the death camps from Warsaw and other cities in Poland.

♪ Man as Abba: One day I was called and told to go to the hospital of the ghetto, that there was a young girl injured who wanted to talk to me and only to me.

From her, I got the first direct evidence about what was happening.

♪ There were 119 women.

They were told to line up.

[Metal clatters] Behind them there were ditches.

♪ The Lithuanians started firing on the whole line of women... [Gunshots] and all the women fell into the ditch... [Gunshot] dead.

♪ This is the burial pit.

It was a burial pit in 1941, and in this forest, both Nazis and their collaborators from Lithuania systematically shot about 100,000 people in these pits.

♪ Man as Abba: One thing is clear to me.

Vilna is not just Vilna.

Ponari is not just an episode.

There is a system, whose inner workings are, for the meantime, hidden from us.

♪ Kovner: My father said, "Nobody can escape.

"The Jewish people cannot escape from this, "so what the Jewish people can do, they can fight for their honor."

That's it.

To fight for the honor.

♪ Man as Abba: They shall not take us like sheep to the slaughter.

All those who were taken away from the ghetto never came back.

♪ Porat: It is a call to the population that was left not to foster illusions.

"Those who went out of the gates of the ghetto will not come back."

Man as Abba: All the roads of the Gestapo lead to Ponari, and Ponari is death.

♪ Porat: He said, "Hitler has a plot.

"He's planning to murder all the Jews of Europe.

If everyone out of the ghetto was killed"... ♪ "and if there is a plan to kill the rest, as well"... ♪ "then there is no other choice left but to resist."

Man as Abba: It is true we are weak and defenseless, but resistance is the only reply.

Brothers, it is better to fall as free fighters than to live by the grace of the murderers.

Resist to the last breath.

♪ ♪ Bauer: Nobody wanted to resist because they said, "If we try to resist, they will kill everyone," and the youth movement said, "They're going to kill everyone anyway," and we must resist.

Woman as Korchak: The soul was enlightened.

The ghetto nightmare dissipated.

Martyrdom, helplessness, and slavery are over, and now the one goal before us is rebellion.

♪ [Speaking Lithuanian] Woman as Vitka: We were not soldiers.

We'd never shot a gun before.

We took a pipe, and another boy got the dynamite.

It was very primitive.

Kovner: My mother, she went with 2 other guys for 3 days outside the ghetto because they have to go very far from the ghetto that the Germans won't know that the Jewish people did it.

That was the most important thing, so she found the best place.

The patrol of the Germans is not there when the train is there at that hour.

She found the best place.

Woman as Vitka: 1:30 in the morning, we planted the bomb.

We took it, and we put it under the rail tracks.

We escaped very quickly.

When the train passed over it at 2:00, it exploded... [Boom] and from far away, we heard the explosion.

♪ Kovner: Heh.

She was the hero of the oldest story.

Like, she was the first one who went outside the ghetto and bombed a German train.

♪ ♪ ♪ Man: One should never believe that Warsaw and Vilna were the only ghettos that rose.

Ghettos large and small rose in resistance.

♪ [Speaking Latvian] [Singing in Yiddish] [Speaking Latvian] ♪ Lensky: If we discuss how the Nazis reacted to resistance, they thought of Jews being so inferior to them that they are unable to resist, that will actually go as the cattle to the slaughter, So we have to understand that when we use this phrase "cattle to the slaughter," we use the Nazi lens.

We look at you through Nazi eyes.

♪ Man: When my mother became a courier, the first task was to move into Grodno.

♪ In Grodno, she was supposed to see what's going on with the Jewish community because there were no connections.

You have to understand there was no telephones.

All telephones were cut.

There was no mail service, there was no Internet.

Woman as Hazan: Each one of us preferred to fall in combat than to be led as sheep to the slaughter.

The movement's leadership sought out girls with a Gentile appearance, who would serve as liaison couriers between the different locations.

This role was unsuitable for boys, who already from the age of 8 days had their Jewishness marked on their flesh.

I volunteered for the role because I'd already gained experience and self-confidence in impersonating a Gentile and going outside the ghetto.

♪ Yaari: They smuggled weapons, guns and grenades and so on.

This was a very dangerous mission.

They also smuggled people out of the ghetto to put them in hiding places.

My mother, she was sent to Grodno.

I must remind you again that she was 19 years old.

Woman as Hazan: I went to the labor bureau in town.

The clerk asked me whether I knew German, and I answered him in poor Yiddish.

For "vos," I said, "was," and so on.

After a few sentences from me, he declared, "You speak German very well.

"You can take a position with us as an interpreter at the Gestapo."

[Telephone rings] Yaari: So when she worked in that office, she managed to steal from the desk all kinds of papers and stamps, and she brought them to Vilna, and they were used to make false identities for--for--for other people, traveling documents and so on.

She was several months, almost half a year, in Grodno.

Her two friends, who were also couriers, Tema Sznajderman, and Lonka Korzybrodska, came to her room.

This was Christmas Eve, and my mother was invited by the Gestapo.

There was one officer who was--I think was in love with her, and he invited her to the Christmas party of the Gestapo, and she said, "I'm sorry, I cannot come because I have two girlfriends," and he said, "Bring them also with you."

He came to pick her up, and the 3 of them, they dressed in the best clothes that they had.

They went on Christmas Eve, December 1941, to this Christmas party, and this Gestapo officer took a picture of the 3 of them.

[Camera flash pops] ♪ June 1942, Lonka Korzybrodska was sent to Warsaw.

She was sent on a mission.

She had to deliver two guns to the underground and information, and she was on the train in the middle between Bialystok and Warsaw, and her luck didn't hold, and she was captured by the Gestapo.

[Steam hissing] So when Lonka did not come back to Bialystok, my mother volunteered to follow her steps and to look for her, so she went on the train from Bialystok to Warsaw, and when the train got to Malkinia, the gendarmes who were on the train told her "We are waiting for you.

Come, come with us."

And why were they waiting for her?

Because Lonka, she was very courageous and very self-assured.

She carried with her the picture of the 3 couriers, and this fell into the hands of the Gestapo.

Woman as Hazan: People in the station looked at me with pitying expressions.

Soldiers asked me, "Little girl, what did you do that they're taking you like this?"

I tried my best to hold my head up so that no one could know what was going on in my heart.

I knew that my chances were gone, that at any moment the Germans were likely to kill me.

♪ Yaari: And after 3 days of severe tortures, broken bones, and a tooth was broken, and after 3 days, they threw her into an isolation cell.

For 6 weeks, she was in darkness all alone... ♪ but she kept her Polish identity.

The Gestapo did not suspect that she's a Jew.

♪ [Clang] [Clatter] ♪ [Dogs barking] ♪ Patt: The Germans were masters of deceit.

They told the Jews they were being sent to work camps in the East, where conditions would be better, but here at the Umschlagplatz, the Jews were loaded onto trains, deported to the death camp of Treblinka.

Man as Edelman: They promised and actually gave 3 kilograms of bread and 1 kilogram of marmalade to everyone who voluntarily registered for deportation.

Do you have any idea what bread meant at that time in the ghetto?

Because if you don't, you will never understand how thousands of people would voluntarily come for the bread and go on to camp at Treblinka.

Woman: There is this diary that someone is meeting a father who is walking toward the Umschlagplatz with his children, and he's asking, "Why are you doing that?

Why are you obeying the Germans' orders?"

And the man says, "Well, they took my wife already.

"I have nothing to give the kids to eat.

"They will starve to death here in the ghetto.

"What can I do?

"I prefer going there and hoping I'll be able to work and provide my children.

So it's really choiceless choices.

♪ [Train whistle blowing] ♪ Steven: The Nazis were single-minded about killing off children with as much cruelty as possible as early as possible.

Berenbaum: Janusz Korczak, the leader of an orphanage who went with his orphans to Treblinka.

He was offered the opportunity to survive.

Korczak was the equivalent of Mr. Rogers.

Non-Jews flocked to hear his radio broadcast.

Are we gonna say that he went like sheep to the slaughter?

Gonna say the teachers that stayed with their students, the doctors that stayed with their patients, the mothers that stayed with their children and didn't abandon them-- did they go like sheep to the slaughter, or did they take care of those they were responsible to unto their last breath?

[Children chattering] Dreifuss: Those children didn't have anybody else to take care of them.

The Jewish children during the Holocaust were maybe the most miserable victims if one can even class within this horrible victimhood, and the fact that somebody is walking with them until the end, even when it's a bitter end, this is something that has its importance.

♪ [Children chattering] ♪ Steven: When it started to go bad, it was moving incredibly fast.

The deportations were so overwhelming that of those 330,000 people who had been in the ghetto, only 60,000 were left.

♪ ♪ Patt: The ghetto is sealed.

Anyone caught leaving or entering is shot on sight.

The walls are porous, and the underground finds ways to sneak fighters in and out to obtain weapons one or two at a time.

♪ Vladka is one of those sent across to the Aryan side to try to find weapons.

Rita: I think she would have said if you asked her directly that she was afraid all the time, but it didn't make a difference.

She always did what was needed to be done.

♪ Woman as Vladka: It was a great event for me when I managed to procure my first revolver, bought from our landlord's nephew for 2,000 zlotys.

Man as Edelman: At the end of December 1942, we received our first transport of weapons from the Polish Home Army.

It was not much.

There were only 10 pistols in the whole transport, but it enabled us to prepare for our first major action.

[Gunfire] ♪ [Indistinct chatter] ♪ Rita: It was the eve of Passover.

That's one of the things I remember her talking about is standing by the window that saw into the ghetto.

She spoke of watching and of wanting to be in there and of feeling like she had been ordered not to.

♪ [Gunshot] Woman as Vladka: Sporadic gunfire erupted in the ghetto.

Powerful detonations made the earth tremble.

The battle had begun.

♪ Schudrich: The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising was the first day of Passover.

Think about it.

They went to fight the Germans with a taste of matzah still in their mouths, and there was matzah made in the ghetto.

Man as Edelman: Battle groups barricaded at the 4 corners of the street opened concentric fire on them.

German dead soon littered the street.

The glorious SS therefore called tanks into action.

The first was burned out by one of our incendiary bottles.

The rest did not approach our positions.

Not a single German left this area alive.

Man: Something has happened beyond our wildest dreams.

The Germans had to flee from the ghetto twice.

The dream of my life has become a reality.

I have lived to see Jewish self-defense in the ghetto in all of its greatness and splendor.

Woman as Vladka: Couriers crisscrossed the ghetto to warn the Jews "Do not allow yourselves to be taken.

"Everyone is to hide in their bunkers.

We must all resist!"

♪ Bauer: The vast majority of the population had no access to arms.

but they identified with the resistance, and they refused to hand themselves over to the Germans.

It was not a passive resistance.

It was an active, unarmed resistance, and that is, after all, a matter of some 55,000 or 60,000 people.

The Jews are hiding.

The Jews are hiding, and the Germans don't succeed in finding Jews.

It's actually unbelievable.

They are entering a house after house.

There are those houses in which hundreds of Jews are living there, and they cannot find even one.

♪ Woman as Vladka: I reflect.

There are so many forms of resistance-- the courageous ghetto fighters firing their pistols, the mother trying to save her baby, the father refusing to allow his son to be separated, the family remaining in hiding under the ghetto.

These, too, are part of the uprising.

These, too, are forms of resistance.

♪ Very soon, the Germans understand that the major problem that they have is of those Jews who are staying in their houses and bunkers despite everything, and this is when the Germans decide to fight the Jews with the weapon of fire, and they start to set the ghetto on fire.

[Fire roaring] ♪ [Speaking Polish] [Wood splintering] ♪ Berenbaum: The Warsaw Ghetto held out longer than the armies of France and Belgium and Netherlands.

What an achievement.

On the other hand, as an action, it was the end.

It was the last act, but as an act of moral resistance to it all, it's a matter of... screaming, shouting, fighting, deciding that I will take the enemy down with me... and not go quietly into the dark night.

♪ [Splashing] ♪ Patt: This stone, taken from the rubble at Mila 18, marks the final resting place of the brave fighters who died here, and it reads, "Here they rest, buried where they fell, to remind us that the whole Earth is their grave."

♪ ♪ [Bells tolling] ♪ [Vehicle driving] ♪ Man as Abba: The Germans' Tactics changed on September 23rd.

At 1 p.m., the ghetto was suddenly surrounded.

They knew we were there.

We had every reason to believe that they'd take out the remaining Jews and then shell with artillery.

We decided to make our way out.

The only way out was through the sewers.

[Splashing] Porat: So that's the end of it.

♪ They went out to the forest with nothing, just the shirt on their back.

That's it.

What do they do?

The forest is rain and snow and wild animals and nothing to eat, and it's a horrible place to live in.

[Rain falling] Woman as Vitka: It was a forest, a forest without Nazis.

We lived there under the sky for two months.

It was raining, and it was cold, but it is what we had in the beginning.

Kovner: It was tough life.

It's very cold, and there was not a lot of food, but they were free people.

They have honor.

♪ [Gunfire] [Train whistle blowing] ♪ Man: Around April 1943, a decision was made to escape.

The decision in the end was a tunnel.

They would take turns.

People who finished their work would come dig.

Some people would pretend to be sick so they could dig all day, and there was a group of diggers, tough people.

[Gunfire] ♪ [People shouting] Man as Jack: When I came out from the tunnel, it was dark.

There was shooting, which I could see lots of flashes of fire.

I could see people being killed.

Woman: This took place on September 26.

It's already cold.

There were drenched.

Pitch black.

Didn't know where to go.

[Thunder] [People shouting] ♪ Kagan: My father-- I remember him telling me that when he first arrived in the camp in the middle of the forest and there was this man on a big white horse with a gun on his shoulder.

My father's like, "Who is that?"

Ha ha ha!

And that was Tuvia Bielski.

Like, just as in the film, right?

In the film, he has a gun slung over his shoulder, and he's a warrior.

My father wrote in his book that when he got to the forests how did he feel, and he said, and here I quote, "I'd come from a camp where thousands of Jewish people "were being killed by the Germans, "and now there were all these fighters with guns.

"I felt very, very proud.

"There was great camaraderie at the camp.

"We were unhappy because so many members "of our families had been massacred, "but we were happy because we were free and we were fighting back."

♪ Cohen: Tuvia Bielski was responsible for saving 1,200 people's lives.

He accepted everybody-- small children, old men and women, solitary women who couldn't fight like my mother, everybody, and Tuvia said he would rather save one Jew than kill 100 Germans.

♪ Kagan: Bielski did something completely different, a completely different philosophy of "We're all Jews.

We need to survive.

That's our resistance."

♪ ♪ Berenbaum: Treblinka had approximately somewhere in the neighborhood of 925,000 Jews being killed.

Some 300 people revolted in Treblinka and escaped.

♪ ♪ In the end, there were less than 100 survivors, but unless they had tried to escape, there would not have been 100 survivors, and then we would have never known anything about Treblinka or at least not from the perspective of the victims.

We would only know the statistics from the perspective of the perpetrators.

Henry: There were 7 rebellions in the death camps.

6 of them were led by Jews, 1 by the Russians, so actually, even if you only consider violent resistance, the Jews look pretty good.

♪ ♪ ♪ [Speaking polish] [Footsteps] ♪ Freund: You can imagine that everyone who came up this way, maybe 180,000 people, thought they were going to showers.

Where they went is the gas chambers.

♪ ♪ [Wind blowing] ♪ ♪ Woman as Raab: And all that built up in me such anger and the feeling of revenge.

I came to the camp with a pair of brown leather boots, which not everybody had, and I said to the group-- we slept together-- "With these boots, "I'm going to escape from Sobibor.

"Don't ask me why.

Don't ask me how, "and maybe it's not-- doesn't even make sense, but I'm going to escape with these boots."

♪ Berenbaum: Alexander Pechersky came with a military background.

He joined with a Jewish prisoner from Poland, who in a very real sense was his liaison with the other prisoners, who didn't quite trust a Soviet POW even if he was Jewish, and they formed a formidable team to plan for how to conquer, how to escape.

♪ Woman as Raab: And that evening, we cried.

We cried very, very much, and everybody said goodbye because we figured in our wildest dreams we didn't think one of us is going to survive, and as I cried myself to sleep, I dozed off, and I saw my mother coming in through the camp, through the main gate, the way I left her.

That's how she looked, and I said, "Mom, you know that we're going to escape tomorrow," and she said, "Yes.

That's why I came."

[Wind blowing] ♪ Berenbaum: They lured Nazi commanders and Nazi officials who were working in the camp into a place where they could be slaughtered one by one.

Woman as Raab: The plan was at 4:00.

The electric wire was cut, the telephone wire was cut.

Everybody has to kill his SS man and his guard at his place of work... [Man screaming] and it started working.

Berenbaum: They then stormed the gates, and then they went into the woods.

[Siren wailing, guns firing] Woman as Raab: This was before decided-- in case anything goes wrong, everybody on his own.

[People shouting] Maybe one will survive and will be able to tell the world.

[Gunfire continues] ♪ [Train clattering] ♪ [Marching footsteps] ♪ Woman as Hazan: When I would go out to the threshold of the block, I could see the smoke rising from the chimneys.

It clouded the skies and choked the air of the entire camp.

I cast glances toward the smoke-shrouded heavens, where it seemed I could see the souls of Jewish children, their mouths gaping to scream.

Yaari: The stories that she told are quite difficult to tell because she faced such atrocities.

Like...I would start crying if I tell this, so... ♪ I cannot tell that really.

♪ [Gunfire] [Explosions] ♪ ♪ [Speaking Hebrew] Berenbaum: Why were the Germans so intent on killing the Jews at that point?

Let's put it very clearly.

The Germans fought two wars, the World War... and the war against the Jews.

When push came to shove, they wanted to succeed in the war against the Jews, even if it took resources away from the World War.

Sawicki: Despite the Nazi regime knows that it is coming to an end, the one group that is supposed to pay the ultimate price will be the Jews.

They're losing, but "What can we do before we lose?

We will kill more Jews."

♪ Berenbaum: When you go to Birkenau, you see that there are 3 railroad tracks that go into the innermost nature of the camp.

Those 3 tracks were built in anticipation of the murder of Hungarian Jews.

Hungarian Jews constituted about 45% of the number of people who were killed in Auschwitz.

That occurred not over 4 years but over 3 months.

♪ There was an entire underground that distributed these passes, that created these passes.

♪ How important was forging?

It was the difference between life and death.

♪ [Steam hisses] [Indistinct chatter] [Train chugging] Yaari: During the transports of Hungarian Jews, which came thousands every day.

Every day, 10,000 people were sent to the gas chambers, and the camp of the women bordered with the train ramp, and when the people from the train were sent to Crematorium Number II, which was 50 meters away from the women's camp.

So all these years that she was in Auschwitz, she was just 50 meters away from 1 of the 4 crematoria in Birkenau.

Woman as Hazan: I suggested digging a trench under the barbed wire fence during the nights through which we would bring young Jewish women into the camp and save them from the crematory ovens.

Now, today, when you go to Birkenau, everything is green and nice, but at that time it was all mud and ditches, so they made some space under the fence.

Woman as Hazan: Our objective was to smuggle into our camp some individuals from within this human mass.

When the girls came through, we were overcome with joy.

Yaari: And they bought in from the line to the gas chambers into the camp about 14 young girls on several occasions They brought them into the camp, and they gave them the dressing of other women who died, and they hid them for some time.

Woman as Hazan: We didn't succeed in bringing many souls into our camp.

There were so few opportunities to do so.

However, the little that we did gave us great satisfaction.

We began to feel a power rising in us, awakening our will to live.

♪ [Crickets chirping] ♪ Man as Nadjari: Now we must disappear from the face of the Earth because we know so much about the unimaginable methods of their abuses and reprisals.

The dramas my eyes have seen are indescribable.

Hundreds of thousands of Jews from Hungary have passed by my eyes, and why didn't I join them and put an end to it?

But every time, the thirst for revenge stopped me.

♪ Man: Nadjari--we don't really know what motivates what he puts into his letter other than he wants to tell the story, he wants to see revenge, and that becomes a more compelling notion than giving up and getting out of the fight.

♪ Man: Each prisoner in every squad knew exactly what he was supposed to do and prepared for it.

My job was to set fire to the crematorium building, where I worked.

Man as Eisenschmidt: The Jews had brought knives to the camp to make kiddush.

Their original purpose was to slice the challah.

They had the words Le-shabbat kodesh, for the Holy Sabbath, engraved on them.

They were long and had white handles.

My job was to make them into bayonets by honing them on all 4 sides.

We produced homemade mines and hand grenades.

We took metal cans of food, filled them with explosives, and put in fuses.

♪ Greif: Between Auschwitz and Birkenau, there was a big munition factory called Union-Metallwerke, which many Jewish prisoners worked.

and one brave, Jewish, young prisoner Róza Robota was 19 years old, had many girlfriends inside that factory, and when she was asked to recruit some of the girls to smuggle out on a daily basis a small amount of gunpowder, she did not hesitate for a second.

My mother was born in Poland.

Her name was Ada, maiden name Neufeld.

She was one of the slave laborers at the factory.

Smuggling itself wasn't easy because they had the body searched on exit from the factory and then on entry to the camp.

My mother told me that she hid it inside her shoe, and once in camp, she would hand it over to someone else, and they bring it to Robota.

Róza Robota would then take it and deliver it to her friend from the Sonderkommando.

♪ Man as Leon: On October 7, 1944, they informed us that the Germans intended to remove the Sonderkommando men from Crematorium IV.

We knew what that meant.

They were going to murder them.

We figured that it was time for action.

[Explosion] Woman: In the distance, we now see billows of smoke burning.

The second crematorium is burning.

Greif: The destruction of Crematoria Number IV, this is a big achievement.

It never functioned anymore again.

Woman: The sirens began to wail, aggravating the commotion.

What happened?

A revolution?

An uprising at the crematorium?

[Gunfire] ♪ Freund: This is perhaps the single most important site for the understanding of Jewish resistance during the Holocaust.

In the most improbable place at Auschwitz, the Sonderkommandos destroyed a combination crematorium and gas chambers.

Henry: It was a defiant and wonderful act that probably saved many thousand lives because they did, in fact, destroy one of the crematoria.

♪ Greif: The uprising came to its tragic end with the killing, murdering of 452 young, Jewish, courageous, brave men.

♪ Yaari: On the night of the 18th of January, the camp was given the order to be evacuated.

[Footsteps] ♪ Woman as Hazan: We marched at a cadence, practically running on winding paths.

We didn't know exactly where they were leading us.

We did understand that we were fleeing from the Russians, heading for Germany.

After the first kilometer, women began to fall.

Whoever found it hard to walk at that quick pace or who stood to rest was shot right away.

[Gunshot] There were moments of despair when I thought of asking those escorting us to kill me, but at those same moments, I would see flashes of rocket barrages in the sky and hear the roar of aircraft, and these inspired me with the will to live.

[Airplane flying] So I'm talking now about the 18th of April.

The Americans was in the process of capturing Leipzig.

My mother stayed behind with the sick prisoners.

The SS are on the way to kill them... ♪ and they decided to escape with the sick people, who could not walk, and then when it became dark, they actually carried them by hand.

This was the night between 18th and 19th of April.

They saved the lives of about 140 prisoners, sick prisoners, and this was my mother's liberation day.

♪ [Cheering] ♪ ♪ "Resistance: They Fought Back" is available with PBS Passport and on Amazon Prime Video.

♪

The Evolution of Armed Resistance

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 1/27/2025 | 2m 54s | Kovner wrote a Manifesto, the first published call for Jews to fight back. (2m 54s)

Jewish Partisans in the Forest

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 1/27/2025 | 3m 26s | Many groups of Jews escaped the ghettos to fight in the forests, denying these areas to Germans. (3m 26s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 1/27/2025 | 1m 46s | Even in Nazi death camps, Jews rebelled. (1m 46s)

Questioning the “sheep to the slaughter” myth…

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 1/27/2025 | 1m 39s | Children were among the most tragic victims in the Holocaust. (1m 39s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 1/27/2025 | 3m 41s | Few Jews had access to weapons in the Warsaw Ghetto, but they resisted nonetheless. (3m 41s)

The Role of Women in the Resistance

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 1/27/2025 | 5m 36s | Women played an outsized role in the Jewish resistance, risking their lives daily. (5m 36s)

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: 1/27/2025 | 30s | During the Holocaust Jews did not go to their deaths as sheep to the slaughter; they fought back. (30s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 1/27/2025 | 5m 2s | The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising was the first armed battle against the Germans. (5m 2s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by: